The Florida Keys: Dive into History

NOAA Ocean Podcast: Episode 68

In this episode, we're heading to the Florida Keys, the only place in the continental United States with shallow water coral reefs. But these corals are not the only thing that make the Keys special. We're joined by Brenda Altmeier, maritime heritage coordinator for Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary, to tell us the story of the Florida Keys through maritime history to give you just a taste of why this place is unlike anywhere else in the nation.

The rusty remnants of a Totten Beacon (foreground) located near American Shoal lighthouse. Photo credit: M. Lawrence.

Listen here:

Or listen in your favorite podcast player:

Transcript

HOST: This is the NOAA Ocean Podcast, I’m Troy Kitch. In this episode, we’re heading to the Florida Keys, the only place in the continental United States with shallow water coral reefs. But these corals are not the only thing that make the Keys special. We’re joined by Brenda Altmeier, maritime heritage coordinator for Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary, to tell us the story of the Florida Keys through maritime history. It's a story stretching back to the 1500s with trade routes, lighthouses, beacons, shipwrecks, and reefs. And this will give you just a taste of why this place is unlike anywhere else in the nation. Brenda, thank you for talking with us today. Can you tell us a bit about what you do at NOAA?

BRENDA ALTMEIER: I’m the maritime heritage coordinator for Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary, which involves field work associated with documenting, recording, and monitoring historical resources. But we also create and produce educational messages and products about the historical resources and preservation of those resources. It's the look but don't touch: why historical resources are important. They give us the information about our past and the things that shaped our history.

HOST: How long have been with the sanctuary?

Brenda Altmeier, maritime heritage coordinator, Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary.

BRENDA ALTMEIER: I started with the sanctuary in 1993 and I was actually in the education team at that time. Throughout the past 30 years, I've been fortunate to have worked in all aspects of this program, including to help set boundary buoys for our sanctuary preservation areas, repairing coral reefs, installing moorings buoys, updating management plans and programmatic agreements, as well as permitting and documenting shipwrecks. And we do trainings about heritage awareness.

HOST: For those who know nothing about this part of Florida, can you describe it a bit?

BRENDA ALTMEIER: The Florida Keys are a chain of 1,700 islands that extend nearly 200 miles from the mainland Florida. The furthest island is in the Dry Tortugas. These islands are surrounded by teal to deep blue water that's relatively shallow with a mean water depth of about 20 feet. It goes all the way to the deeper reefs that reach about 60 feet before it starts to drop off. So we're almost on a plateau. There are two distinct sides to the islands. We have what we call the ocean side, which is the Atlantic, and then the Gulf of Mexico. And the upper Key, most people refer to it as the Bay side since it's more of a, an inlet bay, doesn't quite open up into the Gulf of Mexico proper.

HOST: And what about the NOAA sanctuary?

BRENDA ALTMEIER: The sanctuary's jurisdiction surrounds nearly the entire island chain — that's 3,800 miles. From that mean high water at the shoreline to 300 feet on the Atlantic side where the water falls off to 300 feet. And then nine miles into the Gulf of Mexico. And we border three national parks, Biscayne National Park in our north, Everglades National Park to our west, and Dry Tortugas National Park at the very tip. And one state park that was established in 1960, which is John Pennekamp Coral Reef State Park. So the sanctuary program down here with the larger Florida Keys was established in 1990 to protect the area from unregulated activities and uses and [to] control damage to the marine environment. Our program required an area to be avoided that surrounded the entire Florida Keys. And what this did was it kept off the large vessels that were trying to use the Gulf Stream, which is like this under underwater river that flows north. And they sometimes come in with the undulation of the Gulf Stream closer to the reef than they should. And we’ve had some major ship groundings that have taken out parking lot sizes of coral reefs in just moments. We also protect coral and historical resources. At one time back in the '50s and '60s, people were chiseling out coral, dynamiting out coral, to sell in tourist shops because it was kind of almost a fad, you know, it was such a unique thing, because it's the only state in the United States where we have shallow water coral reefs. So it was a very big draw for tourists. So that type of activity wasn't regulated. And so the sanctuary helped to put a stop to some of those unregulated activities when we came along. And, of course, that’s why John Pennekamp was established also: to protect that coral reef out to three nautical miles where the state jurisdiction ends.

