Conservation: Title II

Provides assistance to agricultural producers and landowners to adopt conservation activities on agricultural and forest lands to protect and improve water quality and quantity, soil health, wildlife habitat, and air quality.

Highlights

- Increases mandatory funding for conservation programs by a total of roughly 2 percent during 2019-2023.

- Continues working land program funding, as a share of total conservation funding, at the same level as under the Agricultural Act of 2014 (2014 Farm Act).

- Increases Conservation Reserve Program (CRP) acreage cap from 24 million acres to 27 million acres by 2023.

- Increases funding for the Environmental Quality Incentives Program (EQIP), the Agricultural Conservation Easement Program (ACEP), and direct funding for the Regional Conservation Partnership Program (RCPP).

- Continues the Conservation Stewardship Program (CSP), but at a reduced funding level, and replaces an acreage cap with a funding cap.

New Programs and Provisions

Conservation Reserve Program (CRP)—Continues funding for payments to producers who maintain cropland, marginal pasture, or grassland in grass or tree cover for 10-15 years. The overall acreage cap is gradually increased from 24 million acres to 27 million acres in FY2023. Within the overall cap for FY2023, goals are established of 8.6 million acres for continuous signup and 2 million acres for grasslands. Land that was in CRP under a 15-year contract that expired in 2017 or 2018 is eligible for enrollment. A general signup is required each year. After each general signup, a ranking of grassland contract offers for enrollment is also required (grassland contract offers are accepted continuously).

The 2018 Act requires, to the maximum extent practicable, that 60 percent of acres available for CRP enrollment each year be allocated across States based on historical State enrollment rates. At least 40 percent of continuous enrollment is to be in water quality practices under the Clean Lakes, Estuaries, and Rivers (CLEAR) initiative to the maximum extent practicable. Expiring CRP contracts enrolled under CLEAR or other related water quality practices may also be enrolled in contracts of up to 30 years under a new CLEAR 30 Pilot Program. The Conservation Reserve Enhancement Program (CREP), which has been implemented administratively by USDA, is required by statute under the 2018 Act, which also includes a definition of eligible partner to include both state and nongovernmental partners.

The 2018 Act also sets upper limits on the county average soil rental rates used to set field-specific maximum annual payment rates and sets even tighter restrictions on maximum payment rates for re-enrollments. Incentive payments for continuous signup contracts continue; a payment of 32.5 percent of the first annual payment is required. $12 million is provided for a forest management incentive. Opportunities for routine harvesting, grazing, and other commercial activities on CRP land are expanded (with a reduction in annual payment).

The Soil Health and Income Protection Pilot Program (SHIPP) provides payments for farmers who establish grass cover on less productive cropland for a period of 3-5 years. The CRP Farmable Wetlands Program (FWP) is extended through 2023. The Transition Incentives Program (TIP), which supports the transition of land under expiring CRP contracts from contract holders to beginning or socially disadvantaged farmers, is continued with $50 million in funding. Under the 2018 Act, land can be transitioned from any contract holder (not just retired or retiring farmers).

Conservation Stewardship Program (CSP)—Continues financial assistance to producers who meet stewardship requirements on agricultural and forest lands. Under the 2014 Farm Act, CSP could enroll as many as 10 million new acres each year, at an average cost of $18 per acre. The 2018 Farm Act replaces the acreage cap with a funding cap and provides mandatory funding of $700 million for FY2019, $725 million for FY2020, $750 million for FY2021, $800 million for FY2022, and $1 billion for FY2023. CSP funding was $1.32 billion in FY2018 (estimated) and, had the 2014 Act provision been extended, was projected to be roughly $1.75 billion per year, on average, for FY2019-FY2023 according to the Congressional Budget Office (CBO). CSP contracts will no longer be eligible for a one-time automatic renewal. Producers seeking contract renewals will be required to compete with others seeking new or renewed contracts. Cover crop payments are increased, and supplemental payments are authorized for advanced grazing management, as are payments for the development of comprehensive conservation plans. A new Grassland Conservation Initiative is established within the CSP to assist producers in protecting grasslands for grazing and wildlife.

