Change Your Image

chaos-rampant

Thessaloniki, Greece.

PM me at bodhidharma.said@null.net

Reviews

Ash vs Evil Dead (2015)

Expansive and joyous

I had no idea this was out or I'd have come to it long ago. I've been a bit out of the loop for some time and it didn't register at all. But watching it over the span of a few days, it's a roaring success for the Raimis and I would probably count it in shortlist of my favorite horror films of the last decade.

There is gruesome splatter and goofy laughs as before; everything in tone and world is as you'd expect from Evil Dead. Once more Ash struts into a stage that swirls and comes alive around him. Once more the point is that everything is conjured up from thin air purely for the joy of making things up. Deadites leap out of nowhere to be chainsawed every minute, as well as other gnarly things. Characters become possessed or encounter their doubles, portals open to other dimensions, and all sorts of other shifts to and from illusory context. We even revisit that first cabin on the eve of the original film.

And the TV format allows this time ample space for us to explore. There are so many memorable places here and we're send in a freewheeling ride through them. And Bruce is ever so watchable, shifting between cocky hero and oafish viewer of what piles up on top of him.

There's all the Evil Dead you're ever going to need here, assuming they don't make another.

Secrets of the Saqqara Tomb (2020)

Polishing to familiarity

The basic mode of Netflix, as I'm discovering lately, is a kind of softly produced cable TV with inclusive values. The target is a broad audience that a while ago would have simply watched what was on TV.

Here's the softening effect. In a documentary about important archeological discovery, we have lush, polished images of the interior of the tomb as if Russell Crowe was about to walk in for a scene. I miss an eye that actually discovers as they did, the awe of having a presence.

It's the same thrill that tickles archeologists the world over as they dig; not just acquiring knowledge of distant mores of life, the way a biologist would, but standing in the middle of tangible things that suggest world, broaden horizon. You'll notice this is a recurring fascination in the film. People really stood here, touched this, played this ancient board game that no one has touched for 4000 years. The mummy laying before us is an actual person from ancient Egypt. It' vividly shows how objects are enlivened by the world they suggest. So it defeats the whole point to give us images with the same feel as the movie version.

And this softening extends in how we come around to discover; we want to find out the 'story' behind this place, archeologists explain to us time and again. There are four burial shafts inside the tomb, and once we dig down to the bottom, we discover ordinary human beings who loved and suffered; an ailing father who probably had to bury his children. Instead I find myself captivated more by the notion of world these people inhabited, which is completely unlike ours today; the complete certainty of living in world that is just a first life that extends into next, a whole life building up to this rocketing of the body in the afterlife.

These are not just decorations on walls, one of the archeologists explains to us. They're 'dreams'. More akin to film than painting, I would add, how we peruse film. Will we ever again be able to be moved to such deep belief as these people? Rather than the overt familiarizing of whether or not someone died from malaria, or did they have lion cubs in Egypt, there's a more interesting one here about how we wave abstract worlds into being.

Come to Daddy (2019)

Slipping up

I've been on a prolonged hiatus of sorts. With lockdown looming once more around here, I figured a few horror films would be an undemanding return to viewing. It's that time of year anyway.

This one seemed to hold some promise among the few I've managed to see. Apparently some of the same people who made the lovely Housebound would be involved. It seemed that it might have some of that New Zealand spark which I love, usually a quaint neighborhood providing the room for slimy inventiveness.

They were probably aiming for something of the sort. A man travels to a remote cabin to meet his estranged father but once there, a trapdoor opens beneath our feet. It does have some of that irreverent tone, blood spatters in a few places. But it kind of limps along, over just as it would have to get going. You have to be carried outside story at some point with these, staging faster than we have time to catch our breath.

But it's an oddly fitting metaphor for the film that Elijah stumbles awkwardly through a story, always slipping up, never really improvising even when he does.

Arsenic and Old Lace (1944)

A critic's imagination intruding

There's a great film here but you'll have to dig down in the basement for it.

I saw this a few days after The Philadelphia Story and what a contrast they make. Both incidentally take place around a house. But that one stagy, sedate wit, pleasant in the way of a dinner engagement you'd rather skip. This one imaginative, uproarious, fluid in visual narrative, both in the short and the long form.

In the short this means a lot of gags and a constant zap of manic energy - no less from Cary Grant who gives a Bugs Bunny performance, a new slapstick expression every minute. Once more a house of fiction and games, by now a Capra staple. In Mr. Deeds and You Can't Take it with You, it was a house where in all the playing around and unexpected fooling with etiquette we could recognize the upending of boring normalcy. It's a bit different this time.