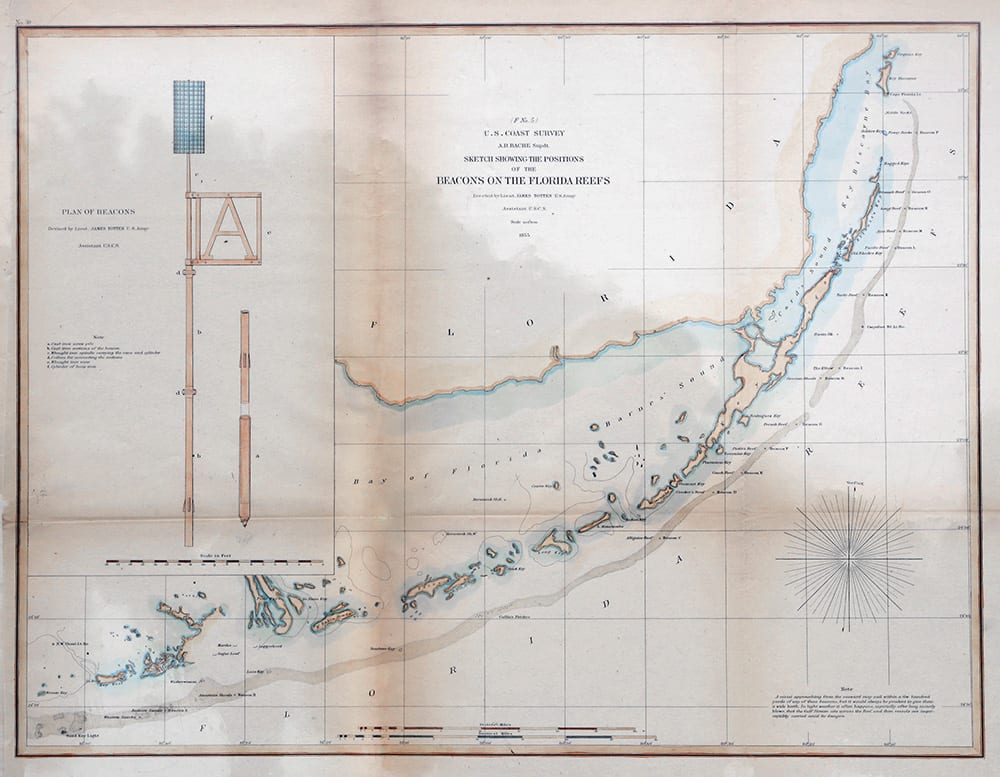

This 1855 map, created by the U.S. Coast Survey, shows beacon locations on Florida Keys' reefs.

HOST: You said one of the things the sanctuary does is to keep large vessels away from the reefs of the Keys, which follow the Gulf Stream around the tip of Florida. Let’s get more into the history of this area as route for mariners.

BRENDA ALTMEIER: So down here in the Florida Keys, we have a major marine highway and it's been a highway for a very long time, beginning in 1513 when Ponce de Leon, the Spanish explorer, first laid eyes on the Keys. The increasing traffic continued over the centuries to follow. They've come up along the island set using the Gulf Stream, which is an underground current that flows north. So when these voyages of these Spanish explorers came from Central and South America, they came up by Cuba and then followed this, what they called the New Bahama Channel, which is the Straits of Florida that would travel up along the Keys. And it was noted very early on that this underwater river helped to propel those vessels quicker in their northward movement. Of course, that's not something you want to fight coming south because then it will push you back, but they recognize that this was a very important waterway to help them save time and effort when they're moving northward. The challenges down here include weather conditions. We've had a lot of ship groundings in this area because there was lacking navigation aids. The waters are very tricky. There's shallow coral reefs. They're shoaling sand and it's not a water that you can guess where the deep spots are. You know, in some areas of the world, the darker spots mean that it's deep water, but down here that can indicate a shallow coral reef right up ahead of your vessel. So it's very tricky. The large ships that sailed back then were heavy. They were large. They required sail, a lot of canvas, and they depended on the wind. So depending on what direction the wind was blowing, they may or may not get the movement they needed or they may not be able to tack in the right direction to keep themselves from going afoul on a reef. So it was a very tricky time and to man all those sails were needed a lot of people on those vessels as well. And sometimes sickness went through the whole boat because you're living in and amongst each other. So there was a lot of complications. The instrumentation wasn't great. You know, it's not like nowadays where there's, you know, Garmin GPS, they didn't have charts, they lacked instrumentation and everything. So it was a considerable difficult time for early mariners.

