Shaping the Research That Informs Inclusive Policy

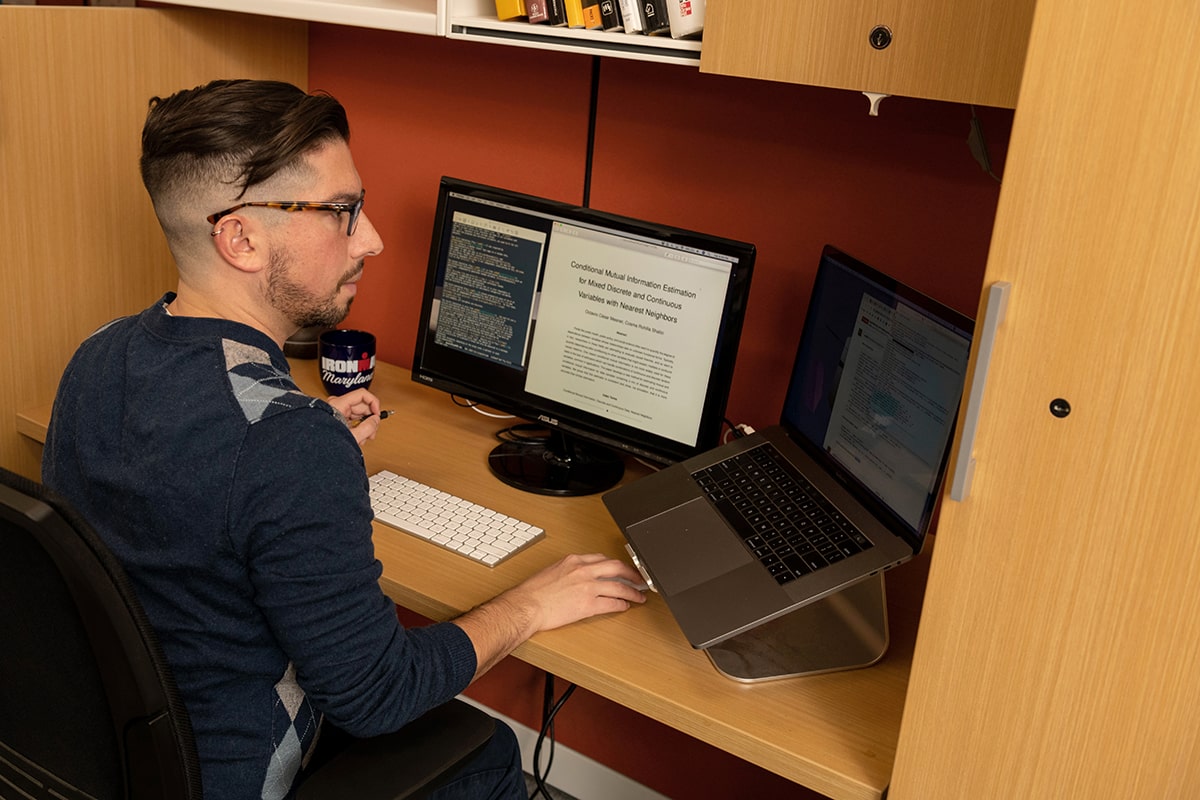

Ironman grad student combines machine learning, statistics and engineering to increase representation for underserved populations

By Katy Rank Lev

Media Inquiries- Media Relations

- 412-268-2902

- College of Engineering

- 412-268-6151

Octavio Mesner is fascinated by ripple effects — or, as epidemiologists call them, causal pathways.

For instance, he never imagined being diagnosed with a language processing disorder as a child would lead to his focus on math, which led him to a master's degree in biostatistics, which ultimately led him to pursue a combined Ph.D. at Carnegie Mellon University in engineering and public policy and in statistics and data science.

But he now sees the ways in which his early emphasis on STEM contributed to his methodical research habits. He knows that the increased effort he had to put toward learning to read helped him build the resilience necessary to embark upon graduate statistics classes without having studied this subject before.

"It's amazing to me how you can use data and statistics to inform policy," he said. "I want to see, quantitatively, what outcomes we can expect with each policy alternative."