The playing around in this house is all about self-referential recognition of the absurdity of what we're watching. Fiction.

Grant for one plays a dramatic critic, someone whose job is to watch and criticize plays. One such play unfolds in the house all around him, and it's one that constantly opens trapdoors in what we expect to see. I will not spoil the main surprises.

This is one thing that's marvelous here. Having Grant (a rather smug fellow when we first see him) as viewer who is constantly bamboozled by what goes on around him.

The swirl of fiction about fiction also involves a passing cop on the beat who is an aspiring playwright. In another spot Grant describes a scene from a silly play he once had to see, one where a hapless victim agreed to be tied down to a chair by killers, and while demonstrating the scene he finds himself in the very same scene he's describing, tied to a chair by killers. Another scene has him watch from a staircase at a fistfight while commenting on the action.

There is a crazy nephew in the same house who thinks he's Teddy Roosevelt, dresses and performs the part and constantly charges up a staircase he thinks is San Juan hill. Teddy was probably still at this point the most iconic president anyone could remember. And of course famous for his blustering performances and a natural storyteller.

Another brother is made up to look like Karloff from Frankenstein and is recognized by everyone in the film as Karloff the actor. No accident. Karloff himself was playing this character on the stage but could not appear in the film version. I should say it's a pity we don't have him but Massey is superb and truly steals every scene he's in.

That's all fine. I adore visual imagination, the spontaneous and impromptu, the fooling with expectation. But Capra as so many times before misses in the long form; this is where what we see would begin to amount to real significance for someone who has a life in the story.

There was no filmmaker more capable at the time than Capra (and I think him immense in talent), who always comes so close but could hit so widely off the mark.

The long form here is that Grant is not just a critic, he's also a writer who's written a few books against marriage - but as the film begins has actually decided to marry his sweetheart. The film opens at the courthouse where he tries to marry while avoiding being recognized as the writer of those books.

So this should be against everything he's espoused so far, there has to be some unresolved tension in him. Note also that one his books is titled 'Mind over marriage', possibly implying a life of the mind and enjoyment of oneself is preferable. And how about his aunts commenting at one point that 'everyone is nervous when they get married'?

Here we see a narrator who has been attached to a story about how life should be, but now life and the vagaries of love capriciously upend it, showing to him how silly it has been.

So what happens in the film? No sooner is he back from the courthouse to his aunts' house who are preparing a wedding cake and a celebration than things start happening out of the blue.

Dead bodies suddenly abound, note, of lonely old men who had no family of their own. A brooding brother appears in the house (in the face of a famous cinematic monster no less), who has led the solitary life of a vagabond and has to change faces every so often, lost to himself.

Is it his own brooding self the one who subconsciously intrudes upon the house on the day of his wedding and is creating what we see? Marvelously these intrusions are in the form of self-referential bits from other plays and movies, a critic's imagination.

There are eventually too many shenanigans for this to shine clearly across the whole film, but you should definitely visit at some point.

Bluebeard's Eighth Wife (1938)

Continuous shift

Oh Lubitsch how we needed you. Others could elicit fiery performances from actors, captivate with riveting story or lavish us with sets and camera magic. These usually require to be propped up with some effort, but what Lubitsch does simply requires letting go of, in particular letting go of our need to prop up fiction a certain way.

Usually understood as a gift for wit, his famed 'Lubitsch touch' is actually a mastery of something else, spontaneous illogicality. I have written about him in a few other posts so will not bore you here. It's the continuous shift of context, the dismantling of our expectation that story plays out a certain way.

The story could be anything, here a man and woman court each other while vacationing in the French Riviera. He's the blustering American type who won't take no and won't tiptoe around European niceties. She's elegant and smart but will not stoop to be wowed by money like her shyster father.

In the usual mode, they would brush and bounce off each other whilst trying to top each other for control over the story. This as hardwon love that surprises. That's fine, plenty of enjoyable films were being made in this time, what we now know as screwball. For me it's all a matter of how we brush, how much narrative space the players create by pushing and pulling, in which self can take shape, actual visible shape, as the story we watch. Capra has a very agile touch in It Happened One Night. I happen to find His Girl Friday coarse, par the course for Hawks.

