Abstract

Histone proteins contain epigenetic information that is encoded both in the relative abundance of core histones and variants and particularly in the post-translational modification of these proteins. We determined the presence of such variants and covalent modifications in seven tissue types of the anuran Xenopus laevis, including oocyte, egg, sperm, early embryo equivalent (pronuclei incubated in egg extract), S3 neurula cells, A6 kidney cells, and erythrocytes. We first developed a new robust method for isolating the stored, predeposition histones from oocytes and eggs via chromatography on heparin-Sepharose, whereas we isolated chromatinized histones via conventional acid extraction. We identified two previously unknown H1 isoforms (H1fx and H1B.Sp) present on sperm chromatin. We immunoblotted this global collection of histones with many specific post-translational modification antibodies, including antibodies against methylated histone H3 on Lys4, Lys9, Lys27, Lys79, Arg2, Arg17, and Arg26; methylated histone H4 on Lys20; methylated H2A and H4 on Arg3; acetylated H4 on Lys5, Lys8, Lys12, and Lys16 and H3 on Lys9 and Lys14; and phosphorylated H3 on Ser10 and H2A/H4 on Ser1. Furthermore, we subjected a subset of these histones to two-dimensional gel analysis and subsequent immunoblotting and mass spectrometry to determine the global remodeling of histone modifications that occurs as development proceeds. Overall, our observations suggest that each metazoan cell type may have a unique histone modification signature correlated with its differentiation status.

The fundamental unit of chromatin is the nucleosome, composed of DNA wrapped around an octamer of two copies of each of the four core histones. The histone proteins are subject to a wide range of post-translational modifications, including, but not limited to, acetylation, phosphorylation, methylation, and ubiquitylation. These modifications are hypothesized to constitute a “histone code” that promotes or inhibits all of the chromosomal transactions that occur in the cell (1). Variant histone proteins, found in a subset of nucleosomes, provide additional complexity to the code (2, 3). The modifications and variants at a particular chromosomal locus putatively function by recruiting or repelling, in a multivalent fashion, specific activators or repressors, chromatin remodelers, and other proteins (4, 5).

Post-translational covalent histone modifications have been identified in many organisms with a variety of techniques, including chromatography and spectroscopy, mass spectrometry (6), and specific antibody detection (7, 8). Many of the modifications have been strongly correlated with specific cellular functions, including transcriptional activation (e.g. H3K4 methylation, H3 and H4 lysine acetylation, and H2B ubiquitylation) (9), transcriptional elongation (H3K36 methylation), transcriptional repression (H3K9 methylation, H3K27 methylation, H4K20 methylation, and H2A ubiquitylation) (10), and cell cycle progression (H4K20 monomethylation, H2A/H4S1 phosphorylation) (11, 12).

Dynamic changes in these modifications can occur on individual gene loci and genome-wide but in a particular cell type may be strongly correlated with the overall genetic activity of that cell. Many studies have recently observed a few histone modifications in a genome-wide view using new chromatin immunoprecipitation techniques coupled in-line with high-throughput DNA sequencing to determine the specific genomic location of those modifications (13). These studies have demonstrated how different the histone variant and modification profile is at different genomic loci within the same cell type.

The maturing Xenopus oocyte and laid egg have an accumulated store of nonchromatinized, predeposition histones complexed with chaperones, including nucleoplasmin (H2A and H2B) and N1 (H3 and H4) (14, 15). H4 has been shown in many species, including Xenopus, to be acetylated on Lys5 and Lys12 prior to deposition during S-phase (16); the role of these modifications is still unknown. The store of histones in the egg has been hypothesized to be required for the rapid cell cycles in the developing frog prior to the midblastula transition (17). At the midblastula transition, zygotic transcription starts, and the cell cycles slow down with the acquisition of gap phases and a longer S-phase (18). Early evidence suggested that there is an adequate store of histones in the egg to complete the exponential increase in chromatin during the 12 cell cycles prior to the midblastula transition (19–21). However, histone transcripts do exist in the egg and early embryo (22), and histone translation does occur (23), suggesting that this protein store may not be the entire complement of histones that is used. Furthermore, other than the preexisting H4 acetylation (24), no other modifications have been demonstrated on the stored histones in Xenopus eggs. We do note that H3K9me was observed on pre-deposited histones in cultured mammalian cells (25), suggesting that there are likely to be a variety of modifications present on histones prior to chromatin assembly that may play a role in potentiating an epigenetic state.

Considering the range of different histone variants and modifications that have been discovered, we hypothesized that different cell types may have their own global index of histone modification enrichments in total. We also were interested in analyzing the histone modification and variant transitions during remodeling of the early embryo. Therefore, we isolated histones from seven distinct cell types of the frog Xenopus laevis, including stored oocyte, stored egg, sperm, early embryo equivalent (pronuclei incubated in egg extract), S3 tissue culture cells (derived from a neurula explant), A6 tissue culture cells (derived from an adult kidney), and the nucleated, terminally differentiated, and completely silenced erythrocytes of the adult frog (26). We subjected these histone proteins to a variety of analyses, including immunoblotting with specific post-translational modification antibodies (this paper) and high resolution mass spectrometry (see accompanying article (45)). The isolation procedure for the stored egg histones described in the literature utilized a guanidine/alcohol precipitation step that only had a historical basis for its application (20, 27, 28); furthermore, there was no evidence presented that the entire complement of histones was actually isolated. Therefore, we developed a new approach for the stored histone isolation (in both oocytes and eggs) that we present here. We finally conclude with a summary of the modification index and the transitions that occur from oocyte, egg, and sperm through the early embryo.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Extract Preparation—Xenopus interphase egg extract was prepared as described (29). Clarified egg extract was prepared from low speed supernatant that was spun in an SW-55 rotor at 50,000 rpm × 2 h. The clarified middle layer was removed and respun for 30 min, and glycerol was added to 5%, aliquoted, and flash frozen. Xenopus oocyte extracts were prepared from freshly dissected ovaries by disrupting the follicular layer with a 3-h digestion with Dispase II (40 mg/100 ml) at room temperature, followed by a 1-h digestion with collagenase (50 mg/100 ml), all in 1× Merriam's buffer (10 mm Hepes, pH 7.8, 88 mm NaCl, 3.3 mm Ca(NO3)2, 1 mm KCl, 0.41 mm CaCl2, and 0.82 mm MgSO4). The defolliculated oocytes were then washed extensively with 1× Merriam's containing 200 mm sucrose and 1 mm DTT,2 and the later staged oocytes settled to the bottom (the less dense stage I and II oocytes were mostly lost during the preparation). The oocytes were settled in 13 × 51-mm Beckman ultracentrifuge tubes, and excess buffer was removed. They were then spin-crushed at 35,000 rpm (150,000 × g) for 40 min in an SW-55 rotor. The middle layer was removed with a pipette and respun for 30 min. The middle layer was again removed, glycerol was added to 5% final, and the extract was aliquoted and flash frozen in liquid nitrogen.