HOST: With a lot of shipwrecks.

BRENDA ALTMEIER: Hundreds, yeah. We have hundreds of shipwrecks throughout the Florida Keys throughout many different periods of time from that early exploration in the 1600s. There was two large vessel groundings that occurred as a result of hurricanes back in the 1600s with the Atocha and Margarita and that fleet and then the 1733 fleet that were heading back to Spain. They left Havana Harbor July 13, 1733, and ended up in a hurricane and 13 vessels were strewn along the Florida Keys reef line. During the American period in the 18th and 19th century when the United States was rapidly growing and relying on shipping for transportation of people and goods, the route along the Keys was that major highway that was a conduit for all these vessels coming from ports of the interior. Goods that were being shipped from further north and being sent through Louisiana out to the Eastern Seaboard. They all had to travel along this dangerous shipping route on the Florida Keys.

HOST: So something had to change to make these shipping journeys safer.

BRENDA ALTMEIER: The Safe Navigation was a priority of the Lighthouse Act that was passed in 1789. And this established the aids to navigation to regulate and encourage trade and commerce in the world. So that was HR 12, which was signed on August 7, 1789, by President George Washington. The Coast Survey was established in 1807 and was directed to create accurate charts of all United States coast and waters. That was one of our country's priorities that we had to get this right because that's the main way things got transported.

HOST: As a side note to our listeners, the Survey of the Coast was the official name of the office established by President Thomas Jefferson back in 1807. And — little known fact — this was the first scientific agency of the U.S. government. And it was the predecessor of today’s Coast Survey office, which is part of NOAA’s National Ocean Service. So NOAA traces its roots all the way back to 1807! Brenda, can you talk a bit about the work coast survey teams did in the Keys back in the day?

BRENDA ALTMEIER: The Coast Survey spent nearly 40 years in the Keys assisting the Lighthouse Service to map and mark the reefs. It was a long time, it was very tedious work. There's a lot of shallow areas, a lot of reefs that come up out of nowhere. The justification reached a head in 1848. They used the records that were associated with ships that were lost between 1844 and 1848. There were 174 vessels that wrecked on the reef during that time period and the losses were in the millions. So you had the merchant screaming, you had the insurance company screaming, you have the government trying to figure this out, we need to do something that makes this safer, because these goods need to make it to their end destination and commerce needs to continue.

HOST: So what did they do?

Brend Altmeier investigates the iron frame used to mount a letter onto the beacon at Eastern Sambo.

BRENDA ALTMEIER: The first lighthouses were established in 1825 at what we call like the head of the Keys, which is Cape Florida. It's a very tip of mainland Florida on that eastern side. And then, in the Dry Tortugas, which kind of is the both end headpins, I guess of the challenging area. So in 1853, there was a series of unlit beacons that were erected because we were waiting for money appropriations to build offshore lighthouses. They were still trying to figure out how to do this.

HOST: What were these beacons like?

BRENDA ALTMEIER: These unlit beacons were just a pole, pile pole, that were installed into the seafloor. And they sent down Lieutenant James B. Totten with the United States Army, who was an assistant now to the Coast Survey to construct these pile poles. They were innovative at the time because they were so cost effective and fairly easy to install. And they saved a lot of lives. So it was pretty important. They were 30 to 40 feet tall. And at the time they were topped with a single barrel. It was painted black, had some red and white on there as well. In the vein of this pole was a letter and it went from A to P. And there was 15 of these in all.

HOST: From the photos I’ve seen on the Florida Keys Sanctuary website, these original beacons have decayed and collapsed over time, but they’re still there. For our listeners, check the show notes for this episode for links to the Sanctuary website where you can see 3D images of the remains of the Totten Beacons that you can actually move around to view from different angles. It’s a view that only divers can see that you can see right from your living room — it's pretty cool — and Brenda was part of the team that made this possible.

BRENDA ALTMEIER: We did a project in 2014 to document these unlit beacons. We thought that this was an important part of our history that needed to be marked you know the lighthouse is prominent they're there and some of these beacons exist right next to the lighthouse so we got a team together … and we took a week and the grant provided us the funding to put this all, together. So we were able to document five of the 15, which is a smaller amount of them, but some of them we couldn't find. But what we found was this, the remains of the, you know, this four foot by four foot frame, if you will, with the letter on the inside. And, you know, it just is a mark in our history how our area was a pivotal point, you know, for this marine traffic to make its way past here or without getting caught up in the reefs. And the ingenuity of the time, you know, the many people that were part of trying to figure out what the best thing to do to make them safer. So these piles, these beacons, are important in our history.