In Lubitsch's world, we shift and shift again in a jazz merry-go-round of elusive self. Here's some of it. They meet as strangers in a store, cooperating over trying to buy pyjamas. He decides he's smitten, but uses money to come close to her. So what happens? She agrees to be bought as a wife but gives him a thankless marriage for it, although in love herself.

This is lovely work, clean, vibrant. Some if are just gags, like having married seven times before her. But quite a bit of it is that wondrous surprise where emotions express themselves in paradoxical ways.

The Philadelphia Story (1940)

Stage strutting

This is too stagy for my taste, which makes some sense as it started life on the stage. It's witty, but not the crackling wit stitched from paradox that I get from Lubitsch, rather sedate. It takes place around this rich mansion, but it's not particularly invested in place, the way it is with Welles, or even Capra and Sturges.

The one attribute that makes it stand out is that this is a film about Hepburn stepping into a film so viewers can engage with what moves the icy, indomitable self.

She enters 'the Philadelphia story' knowing it is a story being prepared by nosy journalists who have come to get a scoop on her on the eve of her wedding, the story as the ensuing film.

Three men vie for her affections, each one offering up his own understanding of Hepburn.

Grant as the playboy ex-husband who left her muses that she has been acting the part of callous goddess while missing genuine heart in her performance. The second is her current beau who she is slated to marry the next day; he's entirely smitten with her goddess image and doesn't want her to change, but this understanding of her now appears to her trivial and callow, merely that of an admirer.

And third is Jimmy Stewart as the author who is there to jot down the story for the paper. He is the most suspicious of her wealth and vanity but getting to know her sees her as a radiant soul. The usual shuffling of screwball films ensues about what happened last night and who she's going to marry after all.

It's not particularly my kind of thing but there's obviously a wide audience of Hepburn lovers and fans of the era that will be more than happy with it.

Portrait de la jeune fille en feu (2019)

Embers of previous life

Is there a more vital subject than youth being ushered in the larger world? Whether it's Wong Kar Wai's take or Harmony Korine, I am rapt to receive them. Earlier still it was Rivette. A lot of film noir plays on the same impulse of discovery.

Being able to see with the urgent eyes of youth, it's more important in my book than the most lofty moral lesson. It's something I wish on all of us.

And tying this to image, the realization of constructed imagination, elevates this to something I want to pay serious attention to. Celine and Julie Go Boating, Chungking Express, Spring Breakers, each one toys with spontaneous discovery outside of fiction, performance that takes you outside performance. Each one ties that to staged image, fiction about escaping bounds of it.

So I am the target audience for this or should be.

And the main narrative device is lovely. A young woman arrives in a remote island, commissioned to paint the portrait of an elusive daughter who refuses to be painted. Sitting to be painted means the painting is going to be sent to a suitor waiting for her abroad.

There are a couple of decent performances, sure, and the setting with cliffs overlooking the wild sea is a wonderful stage. The air is one of expectant apprehension. Stolen glances. We just know sparks of passion are going to fly.

But watching this, I expect the air to catch on fire, the air around the edges of imagination. I expect passion to be the urge for deep communion and that to spring from air, not wholly known in advance. Isn't this after all a film about doing away with the accepted idea of how something ought to be? Indeed, how a portrait should be painted, which in the world of the film it's how love springs, or how life in the years ahead of youthful discovery is going to be. And this remains neat, tidy, arranged.

We know she can't stay on this island forever, that there is a next life for her. It's true for all of us. Is the Milanese suitor going to be the love of a lifetime? Would her painter friend be, if they were allowed? The tragedy here is that she may have found love but it can't be allowed.

Here of course it's not least because they're both women. But I would have you imagine the same film only the young painter is male. The same otherwise brief, ineffable love. He loses her. He paints her as he imagines her to be in that next life. He then watches her from afar as she cries inconsolably at the opera. Is she crying for lost happiness, as we're seeing her through the eyes of her past flame, or is it the opera? The shift now becomes a bit more clearly about obsessively holding onto story rather than just socially thwarted passion.

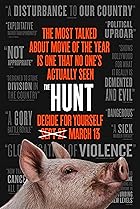

The Hunt (2020)

Kidnapped into story

This is a Battle Royale situation where the rich hunt the poor but with the added twist that it speaks about polarized America, liberal elites against Sean Hannity rednecks. Given the template, we know we are not going to have to really know any of these people except as fodder in a game we watch. Stereotypes are mined often. The tone is gleeful, poking fun in passing rather than overtly serious, and I would rather have it this way. It's a light-hearted jab at a really broken historical moment.