Pronuclei (Early Embryo Equivalent) Preparation and Chromatin Isolation—Pronuclei were prepared by swelling 12,000/μl demembranated sperm chromatin in 2 ml of interphase egg extract until mid-to-late S-phase, (determined by 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole staining and microscopy showing the appearance of rounded, large, membranated nuclei with recondensing chromatin). The suspension was raised to 10 ml total with ELB-CIB buffer (10 mm Hepes, pH 7.8, 250 mm sucrose, 2.5 mm MgCl2, 50 mm KCl, 1 mm DTT, 1 mm EDTA, 1 mm spermidine, 1 mm spermine, 0.1% Triton X-100, 10 mm sodium butyrate, 1× phosphatase inhibitors, and 1× protease inhibitors), mixed, and incubated on ice for 10 min. The chromatin was isolated via centrifugation at 4000 rpm for 5 min through a 1-ml sucrose cushion of ELB-CIB with 0.5 m sucrose underlayered in the tube. The pellet was washed once with ELB-CIB plus 250 mm KCl.

Erythrocyte Preparation—Five frogs were sacrificed and bled into an ice-cold solution of 150 mm NaCl, 10 mm Hepes, pH 7.9, and 5 mm EDTA (30). The blood-containing suspension was filtered through 10 layers of cheesecloth and centrifuged at 4500 rpm for 10 min. The pellet was washed twice with Buffer X (10 mm Hepes, pH 7.8, 80 mm KCl, 15 mm NaCl, 5 mm MgCl2,1 mm EDTA) with added 0.2 m sucrose and protease inhibitors (Roche Complete) and spun at 4000 rpm for 10 min in a tabletop swinging bucket centrifuge. The pellet was then resuspended in a low salt/hypotonic buffer containing 10 mm Hepes, pH 7.9, 5 mm MgCl2, 10 mm KCl, 1 mm DTT, 0.5% Nonidet P-40, and 10 mm sodium butyrate, phosphatase inhibitors, and protease inhibitors. The suspension was pipeted up and down on ice for 10 min and then layered over 2 ml of Buffer X with 0.5 m sucrose and 0.03% bovine serum albumin. This was spun at 4000 rpm for 10 min in a tabletop swinging bucket centrifuge and repeated over Buffer X with 1 m sucrose; white nuclei remain (the red hemoglobin was in the supernatant at this point, indicating complete lysis of the cells). The erythrocyte nuclei were spun at 14,000 rpm × 1 min, and the supernatant was removed and resuspended in Buffer X plus 0.5 m sucrose and 0.3% bovine serum albumin, protease inhibitors, 10 mm sodium butyrate, and 1 mm DTT. The nuclei were counted, aliquoted, and flash frozen.

Tissue Culture—Xenopus S3 and A6 tissue culture cells were grown in 60% Liebowitz L15 medium with 10% FBS at room temperature in a laboratory drawer according to standard tissue culture techniques.

Histone Isolation—Histones from sperm chromatin, S3 and A6 tissue culture cells, and erythrocyte chromatin were collected and isolated in the presence of 10 mm sodium butyrate and acid-extracted as described (31). Pronuclei were isolated from egg extract as described above, washed with 300 mm NaCl, and acid-extracted.

Stored histones from oocyte and egg extracts were purified by chromatography on heparin-Sepharose. 1 g of heparin-Sepharose CL-6B dry resin (catalog number 17-0467-01; GE Healthcare) was swollen and washed in Buffer H (40 mm Hepes, pH 7.8, 10% glycerol, 1 mm DTT, and 1 mm EDTA). 3 ml of swollen resin was collected, and 3 ml of clarified egg or oocyte extract, containing fresh 10 mm sodium butyrate, phosphatase inhibitor mixtures, and protease inhibitor mixture, was applied in “batch” form. 20 ml of additional Buffer H was added. The tube containing the resin and extract was rotated for 2 h at 4 °C, and then the suspension was spun down at 4000 rpm for 4 min. The supernatant (flow-through) was collected, and then the resin was washed 4 times with 50 ml of buffer H with inhibitors, followed by transfer to a disposable plastic column. The resin was then washed with 30 ml of buffer H plus 0.1 m NaCl and then 30 ml of buffer H plus 0.5 m NaCl. The histones were then eluted from the heparin-Sepharose with 15 ml of buffer H plus 2 m NaCl. The eluent was diluted to 40 ml with H2O, and 10 ml of 100% trichloroacetic acid was added to 25% final concentration (w/v), and the tube was incubated on ice for 30 min. The suspension of precipitated histones was spun in an SS34 rotor at 10,000 rpm for 10 min, and the supernatant was discarded. The precipitate was washed twice with 100% ice-cold acetone and then briefly air-dried. The histones were dissolved in 1 ml of H2O and used for subsequent analysis.

Immunoblotting—Histones were run on homemade 17% (37.5:1 acrylamide/bis) 0.75-mm-thick SDS-polyacrylamide gels, and transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride (Millipore) using 1× NuPAGE transfer buffer (Invitrogen). Membranes were stained using Direct Blue 71 stain to ensure proper transfer; any membranes with inadequate or uneven transfer were discarded. Membranes were blocked in 1% ECL Advance blocking agent (GE Healthcare) and blotted with antibodies from Millipore and Abcam (listed below). Secondary horseradish peroxidase-coupled antibodies were applied and then visualized using ECL Advance, with images captured using the Fuji LAS-3000 digital system. Images were incrementally exposed until CCD saturation, and the exposure before saturation was used for analysis. Images were aligned with molecular weight markers by simultaneous capture of the lit membrane and subsequently cropped, and levels were adjusted for contrast in Adobe Photoshop; no exposed bands were eliminated upon adjustment. One immunoblot was performed for each modification.