Environmental Quality Incentives Program (EQIP)—Continues financial assistance to producers to install and maintain conservation practices on eligible agricultural and forest land. The 2018 Act mandates funding of $1.75 billion in FY2019, $1.75 billion in FY2020, $1.8 billion in FY2021, $1.85 billion in FY2022, and $2.025 billion in FY2023. EQIP funding was $1.76 billion in FY2018 (estimated) and, had the 2014 Act provision been extended, was projected to be roughly $1.75 billion per year for FY2019-FY2023, according to the CBO. The share of funding set-aside for livestock-related practices is reduced from 60 percent to 50 percent while the set-aside for wildlife habitat practices is increased from 5 percent to 10 percent.

The new legislation also: (1) provides for higher incentive payment rates (up to 90 percent of costs) for highly beneficial practices; (2) establishes Conservation Incentive Contracts that provide both annual and cost-sharing payment for 5-10 years to encourage adoption of practices with broad resource benefits (e.g., cover crops, transition to resource conserving crop rotations); (3) allows irrigation districts, irrigation association drainage districts, and acequias (a political subdivision of a State organized to manage irrigation ditches; acequias cannot impose taxes or levies) to participate in EQIP for water conservation or irrigation efficiency practices; and (4) requires $25 million in Conservation Innovation Grant funding to be used for onfarm trials, including a soil health demonstration trial.

Agricultural Conservation Easement Program (ACEP)—Continues funding for long-term easements for the restoration and protection of onfarm wetlands and the protection of eligible agricultural land from conversion to nonagricultural uses. Program funding declined during FY2014-FY2018, averaging $405 million per fiscal year but declining to $250 million by FY2018. Program funding is $450 million per year for FY2019-FY2023. A series of amendments broadens program eligibility, improves enforcement, and provides additional flexibility in managing easements.

Regional Conservation Partnership Program (RCPP)—Provides assistance to partners to solve problems on a regional or watershed scale. The 2018 Farm Act increases mandatory direct funding to $300 million per year for FY2019-FY2023 but eliminates the requirement that 7 percent of funds from “covered programs” be transferred to and allocated through RCPP. RCPP direct funding was $100 million per year under the 2014 Farm Act. Under the new act, RCPP will function as a standalone program, rather than through covered programs. Covered programs, which now include the Conservation Reserve Program and Watershed Protection and Flood Prevention Act, will serve largely as a guide to the activities that can be funded through RCPP partnerships. The 2018 Act also requires the Secretary of Agriculture to provide guidance on quantifying natural resource outcomes for projects and allocates 50 percent of funding for State and multistate projects and 50 percent for projects centered on critical conservation areas.

Other Conservation Programs

- Mandatory funding is provided for the Small Watershed Rehabilitation Program ($50 million per year, indefinitely), Voluntary Public Access and Habitat Incentive Program ($50 million annually for FY2019-FY2023, including $3 million reserved to encourage public access to lands under Wetland Reserve Easements); and Grassroots Source Water Protection Program ($5 million available until expended).

- The Feral Swine Eradication and Control Pilot Program requires USDA to study the extent of damage from feral swine, develop eradication and control measures, and provide cost-sharing to farmers in pilot areas. Mandatory funding of $75 million is provided for FY2019-FY2023.

- Provisions to protect drinking water require USDA to use at least 10 percent of funding for conservation programs (except the Conservation Reserve Program) to encourage practices related to water quality and quantity that protect source waters for drinking.

