Editor: Nick Doty

So, you're thinking of adding a new permission prompt to the Web platform? Specification authors and feature designers may find this list of questions useful.

This was inspired by discussions at the W3C Workshop on Permissions and User Consent held last September in San Diego. A full workshop report is available from two days of discussions, covering the challenges of asking for permission, explaining it in context and designing a platform for permissions that are neither intrusive nor fatiguing. That discussion is ongoing (and builds from a workshop on trust and permissions from 2014), but we (PING, the Privacy Interest Group) hope these questions are a starting point for considering new (and existing) permissions right now.

-

Is this feature important for the Web platform?

Specifically, is this feature important functionality that is consistent with the Web's model of privacy, security, accessibility and permissionless innovation? The Web need not be identical to every other software platform, and the distinctive features of the Web -- that software doesn't need to be vetted to operate, that documents and software co-exist, that users can be free from danger and intrusion when visiting a page, that interoperability is available among a wide range of devices and agents -- are essential to its ongoing success.

Some features may not need to be part of the platform at all (and thus not require more complicated user permissions). Some deployed Web features have been subsequently removed by implementers when the invasive potential outweighed the functionality or when most uses were for tracking users rather than intended functionality -- for example, the Battery Status API as described in the Security and Privacy Questionnaire.

-

Does this feature require explicit permission?

Access to data, sensors and capabilities can be designed in a way that permissions are implicit. For example, drag-and-drop doesn't require interrupting the user to confirm whether they want to share a particular file -- instead, the user's action shows that they already want to provide access to a file onto a specific page/function. Can your feature be designed in this way?

For example, we could design a "location picker" rather than a geolocation permission. User agents could implement an input type where the user selects either her current location or a named location that she has saved and often wants to search about.

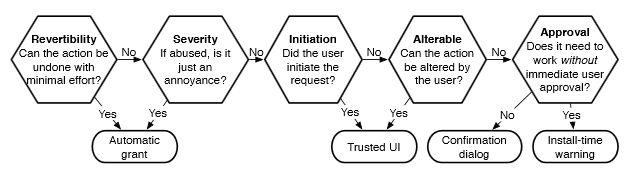

Adrienne Porter Felt's diagram can help determine whether an explicit permission is required. If this feature can be designed to have accountability and mitigations without prior permissions, that can reduce user fatigue without incurring irreparable harm.

-

What capabilities are implicated by the resource, sensor or functionality that you're adding?

Asking users to give permission to a piece of data they don't understand is not helpful. (Acronyms definitely fall into this category.) If the resource provides the site with a capability similar to some other resource or sensor, then there are reasons to consider this the same permission.

Consider also what can be inferred by access to a sensor or piece of personal data that may not be generally obvious. Put yourself in the shoes of a malicious actor to consider the range of possible mis-uses of a feature. Research has shown: that accelerometer data might reveal the contents of typing; that light sensors and microphones might reveal activity on other devices; that photo files often include invisible geolocation metadata.

-

What is the duration and persistence of your permission?

Different user agents may handle persisting permission in different ways. Considering duration and persistence ahead of time is useful, though. Since user attitudes and conditions will change, limited duration or expiration may be important.

If a permission is requested for some future, ongoing or recurring functionality, then additional features are typically necessary for accountability, specifically:

-

transparency: notice for ongoing, background or not-just-in-time actions can be challenging, but ambient notice and asynchronous notice are some options. Without that notice, a user who granted permission in the past and forgot (or someone else granted the permission on their device, or a device had multiple users, or the user previously made a decision in a different context) will not have effective means to update their choices.

-

revocability: easy access to withdraw permission is generally useful but especially important in cases of ongoing permission.

-

-

How will users understand how collected personal data will be used, who has access to it, how long it will be retained and how they can access or delete it?

In the past, specifications have sometimes included a requirement that sites use their own expressive HTML to explain how a capability will be used and their choices regarding it prior to making a browser-mediated permission request. Experience has shown this option to be very frequently ignored by sites (for example, with web sites use of geolocation), even when sites may be required by local laws to get such informed and specific consent.

Workshop attendees concluded that ongoing research on this problem could help explore whether some purpose specification within browser-mediated permission-granting UI could be managed in a way that doesn't violate trust boundaries. (This debate is at least ten years old, but the community is facing many of the same problems today.) For example, iOS provides a "usage description string" from the app developer on dialogs for location and photos permissions.

-

What conditions are necessary for this new permission?

Typically, secure contexts are necessary in order for a user to know who is asking for a permission (otherwise, who would also contain any set of network attackers).

Is this functionality only for top-level browsing contexts, or also for embedded third-party frames?

Does a permission grant background access or only when a tab is active/visible? Background, invisible access requires different affordances for meaningfully explaining and obtaining user permission.

While W3C standardization discussions tend to focus on the design of features, web developers and site owners are more directly involved in asking users for permission on the Web sites they develop, author or control. This is surely a non-exhaustive list, but these may be good principles to keep in mind.

-

Ask for permission in context and just in time.

-

Progressive enhancement: ask for only the permission needed and prepare to gracefully handle cases where a capability is not available.

-

Explain the implications of a permission before prompting the user, in a way that is accessible and localized. Who is asking, what are you asking for, why do you need it?

-

Users can and will change their minds. Don't assume that a permission granted once guarantees permanent access; nor that a permission refused means a user will never choose to accept some functionality. Set expiration of permissions to a reasonable duration, so that users are reminded and have a chance to renew or change their stated preferences.

Image credit: the flowchart above is from Section 8.1 of Adrienne Porter Felt's Ph.D. thesis