The antibodies used from Millipore (formerly Upstate) were as follows: H2A (07-146), H2A.Z (07-594), H4 (07-108), H3K4me1 (07-436), H3K4me2 (05-684), H3K4me3 (07-473), H3K9me1 (07-450), H3K9me2 (07-212), H3K9me3 (07-523), H3K27me1 (07-448), H3K27me2 (07-322), H3K27me3 (05-851), H3K79me2 (07-366), H4K79me2 (05-734), H4K20me1 (07-440), H4K20me2 (07-747), H4K20me3 (07-463), H4K5ac (06-759), H4K8ac (06-760), H4K12ac (06-761), H4K16ac (06-762), H3ac (06-599), H3K9ac (06-342), H3K14ac (06-911), H4R3me2a (07-213), H4cit3 (07-596), H3R2me2a (05-808), H3R26me2a (07-215), H2A/H4S1ph (07-179), and H3S10ph (05-817). The antibodies from Abcam were H3 (ab1791) and H4R3me2s (ab5823).

Two-dimensional Gel Analysis—Purified histones were run on a two-dimensional Triton-acid urea/SDS gel and transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride as described (31).

Mass Spectrometry Analysis of Gel Slices—Coomassie-stained gel bands of interest were excised and digested with trypsin, as previously described (32). Following enzymatic digestion, peptides were extracted, dried down completely, and stored at -35 °C prior to analysis. Peptides were resuspended in 0.1% acetic acid and loaded onto fused silica microcapillary pre-columns (360 × 75 μm, outer diameter × inner diameter; Polymicro Technologies, Phoenix, AZ) packed with 8–10 cm of irregular 5–20 μm C18 beads (YMC, Kyoto, Japan). The precolumn was washed with 0.1% acetic acid for 15 min at 500 p.s.i. and then connected via a Teflon sleeve (0.060 × 0.012 inch, outer diameter × inner diameter; Zeus Industrial Products, Orangeburg, SC) to a microcapillary analytical column (360 × 50 μm, outer diameter × inner diameter) packed with 6–8 cm of regular 5 μm C18 beads and equipped with a laser-pulled (P-2000; Sutter Instruments, Novato, CA) electrospray emitter tip (2–5 μm in diameter).

Peptides were gradient-eluted into a Thermo Electron LTQ-Orbitrap utilizing an Agilent 1100 series HPLC (Palo Alto, CA) with a gradient of 0–60% B in 60 min, 60–100% B in 3 min, and held at 100% B for 4 min (A = 0.1% acetic acid; B = 70% aceto-nitrile in 0.1% acetic acid). Mass spectrometry data were searched against a data base of Xenopus and human proteins (for detection of contamination and for completeness, since not all Xenopus protein sequences are archived) from the nonredundant data base from NCBI utilizing the Open Mass Spectrometry Search Algorithm. collisionally associated dissociation spectra of peptides from proteins receiving at least two search hits were manually inspected and verified.

RESULTS

We initially wanted to examine the stored histones in the Xenopus egg and oocyte, known to be complexed with the chaperones nucleoplasmin and N1. The published procedure of guanidine/alcohol precipitation (20) did not lead to an appreciable enrichment of histones in our hands (data not shown); nor did acidifying the extract and collecting the remaining soluble material (data not shown). Furthermore, immunoprecipitation of the chaperone nucleoplasmin did not enrich a significant mass of histones (data not shown), consistent with published reports (33). Conventional ion exchange chromatography resolves the histones into a variety of subpopulations (15), which would complicate subsequent analysis. Therefore, we applied crude oocyte and egg extracts to heparin-Sepharose (previously utilized to separate histones (34)), a highly negatively charged matrix that mimics the electrostatics of DNA, the native partner of histones (Fig. 1a shows a schematic of isolation of histones from a variety of native sources). Fig. 1b shows the highly enriched elution of all four core histones from the heparin-Sepharose in 2 m NaCl (Fig. 1 only shows purified egg histones, but oocyte histones behaved identically). These histones are nonchromatinized, predeposition histones. In Fig. 1c, Western blotting with antibodies against H2A, H2B, H3, and H4 show that the histone population is largely retained on the resin until complete elution with high salt, since no histones remained on the resin. Some H2B did not bind to the heparin Sepharose, as seen in Fig. 1c. Also note that the antibodies against histones H2A and especially H4 did not recognize any protein in the crude extract but did recognize the purified protein. We have consistently observed this lack of H4 antibody binding in crude extracts.3 The eluted histones were precipitated and redissolved into water and used for subsequent analysis. Based on the HPLC traces from the purified histones, equivalent amounts of all four core histones were present in the oocyte and egg heparin fractions (Fig. 1 in Ref. 45).

FIGURE 1.

Isolation of histones from Xenopus tissue and remodeling in egg extract. a, schematic diagram of different cell types used in this study. We pooled oocytes from stages II–VI and separately pooled laid eggs. We subsequently prepared soluble extract and then applied the extract to heparin-Sepharose to isolate purified histones. b, Coomassie-stained gel showing the applied and eluted fractions of proteins from egg extract applied to heparin-Sepharose. The location of the core histones is indicated. Note that Xenopus egg and early embryo histones H2A, H2B, and H3 tend to migrate together in a single band on a high percentage SDS-polyacrylamide gel. c, Western blot of the fractions from the heparin-Sepharose column, showing the retention and specific elution of histones H2A, H2B, H3, and H4. d, Coomassie-stained gel of acid-extracted histones from sperm chromatin (first lane) and sperm chromatin assembled in egg extract (so-called pronuclei chromatin) (second lane). The location of the core histones is noted. Also indicated are the identification of proteins in gel slices from each lane, as determined by mass spectrometry, including the sperm-specific histone H1fx as well as the sperm-specific basic protein 4. Proteins that are acid-soluble and assembled on chromatin during pronucleus production in egg extract were identified by mass spectrometry. Those protein names are listed below the gel. e, Coomassie-stained gel of acid-extracted histones from erythrocyte chromatin (first lane) and erythrocyte chromatin assembled in egg extract (second lane). The location of the core histones is noted, as is the putative location of the somatic H1 types, although these were not positively identified by mass spectrometry. f, listing of mass spectrometry-identified proteins from the indicated gel slice in d.