Policy is not Mesner's first vocation. Initially, he wanted to join the priesthood. Such a journey seemed at odds with his identity as a gay Latino, but Mesner said, "I wanted my life's work to contribute to social good." At the time, the Capuchin Franciscan Seminary seemed like the road to societal influence.

Mesner was a bit of an outlier among the friars. In a space where most students focused on philosophy, Mesner majored in math. Amid a religious community that limited the relationships available to him as a gay man, Mesner said he broadened his intellectual habits and redefined his spiritual beliefs. "I just learned a ton there," he said. "The experience got me asking questions about myself, about church teachings, and opened my mind in a huge way."

Following a break from Catholicism, Mesner felt a bit unmoored. Still aiming to devote his work to the greater good, he decided to pursue a master's degree in biostatistics and, in his spare time, decided to train for triathlons. Joining the DC Triathlon Club in Washington, D.C., introduced him both to intentional, dedicated training methods and a group of multi-faceted athletes who relentlessly pursued improvement.

"They were amazing people to be around," said Mesner, who is modest about his own achievements — he completed his third Ironman competition during his Ph.D. coursework. These grueling races include a multi-mile swim, a bike race of over 100 miles, and end with a full marathon.

Training for such an event involves as much mental clarity as it does physical endurance. Lucky for Mesner, his time in seminary taught him meditation and stillness — habits that contributed to his ability to log dozens of miles each week on top of graduate studies.

Once he completed his master's, Mesner was recruited by his department chair to work for a collaborative nonprofit funded by both the Department of Defense and the National Institutes of Health. The infectious disease clinical research program taught Mesner how poignantly numbers could tell a story.

"In one study, we examined military personnel living with HIV who were subsequently infected with syphilis," Mesner explained. The medical community was unsure how to treat an immunocompromised person with antibiotics for a syphilis infection — what dosage was appropriate? Which specific type of antibiotic would be most impactful? "From the thousands of cases of syphilis in the US Military HIV Natural History Study, we saw no statistical significance in using a greater dosage of penicillin to treat a patient for syphilis who was also living with HIV," Mesner said.

He clarified that Centers for Disease Control guidelines already indicated this treatment protocol, but there were differing opinions among the medical community on this guideline. In fact, some doctors wrote a response questioning our findings. "Fortunately, we were very meticulous," Mesner said. "Biostatistical models help doctors make sense of large datasets. I think that's how science should always be done. I'm a firm believer in not bringing in your opinion about causal mechanisms to data analysis."

Studying military personnel affected by sexually transmitted disease was a paradigm-shifting opportunity for Mesner. Because the United States Military has universal healthcare for its service members, researchers like Mesner have an unparalleled data set available to them. "I don't know if I will ever have another data set that rich," Mesner explained.

As he pursues a dual Ph.D. at Carnegie Mellon, Octavio Mesner has dedicated his academic career to tackling challenges of profound societal consequence. He has been authored or co-authored at least six publications in prestigious global periodicals. Most recently, Mesner won a Ford Foundation Fellowship — a distinguished social justice award from the National Academy of Sciences that aims to increase faculty diversity in higher education.

He did, however, notice a significant lack of risk behavior information prior to the repeal of the Clinton Administration's "don't ask, don't tell" policy. The majority of the data in his syphilis study was collected prior to 2010 when the United States Armed Forces finally began to allow service members to disclose their sexual orientation and behaviors openly.

"Before that point, we couldn't ask patients about sexual risk behaviors. Doctors could report patients and they risked losing their livelihood. In addition to relegating an entire group of people, this policy hurt the science. It was impossible for us to fully understand how risk behaviors were empirically connected with health outcomes," Mesner said. Nearly a decade later, the data is still skewed. "HIV infection data is male-heavy, and it's still taboo to talk about."

He began to look at the types of data that were missing — statistically and epidemiologically, it matters if a gay male is the insertive or receptive partner, and this information is not often recorded. "We don't have an N to compare anything to when we study this population. These are downstream policy effects I wish people would think about," Mesner said.