Economic Implications

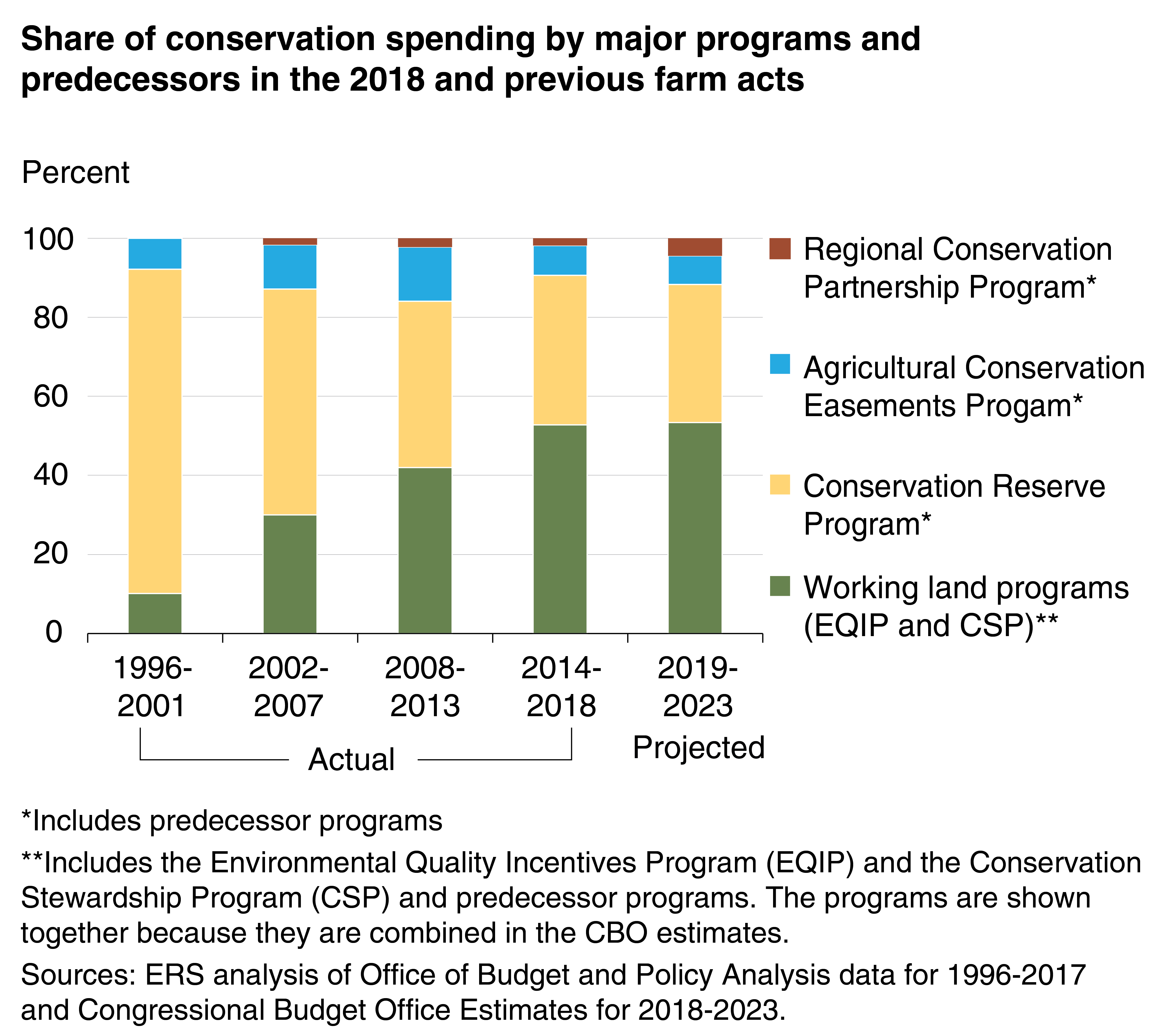

For FY2019-FY2023, the CBO projects mandatory spending on farm bill conservation programs that is slightly higher than projected baseline spending (spending under an extension of 2014 Farm Act programs, without modification, through 2023). For the five largest conservation programs (and predecessors), inflation-adjusted spending increased under both the 2002 and 2008 Farm Acts (2002-2013, see chart), but was lower under the 2014 Farm Act (2014-2018). CBO projections suggest that the 2018 Act could provide slightly higher funding, on average, than under the 2014 Act. Although program funding is mandatory (does not require appropriation), spending in future years is subject to congressional review and, under past farm acts, has sometimes been reduced from specified levels.