We also isolated histones from pronuclei assembled in interphase egg extract from sperm chromatin. We incubated demembranated sperm chromatin in low speed supernatant of Xenopus eggs until mid-S-phase (as determined by the 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole-stained appearance of the nuclei) and isolated the chromatin through a sucrose cushion. We then used conventional acid extraction to isolate those histones from the pelleted chromatin (Fig. 1D, lane 2). We have denoted these as “early embryo equivalent” histones, since that concentration of pronuclei is equivalent to the DNA/cytoplasm ratio at or before the midblastula transition. Fig. 1d (lane 1) shows the acid-extracted histones from sperm chromatin before incubation in egg extract. The remodeling of chromatin-bound proteins promoted by incubation of sperm chromatin and also of erythrocyte chromatin in egg extract was dramatic, as illustrated by the Coomassie-stained gel of the proteins acid-extracted from the chromatin (Fig. 1, d and e). Therefore, we identified a number of the proteins present on the remodeled chromatin by mass spectrometry, as tabulated in Fig. 1f. Remarkably, the more physiological embryonic pronuclei produced by incubation of sperm chromatin, and the exogenous addition of terminally differentiated erythrocyte nuclei resulted in an almost identical deposition of proteins (as apparent in the Coomassie-stained bands). This is consistent with the known ability of the Xenopus egg extract in reprogramming somatic nuclei. The identified proteins that are not present in the sperm sample alone but are observed upon remodeling of the sperm in egg extract include a variety of maternal (egg) factors that are necessary for a variety of cellular processes, including the embryonic histone H1 variant (B4), high mobility group proteins that are involved in remodeling chromatin, DNA replication factors (replication factor C and proliferating cell nuclear antigen), and the maternal histone chaperone nucleoplasmin (Fig. 1f).

In Fig. 1d, we also highlight the presence of a previously unidentified Xenopus sperm-specific linker histone H1-variant annotated as “H1fx” in the NCBI data base (GI # 83318207), with about 50% homology to mammalian H1x protein (supplemental Fig. S1). H1x is an H1-variant that appears to be present in chromatin inaccessible to micrococcal nuclease, although very little is known about it (35). We also identified the sperm-specific basic protein 4, as determined by mass spectrometry of the gel slices. Intriguingly, there is some evidence that sperm-specific basic proteins are related to the H1x family of proteins (36). These two proteins are rapidly lost from decondensing sperm pronuclei in egg extract.

We also isolated histones from two Xenopus cultured cell lines, one derived from a neurula explant (S3 cells) and one from adult kidney (A6), as well as from the nucleated erythrocytes of an adult frog. In total, these tissues (oocyte, egg, sperm, early embryo pronuclei, S3, A6, and erythrocyte) give a life span representation of cell types of the frog. The isolated histones were evenly loaded on gels and then Coomassie-stained (Fig. 2a).

FIGURE 2.

Isolation and relative enrichment of histone proteins and histone variants in embryonic and somatic cells. a, Coomassie-stained gel of histones isolated from the chaperone-complexed stored population in oocytes and eggs and the acid-extractable chromatin-associated sperm histones, early embryo equivalent (pronuclei) histones, S3 tissue culture histones, A6 tissue culture histones, and erythrocyte histones. The position of the core histones is noted as well as the putative location of the variety of histone H1 proteins in each cell type. b, Western blots of the histones isolated in 2a using antibodies against histone H3, H4, H2A, and H2A.Z.

We then immunoblotted these samples for the core histones H2A, H3, and H4 and for the H2A variant H2A.Z (Fig. 2b). Note that although H3 and H4 are evenly represented among the tissue types, H2B abundance is substantially decreased in the sperm, and a number of variants of H2A are apparent, including a doublet in the oocyte, egg, and early embryo samples. The slightly higher molecular weight H2A isoform is an embryo-specific H2A.X.4

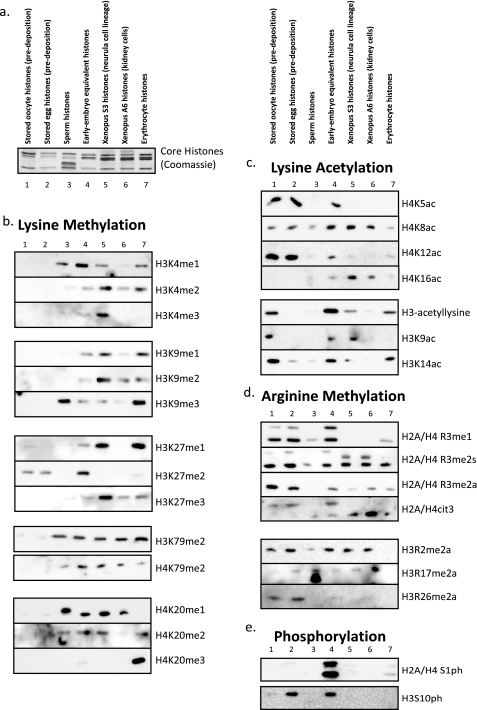

We then applied a large collection of post-translational modification-specific antibodies to this collection of histones (Coomassie stain of histones shown in Fig. 3a, cropped from Fig. 2a for clarity and reference). Fig. 3b shows the relative enrichment of lysine methylation states (mono-, di-, and trimethylation) on H3K4, H3K9, K3K27, H3K79, H4K79, and H4K20. Note that lysine methylation is underrepresented in the embryonic cell types (oocyte and egg in particular) and more abundant in somatic cell types. Fig. 3c shows the relative enrichment of lysine acetylation on H4K5, H4K8, H4K12, and H4K16 and on histone H3 and specifically on Lys9 and Lys14. Note that H4 lysine acetylation has a relatively high abundance in the stored oocyte and egg samples, consistent with the known predeposition role for the acetylation.

FIGURE 3.

Relative enrichment of histone post-translation modifications in embryonic and somatic cells. a, a cropped view of the Coomassie-stained gel from the isolated histones in a presented to show the core histones for reference and alignment with the blots in this figure. b, Western blots of the isolated histones with antibodies specific for a range of specific lysine methylation states, as indicated beside each blot. c, Western blots of the isolated histones with antibodies specific for a range of specific lysine acetylation states, as indicated beside each blot. d, Western blots of the isolated histones with antibodies specific for a range of specific arginine methylation states, as indicated beside each blot. e, Western blot of the isolated histones with an antibody against phosphorylated Ser1 of H2A and H4.