Gradually, he became aware that he could be a person influencing policy. "I really, really care about using data to support policy decision-making," he said. He discovered the field of engineering and public policy and was taken aback that his reach school, CMU, offered him a spot and encouraged him to tack on an emphasis in statistics to boot.

"That was one of the happiest moments of my life other than when my partner proposed," Mesner said.

And then he looked at the reality of the work load involved in double majoring for a Ph.D. program.

He fell into the "imposter syndrome" many CMU students experience when they first arrive at a campus burgeoning with such innovative ideas. "When I came here, I saw that everyone here is brilliant," he said. "I started to worry about why I was accepted."

Despite his concerns about his qualifications, Mesner delved into unfamiliar fields of study. He took electives in machine learning and economics and struggled, but now finds the course materials to be directly applicable to his dissertation research.

"I started to think, this is like training for an Ironman," he said. "If I was regimented, I could do it."

Mesner decided to work toward downstream positive effects for CMU. With the same deliberate planning he gave to his athletic training, Mesner began to explore intersectional connection opportunities for LGBTQ+ people of color.

"CMQ+ asked me to be treasurer, which I thought was the worst job," he said in reference to a campus organization supporting graduate students in the LGBTQ+ community. "But I also feel like if nobody does this work, these organizations can't exist." Mesner was soon also invited to join the President's Task Force on Campus Climate, where he engaged with people who shared his concerns.

For example, Mesner noticed University Health Services was not offering a specific type of test for sexually transmitted infections (STI). Mesner met with Noah Riley from Health Promotion to see what could be done.

"Octavio wanted to understand more about why UHS was not offering the testing, and to begin a conversation about opportunities CMU had to increase access to this type of care," said Riley. The testing in question requires the care of a specialist, but through the conversation Riley formed a collaborative relationship with Mesner. As Riley got to know Mesner, he observed that Mesner "always makes sure students standing at intersecting identities are represented and heard.”

Riley's office typically hosts pop-up events around STI awareness and testing to capture students who wouldn't normally seek this type of treatment. "Before I met Octavio, we never really had a lot of partnership or collaboration for those events," said Riley. "Octavio initiated all of that."

Mesner's relationship with the staff at UHS helped him think about university policy as a microcosm of the government policy he hopes to help shape. He said, "At CMU, in order to be a student, you have to have health insurance. This means everyone is less likely to get sick because everyone has access to medical care. It protects the entire community."

His research aims to link numerous, seemingly unrelated variables, to hopefully protect communities, similar to the way his beloved Ironman competitions unite seemingly unrelated athletic endeavors.

"I'm trying to develop a non-parametric exploratory data analysis method where epidemiologists (or other researchers) can enter a data set and get back a diagram estimating what variables are causing what." Mesner is developing the theory and writing the code in hopes of applying the method to a survey of 10,000 gay men on sexual risk behaviors and outcomes. He said, "I think this will be particularly interesting because in 2012, the FDA approved a drug that can significantly reduce the risk of HIV acquisition. The question now is, how does this affect sexual risk behavior like condom use? Might we see a higher frequency of other infections? Hopefully my work will help epidemiologists see how risk factors are related."

Citing a current example, Mesner explained that data from China showed that the novel coronavirus had a more dramatic effect on men compared to women. "There are so many questions swirling around. Is this because men are more likely to smoke and this is a respiratory infection? Are there differences in the immune systems of the sick patients? Having a more robust data analysis tool will give us places to look."

The combination of statistics and data science with engineering and public policy at CMU has given Mesner the additional tools he needs to help provide structure to complex datasets with this hope of informing further research and policy. He graduates in July, when he will move on to a post-doctoral fellowship in statistics at the University of Michigan.

"I want to contribute to policy that supports all the diverse groups throughout this country," he said. "It makes me feel so good to be part of science that supports people."

Mesner first attempted a triathlon in 2011 and found he loved the combination of events more than he enjoyed them individually. Pictured here, in the bike portion of the 2017 Maryland Ironman, he raced 112 miles in 5:31:55.