But as with other concept movies, after the raft of initial surprises of world are peeled off, I'm left with the same ordinary scenes of action, shootouts and fistfights. It trails off near the end, having nowhere left to go. The idea, spelled out for us at the end, is that the level of enmity and suspicion of the other runs so high, stories of how deplorable the other is give rise to the real thing. Both sides end up being kidnapped into the story.

Dark Waters (2019)

The moral upkeep of a house is vital work

I'm even more appreciative than in the past of films that inspire us to be alert citizens, given the work we have ahead of us. And this is simply important work that should play in every home. I'm baffled to not see it among this year's Oscar crop, it's the type of film that is usually acknowledged over there. No matter. Everyone involved here deserves applause.

It's a chemicals company being exposed this time, knowingly putting carcinogens in all of our homes and having covered it up for decades, but the gist of what matters is the same as every other time; people in high places lied, being negligent of human life, using layers of bureaucracy to hide away uncomfortable truth. Why care, really care, when studies can be stashed away, ignored for now, or responsibility passed along to some later committee, to be dealt with then? The good life of being a corporate executive is always enjoyed now and you are surrounded by its immediate benefits every day.

It's important to be able to parse with these that it's not some intrinsic evil at play but the mundane stuff of greed and ignorance, indifference to a world outside our narrow bubble of comfort. As the case picks up publicity, we go on to see scientists on the company's payroll and ordinary people against their neighbor for causing trouble to their biggest jobs provider, although they're all being slowly poisoned.

I've said it before, but what this world needs every time a scandal of this magnitude breaks out is deeply moral resolution. People really need to see in their living rooms news reports of CEOs arrested at home, trials where judges hand down life sentences, no ifs or buts. Not out of vindictiveness at rich guys, but out of moral urgency in the face of wrongdoing that is no longer allowed to be vague, or whisked from view behind legal settlements. The scale of wrongdoing here is so big we're really talking about crimes against humanity. We then wonder about populism and culture wars.

It's because we don't get that, that films like this are a last resort. Is there a more satisfying scene this year than the one where the boss of the law firm, just as we think he's going to side with caution and his corporate clients, hammers home the need to do what''s right?

This leads me to why this is rousing stuff in terms of mechanics of narrative, that is to say quite apart from the subject matter being worthy. It's not enough for the subject to be educative after all or for right to prevail eventually; we really need these to rouse us from our seat, dispel indifference.

The good guys here we understand have been all this time on the side of bad guys. They know them on a first name basis, hobnob with them in cocktail parties and industry conventions. They have defended them in court before. It's seeing them take up the case against their former clients that inspires.

Even so, our guy is working the case by himself, at first looked askance, merely tolerated. But just as we expect him to be eventually told off, ostracized, thwarted or fired, because of rattling important clients, he's allowed to go on. In the all important meeting to decide course of action, the boss is on his side. On opening day at court, he sits with colleagues who might never have bothered on their own, but there they are now with him, ready to defend right from wrong. Tacitly we understand that lawyerly knowledge that had been used to defend the bad guys, the reason there's so much contempt for the profession, is now going to be brought to bear for a just cause.

The big speech that in a Capra film would have been reserved for the end here takes place midway through - and is shown as being delivered to various people.

Among them are the company's executives who look glum and pensive, and this is where movies work. In a movie we can have the company executives look glum and pensive for us, coming to the realization that we would like them to.

This is worthy stuff, born from the same great American tradition in narrative exposition that has seen even presidents held accountable. For all the gross negligence of their corporate world, Americans have by far the strongest journalistic practice in the world. With all that's going on these days, it's heartening to be reminded.

Beoning (2018)

She comes back in another guise

There was Resnais early on, later Ruiz, Greenaway, and many others, from the Coens to Almodovar. The blueprint is by now familiar; a narrator who finds himself in a story that he gives rise to, funneling self into encounter and vice versa, and all sorts of elusive interplay between what is real and what is imagined.

Here we have it laid out early in a shy young guy, aspiring author who has not yet began to write but might be (knowingly or not) looking for a story, who one day chances upon a girl. She's bubbly, eager to know him, and holds a sense of mystery, someone who decides to just go off to Africa on her own, completely unlike his own inhibited self.