Fig. 3d shows the relative abundance of arginine methylation states on H2A and H4 R3 (mono-, symmetric di-, and asymmetric dimethylation), the H2A/H4 citrulline 3 deiminiation product, and on H3 Arg2, Arg17, and Arg26. In contrast to lysine methylation, arginine methylation is overrepresented in the embryonic tissue types relative to the somatic cell types. Note that we observed that Arg3 methylation was more abundant on H2A.X than on canonical H2A in the oocyte and egg, hence its slower migration (lanes 4 and 5) compared with the R3me-stained band in the somatic cells (lanes 5 and 6) (also data not shown).

We then probed these histones for phosphorylation on H2A/H4 Ser1, which is extremely abundant in the early embryo fraction, consistent with the rapid cell cycle status of that fraction and the known enrichment of S1ph during S and M phases. Finally, we probed the histones for phosphorylation on H3S10, known to be a potent marker of mitosis but also involved in transcriptional activation and meiotic maturation of oocytes (37). Note that H3S10ph was mainly enriched in nonmitotic fractions of histones.

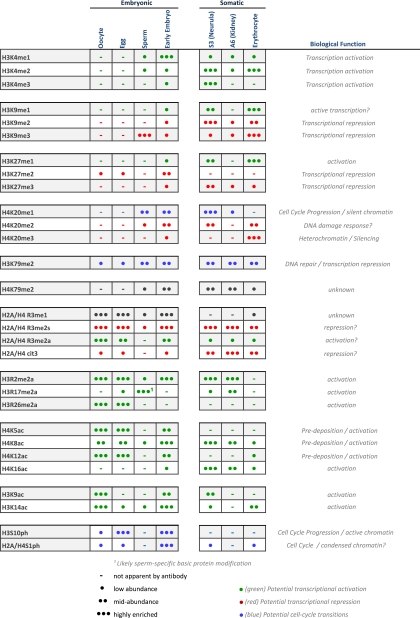

We were intrigued by the idea that the total global population of histone modifications may provide a simple “index” to categorize a particular cell type. Therefore, we tabulated the relative abundance of each histone modification as apparent in the Western blots in Fig. 3. We approximated relative quantitation comparing bands within each blot and not between discrete blots. The relative values ranged from no visible band to at or close to chemiluminescence saturation. We categorized them as follows: not apparent by antibody, low abundance, midabundance, and highly enriched, as illustrated in Table 1. We then tabulated these values for each modification and each cell type. We highlighted in red those modifications that have been correlated with transcriptional repression and silencing, those modifications that have been correlated with transcriptional activation in green, and those modifications correlated with cell cycle transitions in blue.

TABLE 1.

The pattern of histone post-translational modification enrichment indexes different cell types A qualitative relative abundance representation of the Western blots in Fig. 3 is show. (-), modifications not apparent by immunoblot; •, low relative (within the same blot) abundance; ••, mid relative abundance; •••, high relative abundance. The currently ascribed biological roles for each of the modifications are listed on the right. Those modifications correlated with transcriptional activation are colored green, whereas those modifications correlated with transcriptional repression and silencing are colored red.

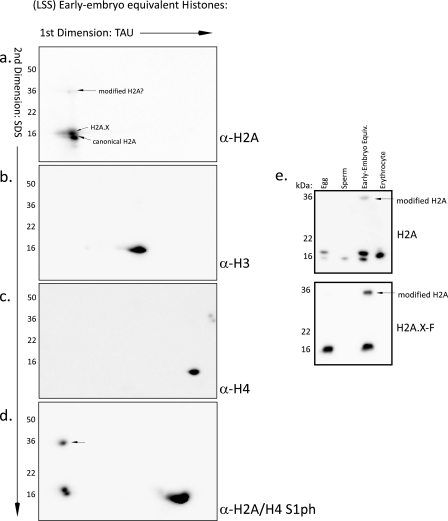

Since the relative abundance of histone modifications was so dramatically different between cell types, we also performed two-dimensional Triton-acid urea/SDS gel analysis of a number of the histone samples. This technique resolves all of the histone proteins (core histones, variants, and H1 isoforms) into discrete gel bands suitable for analysis by immunoblotting or mass spectrometry (31). Fig. 4a shows stored histones in the egg run on a two-dimensional TAU/SDS gel and Coomassie-stained. Fig. 4b shows acid extract sperm histones run on a two-dimensional TAU/SDS gel, whereas Fig. 4c shows the early embryo equivalent pronuclei acid-extracted histones run on a two-dimensional TAU/SDS gel. Finally, Fig. 4d shows somatic, terminally differentiated erythrocyte histones run on a two-dimensional TAU/SDS gel. The major stained bands were cut out and subjected to digestion and mass spectrometry for positive identification of the proteins in each location. The identified histone and chromatin proteins are indexed below each gel corresponding to the number gel band. The full results, listing nonchromatin proteins, number of identified peptides, and the corresponding GI numbers for those identified proteins in the two-dimensional gel are listed in tables in supplemental Fig. 3. Note that the mass spectrometry analysis of the sperm histones showed peptides from all four core histones appearing in a majority of those spots; we have eliminated listing of the overlap of core histones from Fig. 4.

FIGURE 4.

Two-dimensional TAU/SDS gel analysis demonstrating remodeling of histones during development. a, Coomassie-stained two-dimensional gel run with isolated Xenopus egg histones. The numbered stained gel bands were cut out and subject to mass spectrometry identification. The identified proteins are listed below the gel. b, Coomassie-stained two-dimensional gel run with isolated Xenopus sperm histones. c, Coomassie-stained two-dimensional gel run with isolated Xenopus pronuclei histones (early embryo equivalent histones). The numbered stained gel bands were cut out and subjected to mass spectrometry for identification. The identified proteins are listed below the gel. d, Coomassie-stained two-dimensional gel run with isolated Xenopus erythrocyte histones. The numbered stained gel bands were cut out and subjected to mass spectrometry for identification. The identified proteins are listed below the gel.