While overall conservation funding is roughly equal to baseline levels for FY2019-FY2023, the 2018 Act shifts funding among programs. The acreage enrollment cap in the Conservation Stewardship Program (CSP) is replaced with a funding cap that implies lower spending in the future. Contracts signed under the acreage-limited CSP will continue; contracts that expire before December 31, 2019 can be renewed. Going forward, the 2018 Act sets spending limits of $700 million for FY2019, increasing to $1 billion by FY2023. CSP funding was $1.32 billion in FY2018 (estimated) and was projected to be roughly $1.75 billion per year, on average, for FY2019-FY2023 according to the CBO. Over the next several years, as spending for existing CSP contracts ramps down and spending on new contracts ramps up, CSP spending will eventually reach an overall lower level of spending commensurate with new limits.

In contrast, EQIP funding is increased from $1.75 billion in FY2019 to $2.025 billion in FY2023, compared to an average baseline of $1.75 billion over FY2019-FY2023. Funding is also increased for the Agricultural Conservation Easements Program (from $250 million to $450 million annually) and the Regional Conservation Partnership Program ($100 million to $300 million annually). Conservation Reserve Program funding is projected to decline (a total of -$189 million) over FY2019-FY2023.

Changes in major conservation program funding under the 2018 Act will effectively halt the shift toward increasing the share of conservation funding for working land programs that began with the 2002 Act and continued under the 2008 and 2014 Acts. While funding has shifted toward working land programs in every farm bill since 2002, the size of the shift has declined in each subsequent farm act. Under the 2014 Act, working land program funding accounted for a majority (53 percent) of major conservation program funding for the first time. Under the 2018 Act, spending for working land programs will again account for about 53 percent of the five largest programs. (Working land programs are defined here to include EQIP and CSP. Other programs can also support working lands. ACEP can help preserve working agricultural land that would otherwise be developed. Some CRP continuous signup practices (e.g., filter strips) may also complement crop production. RCPP can fund a wide range of practices.)

While the overall acreage cap for the Conservation Reserve Program is increased from 24 million to 27 million acres under the 2018 Act, other changes could limit the size of annual rental payments and may reduce enrollment incentives. Annual rental rates could be affected by two provisions. The first affects the determination of county average soil rental rates (SRRs). County-average SRRs, which were equal to the county-average rental rate for non-irrigated cropland under previous farm acts, would be set 15 percent below county-average rates for general signup and 10 percent below county-average rental rates for continuous signup. Because county-average SRRs underlie CRP limits on annual rental payments, these provisions could result in rental payments as much as 15 percent lower for general signup and 10 percent lower for continuous signup. Actual limits established for CRP implementation can also include adjustments to the county-average SRR, including adjustments (up or down) for field-specific soil quality. The second new CRP provision applies only to land that has already been in CRP. For these lands, an overall countywide ceiling on annual rental rates would also apply. Annual rental rates could not exceed 85 percent of the county average rental rate (not the county-average SRR) for general signup and 90 percent for continuous signup.

The actual effect of these new limitations on CRP enrollment incentives is difficult to predict. Many CRP general signup participants offered to take less than the maximum annual rental payment to increase the likelihood of acceptance for their contract offer. Producer offers may also include annual rental payment bids that are higher than the minimum they would be willing to accept for enrolling land in CRP. For continuous signup, CRP incentive payments (that are in addition to basic annual rental and cost-share payments) are still authorized and could help maintain higher incentives for land entering through continuous signup. Under the 2018 Act, continuous signup contracts would include an incentive payment equal to 32.5 percent of the first annual rental payment. Other incentives could also apply. Finally, there is also a large pool of CRP-eligible land that has not yet been enrolled in the program, although attracting broader application may be difficult if annual rental payments are, in fact, lower under the 2018 Act.