But having just met her and learned to pine for her, she disappears. Coming back from her exotic trip abroad, she disappears from him with a rich guy she met whilst there, someone who drives a Porche compared to his beat up lorry. This turn in the story makes her look superficial but we're dealing with impressionable 20 year olds here who are just setting out to explore in the bigy city.

So she disappears and he starts looking for her but that's now in ways that begin to amass a story around him. Is it the kind of story he was looking for? Later in the film we see him type in her apartment, now tidied up as his own place, which might always have been that.

And in this story that unfolds around her disappearance we have what? This mysterious rich kid who goes around burning greenhouses for no reason, reflecting a suave version of his father's anger, his father's anger perhaps tied to their abandonment by the mother. There's a vision that lights these up together, of a kid standing before a burning greenhouse. And lo - the mother now coming back to visit, and his promise to help her, with money that he doesn't have of course.

The most worthwhile parts of the film all revolve around the realization that here is a lonely boy, at a most sensitive time of his life who must face it alone, who might have just spurned the only person that would have been there for him. This is poignantly given in a brief exchange - insulting her for taking off her clothes, when she was really expressing melancholy joy in her dance, and is most likely as alone and fragile as he is, means she completely disappears from his life.

There is a lovely balancing demanded of us as viewers here that might go unnoticed and speaks about relationships in general, and who we are late at night; the girl did not promise to be the love of his life, you can never do that, and she was maybe not as pure and whole at just 20 years old as he might have dreamed (is anyone ever really?), but being there, persisting with getting to know her through turbulent self, she might have been the one to share that tender time of his life with, the time when you discover together.

So this is touching work about anxious youth trying to grasp life that I didn't expect to find tonight. Pantomimed urge in order for it to become real. My only caveats would have to do with missing a sense of genuine life, for example in how the girl enters his world - but it might be that we never really see her outside a story about the urge to find her.

The Lighthouse (2019)

Seabirds inland

This held such promise I am left wanting more than I get.

There is the potent sense of place for one, the windswept lighthouse on a remote island somewhere north that two men have been assigned to operate. Relief is weeks away, it's going to be just the two of them tending to the light on this rock in the middle of nowhere. We get the promise of drab work and chilly nights ahead.

There is the notion of virulent conflict. Down below is the lowly janitor, tending to a list of menial chores his overseer has just barked in the morning, scrubbing floors, cleaning the cistern. Up above is this capricious old man, who alone tends to the light that he sees as exclusively his and seems to be strangely in its thrall.

Even better, the notion that neither of the two men is quite who they present as. Over the course of drunken nights, we come to realize they're both hiding something. Along the way we have mysterious goings-on around the lighthouse.

So with no one set to come for weeks, with wind and rain fluttering outside and the sense of harbored secrets, we reach that razor sharp edge where the two of them grow unhinged in close quarters. Usually I'm not a big fan of current films in black and white, the sense that it's just a fashion reference to film lore, but it's ideal here.

But then it slips from them and just smears with the material. We get a hodge podge of visions, some of these ignited by guilt gnawing inside, others by magical belief tied to suspicion, still others by real discovery. The sophomoric ending with a promethean reach for the light is a complete wash, rather than opening up to vastness of self, it reduces to silly notation.

The most interesting thing for me here, quite apart from everything else, is the notion of capricious narrators erupting in whimsical performance. There is song and dance, and even a threatened kiss that is interrupted by fisticuffs. Dafoe is just spectacular and his snarled curse because his cooking has been slighted has to be experienced. I'm just beaming at how he gives himself to this role.

Although I leave wanting more, I think film this year is richer for having this film than not. I would like to see how this guy evolves, it's still early. It took Wes Anderson twenty years and many tries, so why not him?

But meanwhile, have you seen By the Law from 1926? A log cabin in the snow instead of a lighthouse, but also madness seeping in with the rain, done with the assured hand of someone who knows how mind can change the weather.

Logan (2017)

Different ways to give rise to world

I admit I was taken aback with this one. I hadn't planned on watching as Wolverine films tend to be a bore to me. Not long into it, I was sure I had missed a previous film, one that would explain for example how Xavier ended up broken and hidden away, how Wolverine has washed up as an alcoholic limo driver.

But no this is it apparently, and this is the thing.

We can be lowered late at night in the middle of a world that has long now been spun in motion. We can discover as we go. We can catch glimpses of a larger world as we move through it. We don't need to be racing to save the world, making it out of this room alive is enough, wondering and having no idea where to turn to next are fine.