For further identification of the location of the histone proteins on the two-dimensional TAU/SDS gel, we immunoblotted the early embryo equivalent (extract pronuclei) histones run on the gel. We blotted with antibodies against core histone H2A (Fig. 5a), histone H3 (Fig. 5b), and histone H4 (Fig. 5c). We observed that three spots on the two-dimensional gel were recognized by the H2A antibody. Two of the spots are located at the known location of the canonical H2A and the embryo-specific enriched H2A.X (noted on gel; Fig. 5a). There was an additional higher molecular mass band detected (∼35 kDa). We confirmed that this isoform was indeed an H2A isoform by blotting with known H2A modification-specific antibodies (Fig. 5d). H2A and H2A.X are both phosphorylated on Ser1 as observed on the typical mass (∼15 kDa) bands as well as the higher molecular mass band. Macro-H2A may also be modified on those sites, although the amino acid sequence differs slightly; no macro-H2A modification on Ser1 or Arg3 has been reported, however. Therefore, we also ran a collection of histones on SDS-PAGE and blotted with the acidic patch H2A antibody and an antibody specific for the embryonic H2A.X4 (Fig. 5e). Note the appearance of the identical mass-shifted H2A modified isoform in the H2A.X-specific blot. These observations and the mass spectrometry analysis positively identify this high molecular weight band as an isoform of histone H2A and/or H2A.X.

FIGURE 5.

Immunoblots of two-dimensional TAU/SDS gels from early embryo equivalent (pronuclei) histones. a, two-dimensional gel run with isolated Xenopus pronuclei histones. The gel was immunoblotted with an antibody specific for histone H2A; this antibody will identify most H2A isoforms, since it recognizes the acidic patch in the histone fold region. b, two-dimensional gel run with isolated Xenopus pronuclei histones. The gel was immunoblotted with an antibody specific for histone H3. c, two-dimensional gel run with isolated Xenopus pronuclei histones. The gel was immunoblotted with an antibody specific for histone H4. d, two-dimensional gel run with isolated Xenopus pronuclei histones. The gel was immunoblotted with an antibody specific for phosphorylated Ser1 of histones H2A and H4. e, purified histones from egg, sperm, early embryo equivalent pronuclei, and erythrocytes were run on a 17% SDS-polyacrylamide gel and blotted for H2A and the embryonic H2A.X. The modified, mass-shifted, H2A isoform is indicated on the blot.

Since the mass spectrometry analysis of the gel slices in Fig. 4c showed that ubiquitin peptides were present at that location in addition to peptides from canonical H2A and H2A.X and macro-H2A, we attempted to probe these gels and one-dimensional SDS gels of the histones with a number of anti-ubiquitin and anti-SUMO antibodies. However, these blots did not produce any signal (data not shown). This may be due to a very low level of ubiquitylated histone; however, we suspect that the antibodies are not adequate for robust detection of this modification. Furthermore, the mass shift (from ∼15-kDa core histone to ∼35 kDa) may indicate a “diubiquitylation” rather than mono- or polyubiquitylation or may represent an unknown and completely different covalent modification. Antibodies directed against macro-H2A did not identify any proteins (data not shown), and only a single macro-H2A peptide was identified upon mass spectrometry, compared with multiple peptides found for canonical H2A and H2A.X. Overall, these data suggest a substantial mass shift modification of embryonic H2A.

DISCUSSION

We have presented here the isolation and analysis of histones, histone variants, and histone post-translational modifications from seven discrete cell types from the frog X. laevis. This is the first reported “life span” analysis of global histone modifications from embryonic cell types to adult, somatic cell types. Furthermore, we presented a novel and robust approach for isolating the stored histones, complexed to chaperones, in the oocytes and eggs of the frog. Finally, we demonstrated the remodeling of histone and acid-extractable proteins that occurs on chromatin upon fertilization and in the early embryo.

The histone code hypothesis posits that post-translational modifications of histones, alone or in combination, promote specific DNA transactions (transcriptional activation, repression, chromatin compaction, cell cycle transitions, etc.) and encode epigenetic information (1). Multivalency, or the combination of a number of binding effectors to increase the specificity of the code, specifically extends this hypothesis (4). This further suggests that combinations of modifications on the histones are important for encoding epigenetic information regulating the usage of the underlying DNA. Therefore, this analysis of a larger landscape of histone modifications and the index for each cell type is a crucial step toward deciphering the histone code.

Isolation of Stored Histones in the Egg—We first set out to analyze the histones in the Xenopus egg. However, we were unable to reliably isolate the stored histones by any of the approaches described in the literature, including the original alcohol precipitation, as described by Adamson and Woodland (20, 28). The original presentation of that purification has been accepted as proof of the abundance of histones stored in the egg. However, the paper only demonstrates the presence of a population of proteins that runs on an acid-urea gel parallel to labeled marker histones. Furthermore, in our hands, simple acidification of the egg extract did not enrich histone proteins; nor did immunoprecipitation with anti-nucleoplasmin (the histone chaperone) antibodies appreciably enrich histones, suggesting that the histone proteins are highly shielded when stored in the egg (33). Conventional chromatography has been utilized to purify histones out of Xenopus eggs (15), but this procedure resolved the histones into many subpopulations and therefore is not easily useful for further study. Therefore, we developed a novel approach for the isolation of histone proteins using heparin-Sepharose, a chromatography resin that effectively simulates DNA and thereby captures the histones. Using this simple chromatography approach, we were able to recover the vast majority of the histone proteins from egg extract in a single fraction and in a highly enriched form in solution.

Note that we were unable to isolate the actual maternal chromatin, rather than the stored, predeposition histones, for analysis due to the small size of the chromatin relative to the egg and the exceedingly large number of eggs we would need to acquire an appreciable quantity for study.

Identification of Histone Variants—We identified a novel H1 linker histone variant in Xenopus sperm called H1fx (alternatively called H1x) (36). The protein sequence is shown in alignment with human H1fx in supplemental Fig. 1. This protein appears to be quite abundant on the sperm chromatin but rapidly lost upon pronucleus formation. It probably serves to assist the protamines and sperm-specific basic proteins in the exceedingly tight condensation of sperm chromatin. We also identified an H1B variant in sperm chromatin that we called H1B.Sp; this sequence is shown in supplemental Fig. 2. The function and significance of these variants is presently unknown, although since they are only present in sperm, they are probably involved in the potent condensation of sperm chromatin.

We further show that histone H2A has a highly enriched population of H2A.X; this specific H2A.X isoform is to be described by us in a forthcoming paper.4 Finally, the H2A variant H2A.Z is at reduced levels in the egg, sperm, and early embryo, suggesting that its role in heterochromatin boundary formation (39) is not required until later in development. Since the egg is effectively a “reprogramming” machine, somatic molecular definitions of heterochromatin and euchromatin may not be fully delineated on embryonic chromatin, consistent with a reduced quantity of H2A.Z.