HOST: It’s like a museum in the ocean.

BRENDA ALTMEIER: A lot of our economy is based on tourism and the tourism is heavily driven by being in the water, going in the water, diving, snorkeling, fishing of course, as well. But you know to visitors who come down and can see something like that underwater, it's a feeling like nothing else. There's plenty of historic artifacts that had been brought up in the 50s and 60s by treasure hunters that are left along the highway and I don't see anybody stopping at them. I don't see anybody stopping to look and really appreciate that that was from a tall ship that sailed maybe in the 17th century, people that were transported over here that now started our population. There's no love for those artifacts. But when you go underwater, you get a different feeling about it. You see them in situ, you can appreciate the event, what happened, why they're here, a lot more than you can if they're brought back and shoved in a museum or put up along the roadside.

HOST: And along with the remnants of the Totten Beacons, what other aids to navigation mark the shallow reefs in the sanctuary?

BRENDA ALTMEIER: We have five offshore lighthouses that are in our Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary. In 2012, the Coast Guard de-assessed these lighthouses from their property, and they were no longer needed because they installed newer poles, almost like the historical poles that were installed in the 1850s next to the lighthouse, and took the place of the lighthouse, and since they could no longer maintain them, they're very expensive to maintain. As you can imagine, being as old as they are and with the personnel that had to go in and change lights and make sure that they had batteries to operate these lights. So it became just too cost prohibitive to keep them up. So the new lights have a brighter light and they’re next to or close to the original light house structures. So now we have in some of these locations, we have a series of three, we have the 1850s series beacons from Totten. We have the light houses that were installed, and then we have the new beacons. Of these five light houses, the new beacon is what is used today.

HOST: So the original beacons are now part of history, but there are some new, smaller beacons with brighter lights installed by the U.S. Coast Guard. And the lighthouses are no longer in use, then?

BRENDA ALTMEIER: The lighthouses are no longer lit. They've been deactivated and sold to private hands. One of them was deeded to a local group called the Friends of the Pool. Their desire is to fix this one lighthouse up so that it's kind of the way it was or way it would have looked had it been properly conserved, and allow visitation to the internal workings of the lighthouse and really celebrate history that way.

HOST: Brenda, you’ve lived in the Keys for more than 30 years. You experienced the decommissioning of the lighthouses, as four of the five of them in the Keys were sold off to private owners and the fifth, Alligator Reef lighthouse, is now being preserved by the local community group we mentioned, Friends of the Pool. And you’re witnessing the installation of new, much smaller, modern beacons. What was it like to witness all of this change?

BRENDA ALTMEIER: Navigation has changed over the many years. So most people use a Garmin. They might not even do dead reckoning, they don't use paper charts anymore. So because of navigation changing, the Coast Guard felt that most people no longer need to have these tall beacons, you know, 100 and some feet tall, to identify where they're going because everybody's using navigation instruments. So back in 2012 when the Coast Guard declared that they were de-assessing this property because they no longer needed it and it was becoming too costly for them to maintain these lighthouses, then the General Services Administration took over, took many years to all the way up until 2021-22 to find appropriate new owners for them. So here's where we're at. I think the Friends of the Pool got their deed in 2021 or 22. And yeah, it was quite an eerie sound and a heart-hurtful sound when, you know, I remember distinctly, I was on the boat, the RV Agassi, one of our boats going out to do work in the field. And the Coast Guard does what they call a PAN-PAN over the radio to alert mariners that something may be an obstruction, it might be a change in navigation, it might be a marker down. And I heard the PAN-PAN come over about Alligator Reef Lighthouse was permanently extinguished. Crazy. I mean, it was crazy to hear that because, you know, all the years that I've been here and to know that they were here for hundreds of years before me and to think that there's this delineation, this mark that I'm seeing here in history where it's like, that's it. They're no longer lit. From here forward, we're moving into this new era.

HOST: Thank you for joining us today. That was Brenda Altmeier, maritime heritage coordinator for Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary. A reminder to check our show notes for links to the Florida Keys Sanctuary website, there are more amazing stories, 3D imagery, and just so much to explore about this unique place. Thanks for listening to the NOAA Ocean podcast. We’ll be back soon with a new episode.

From corals to coastal science, connect with ocean experts to explore questions about the ocean environment.

Social