Identification of Histone Post-translational Modifications—Intriguingly, the Western blots with many histone post-translational modification antibodies show a distinct set of enriched modifications for each cell type. This strongly suggests that the accumulated and perhaps multivalent histone code of post-translational modifications is, at a minimum, a marker of a particular state of differentiation. It might also suggest that the index of post-translation modifications could be predictive for a cellular state of differentiation, although we do caution that these results do not imply causality between a particular modification and cellular phenotype.

A number of obvious patterns emerged from this analysis of histone PTMs. First of all, preexisting lysine methylation was very low in the embryonic samples, in particular the oocyte, egg, and sperm. Aside from the abundant H3K9me3 in sperm, consistent with sperm as a transcriptionally silenced template, no other embryonic lysine modification was enriched to a level approaching any of the somatic cells. Reciprocally, arginine methylation was robust in the egg and oocyte while mostly nonexistent in the sperm (except perhaps for the sperm-specific basic protein 4). Arginine methylation has been correlated with pluripotency in early development and development of primordial germ cells (40, 41), suggesting an important role for this modification subtype in specifying developmental roles. We also saw distinctly different patterns for mono, disymmetric, and diasymmetric arginine methylation on histones H2A and H4, suggesting distinct roles for each of these modifications. Each of these subsets of arginine methylation may be catalyzed distributively by one or more enzymes (41). Finally, citrullination of the arginine or methylarginine may antagonize the methylarginine state (42). Methylarginine also appears to be less enriched in somatic and dividing cells (S3 and A6) and almost completely eliminated in terminally differentiated somatic cells (erythrocytes).

Remarkably consistent with the known examples of the histone code, the terminally differentiated erythrocytes, which are completely silenced and undergo little if any transcription (43), show the highest relative levels of silencing marks and low relative levels of activation marks. In particular, erythrocytes exhibit abundant H4K20me3, the prototypical heterochromatin modification, as well as high levels of H3K9me3. It will be quite intriguing for future analysis to probe the change in these modifications, especially at important embryonic loci, upon reprogramming in egg extract. Since reprogramming of somatic nuclei requires progression through mitosis first (44), terminally differentiated cells may need to switch from high H4K20me3 levels to H4K20me1, or other cell cycle-associated PTMs. Active histone demethylases are likely to be important for this process, since dilution via new histone deposition is unlikely to account for these putative changes.

We did not observe any clear correlation between lysine acetylation and state of development. This is not surprising, since acetylation is considered among the most transient histone modifications and may perform more of its function by cis-chromatin electrostatic repulsion rather than by recruiting trans-acting proteins. Sperm histones had no appreciable acetylation, whereas oocyte and egg histones had abundant H4K5, H4K8, and H4K12 acetylation. H4K5 and H4K12 are known “predeposition” marks, associated with DNA replication and chromatin assembly (16). Since the histones stored in the egg are prepared for rapid chromatin assembly during early development, this observation is expected and consistent with previous observations. The existence of predeposition K8ac was previously unknown. Intriguingly, H3 was acetylated on Lys9 and Lys14 in the oocyte but lost in the egg and regained in the early embryo, suggesting that H3 acetylation is dynamic in the early embryo. Our observations are reminiscent of the recent demonstration of the proposed “potentiating” role for H3K9me and H3K14ac predeposition modifications in cultured mammalian cells (25).

Finally, H3S10 and H2A/H4S1 phosphorylation were most abundant in the early embryo equivalent fraction of histones, consistent with the rapid chromatin transitions that occur in this sample and the known roles of these modifications in cell cycle transitions and meiotic maturation (37).

Early Embryo Histone Dynamics—The change in histone abundance and histone PTMs from the oocyte to egg to sperm to early embryo were dramatic. This is not surprising, considering the major biological rearrangements (changes in DNA/protein ratio, chromatin condensation, heterochromatin/euchromatin status, DNA replication, and transcription status) and changes in programming that occur during these transitions. Note the shift to linker histone B4, the embryonic linker histone, from the H1fx (similar to H5) in the sperm. There is also a pronounced accumulation of two distinct H2A isoforms that react with the acidic patch H2A antibody in the oocyte and the egg, not present in the sperm. Most significantly, there are distinct changes in histone PTMs that are likely to be significant in the biology of reprogramming and embryonic pluripotency, highlighted in Table 1. In particular, we point out the accumulation of H3K4 methylation, suggesting an acquired competence for transcription; the establishment of H3K27 methylation in the pronucleus, which along with K4me may form bivalent domains that set up later developmental transitions (38); the loss of H3K9me3 from the sperm upon incubation in the egg extract and pronucleus formation, implying a loss of transcriptional repression; the shift in H4 acetylation from a very high level of “predeposition” marks when stored in the egg to a lower level when deposited in the pronuclear chromatin; and finally the exceedingly enriched H2A/H4S1ph in the early embryo, perhaps a mark of very actively turned over histones within chromatin.

In summary, our data suggest that the state of relative enrichment of histone post-translational modifications does vary dramatically from cell type to cell type and from embryonic to somatic cells. These observations are consistent with an indexing function for these modifications and relative abundances of histone variants to distinguish the molecular epigenetic signature for each cell type. Furthermore, by indexing cell types, these PTMs probably serve, in a localized fashion on discrete populations of nucleosomes within the cell, as a multivalent handle for effectors (“readers” and their associated remodelers and transcription machinery) to serve their function. We do note, however, that our observations do not support, nor do they refute, a “predictive” histone code, in which the recorded life span modification transitions have a casual effect on cellular outcome.

Further work is necessary to distinguish between the global relative abundance of these PTMs and their localized role in parallel sets of cell types. Newly developed techniques, in particular chromatin immunoprecipitation-sequencing technologies, will be invaluable to deciphering the details of the molecular functioning of the histone code. Our continued use of the Xenopus model system will be especially fruitful, since it is uniquely situated for biochemical analysis of pre- and post-deposition histones, cell-free reconstitution of mechanisms, and probing the developmental significance of the histone code.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Hiro Funabiki and members of the Funabiki laboratory for generously sharing the frog colony, Jim Maller for Xenopus A6 and S3 cell lines, and Aude Dupre and Jean Gautier for instruction on oocyte extraction. We are especially thankful to Sandra Hake and Laura Banaszynski for constructive comments on the manuscript.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health National Research Service Award/Kirschstein Fellowship GM075486 (to D. S.), Grant GM37537 (to D. F. H.), and Grant GM53512 (to C. D. A.). This work was also supported by Rockefeller University. The costs of publication of this article were defrayed in part by the payment of page charges. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. Section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental Figs. 1–3.

Footnotes

The abbreviations used are: DTT, dithiothreitol; HPLC, high pressure liquid chromatograph; PTM, post-translational modification.

D. Shechter, unpublished observation.

D. Shechter, R. K. Chitta, J. Shabanowitz, D. F. Hunt, and C. D. Allis, submitted for publication.

References

- 1.Strahl, B. D., and Allis, C. D. (2000) Nature 403 41-45 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Malik, H. S., and Henikoff, S. (2003) Nat. Struct. Biol. 10 882-891 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bernstein, E., and Hake, S. B. (2006) Biochem. Cell Biol. 84 505-517 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ruthenburg, A., Li, H., Patel, D., and Allis, C. (2007) Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 8 983-994 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Taverna, S., Li, H., Ruthenburg, A., Allis, C., and Patel, D. (2007) Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 14 1025-1040 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Garcia, B., Shabanowitz, J., and Hunt, D. (2007) Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 11 66-73 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lin, R., Leone, J. W., Cook, R. G., and Allis, C. D. (1989) J. Cell Biol. 108 1577-1588 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Turner, B., and Fellows, G. (1989) Eur. J. Biochem. 179 131-139 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Berger, S. L. (2007) Nature 447 407-412 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Czermin, B., and Imhof, A. (2003) Genetica 117 159-164 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Huen, M., Sy, S., van Deursen, J., and Chen, J. (2008) J. Biol. Chem. 283 11073-11077 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Barber, C. M., Turner, F. B., Wang, Y., Hagstrom, K., Taverna, S. D., Mollah, S., Ueberheide, B., Meyer, B. J., Hunt, D. F., Cheung, P., and Allis, C. D. (2004) Chromosoma 112 360-371 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Barski, A., Cuddapah, S., Cui, K., Roh, T. Y., Schones, D. E., Wang, Z., Wei, G., Chepelev, I., and Zhao, K. (2007) Cell 129 823-837 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kleinschmidt, J. A., Seiter, A., and Zentgraf, H. (1990) EMBO J. 9 1309-1318 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zucker, K., and Worcel, A. (1990) J. Biol. Chem. 265 14487-14496 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Allis, C. D., Chicoine, L. G., Richman, R., and Schulman, I. G. (1985) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 82 8048-8052 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Almouzni, G., Méchali, M., and Wolffe, A. (1990) EMBO J. 9 573-582 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Maller, J., Gross, S., Schwab, M., Finkielstein, C., Taieb, F., and Qian, Y. (2001) Novartis Found Symp. 237 58-73 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Woodland, H. (1980) FEBS Lett. 121 1-10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Adamson, E., and Woodland, H. (1974) J. Mol. Biol. 88 263-285 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Laskey, R., Mills, A., and Morris, N. (1977) Cell 10 237-243 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ruderman, J., Woodland, H., and Sturgess, E. (1979) Dev. Biol. 71 71-82 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Funabiki, H., and Murray, A. (2000) Cell 102 411-424 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Woodland, H. (1979) Dev. Biol. 68 360-370 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Loyola, A., Bonaldi, T., Roche, D., Imhof, A., and Almouzni, G. (2006) Mol. Cell 24 309-316 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gilbert, N., Boyle, S., Sutherland, H., de Las Heras, J., Allan, J., Jenuwein, T., and Bickmore, W. A. (2003) EMBO J. 22 5540-5550 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Adamson, E., and Woodland, H. (1977) Dev. Biol. 57 136-149 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Woodland, H. R., and Adamson, E. D. (1977) Dev. Biol. 57 118-135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shechter, D., Costanzo, V., and Gautier, J. (2004) Nat. Cell Biol. 6 648-655 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Humphries, S., Young, D., and Carroll, D. (1979) Biochemistry 18 3223-3231 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shechter, D., Dormann, H., Allis, C., and Hake, S. (2007) Nat. Protoc. 2 1445-1457 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shevchenko, A., Wilm, M., Vorm, O., and Mann, M. (1996) Anal. Chem. 68 850-858 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dilworth, S., Black, S., and Laskey, R. (1987) Cell 51 1009-1018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schmiedeke, T. M., Stockl, F. W., Weber, R., Sugisaki, Y., Batsford, S. R., and Vogt, A. (1989) J. Exp. Med. 169 1879-1894 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Happel, N., Schulze, E., and Doenecke, D. (2005) Biol. Chem. 386 541-551 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Frehlick, L., Prado, A., Calestagne-Morelli, A., and Ausió, J. (2007) Biochemistry 46 12700-12708 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schmitt, A., Gutierrez, G. J., Lenart, P., Ellenberg, J., and Nebreda, A. R. (2002) FEBS Lett. 518 23-28 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bernstein, B. E., Mikkelsen, T. S., Xie, X., Kamal, M., Huebert, D. J., Cuff, J., Fry, B., Meissner, A., Wernig, M., Plath, K., Jaenisch, R., Wagschal, A., Feil, R., Schreiber, S. L., and Lander, E. S. (2006) Cell 125 315-326 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Meneghini, M. D., Wu, M., and Madhani, H. D. (2003) Cell 112 725-736 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wysocka, J., Allis, C. D., and Coonrod, S. (2006) Front. Biosci. 11 344-355 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bedford, M. T., and Richard, S. (2005) Mol. Cell 18 263-272 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wang, Y., Wysocka, J., Sayegh, J., Lee, Y. H., Perlin, J. R., Leonelli, L., Sonbuchner, L. S., McDonald, C. H., Cook, R. G., Dou, Y., Roeder, R. G., Clarke, S., Stallcup, M. R., Allis, C. D., and Coonrod, S. A. (2004) Science 306 279-283 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dimitrov, S., and Wolffe, A. (1996) EMBO J. 15 5897-5906 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lemaitre, J., Danis, E., Pasero, P., Vassetzky, Y., and Méchali, M. (2005) Cell 123 787-801 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Nicklay, J. J., Shechter, D., Chitta, R. K., Garcia, B. A., Shabanowitz, J., Allis, C. D., and Hunt, D. F. (2009) J. Biol. Chem. 284 1075-1085 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.