None of it is novel, in fact all of them mainstays of 80s film, from Bladerunner to Terminator. But after a glut of samey, mechanized Marvel and X- men movies obsessed with 'universing' a greater story, this one feels welcome and fresh.

Another obvious influence here are western films and this probably sheds some light on Wolverine's popularity. So many of the other X-men have awesome abilities to alter the fabric of reality; Wolverine is just a gruff who kicks and punches his way through. It seems there's always going to be a hankering for the simple, uncomplicated guy.

So what more obvious choice than to cast him in the light of cowboy? It works but you'll note it's not any cowboy. They could have used Red River as template, or The Searchers. They used Shane. The flawed guy who risks all to ensure there are 'no more guns in the valley' but must ride off again at the end because his kind has no place in the world of loving farmsteads.

It's always indicative of a broader sensibility when I see this type being used, the resignation that someone has no place in a changing world and is better off being swept away with the old, this seen as 'honorable' and heroic.

But from the little girl (and her friends') point-of- view we have what? A fictional Eden they only knew as stories in a book but their desire for it has inspired an actual one.

Hell or High Water (2016)

Emotive clutching

You know the kind of film this is. Border crime, terse visuals, sudden violence, melancholy prairie. Texans in stetson hats ride muscle cars instead of horses but it's still very much a western that we see. We still have the grizzly old sheriff in pursuit of bank robbers (and being casually racist to his Indian deputy). We have a posse of townsfolk giving chase, in SUVs nowadays. The notion that the two outlaw brothers aren't all bad, they do what they do to save their momma's ranch from the paws of greedy bankers.

And as customary in westerns the last fifty years we have all of this tied to the passing of the West. The tone is elegiac. We stop to see cowhands in horseback rustling a herd away from a prairie fire that no one is bothering to put out, it will simply burn down to the river. The small towns we see along the way look decrepit, a far cry from their Roy Rogers days.

It's not a completely wistful take. The Indian deputy reminds us that this was all someone else's smalltown America before you people came along. But as plaintive music now and then swells over shots of dusky prairie, the fundamental point here is a sense of inadvertent loss.

The notion is that America is no longer great; that some essential purity of America is gone. Bankers took it away. Huge swathes of the country would agree of course; it's a fitting western for the Trump years, meant broadly. It would have been written and began production long before Trump came along on the back of outrage.

It's what has come to be the worldview of the modern western, fueled by angst, fatalism and resignation to the passing of a way of life. Any worldview that laments change and looks back with nostalgic attachment to some purer past has no place in my home. But here's the cinch. These people would not look at their muscle cars and gas-guzzling SUVs, or TVs and cell phones, as part of modern change that sweeps away a way of life. They would not bat an eye at rock bars or getting a tattoo, which their grandfathers would have found abhorrent.

In the western (both as film and mentality) so many things can change in other words, except the notion that a purer way of life is being swept. It's interesting to note that out of the many possible threads of what the western could mean, it has been reduced to this. What would it be like for example for modern westerns to celebrate the resilience of community, or the joy of banding together for common work? Sulking is a powerful impulse.

Roma città aperta (1945)

Stagecraft

This is such an important work even the Vatican now includes it in its list of great films (no doubt for the self-sacrificing priest). It features in sundry other lists, an obligatory stop it would seem for anyone wanting to sample the works that defined film.

By now you know it as a classic that heralded a whole new mode of filmmaking in Italy and abroad, more 'real' and immediate than the studio artifice of before, taking place in open streets, using non-actors, relying more on improvisation than script. Sitting down to watch this now however, you'll be confronted with something quite melodramatic, scripted and acted in the usual way. An early scene for example where people ransack a baker's shop for food you'll be able to tell as the scripted dramatization of food shortages rather than something that can steal into you as visceral and improvised. By this I mean the whole stagecraft is obvious and doesn't feel all that different from a studio movie.

In spite of some of Rossellini's efforts, our distance from these Rome streets where real people were suffering only months before through events much like we see in the film is simply not as close as you would perhaps expect.

In part that's because our own viewing has shifted since. WWII movies are now common film lore. This was the first of its kind, if we exclude documentaries during the war or jingoist propaganda. Work began only months after actual Nazis had been evacuated from these same streets. War was still booming elsewhere in Europe.

But even more important for me, I don't think Rossellini was setting out to revolutionize. Realism in this case meant chronicling very close to real events rather than a radically 'real' light in which to do so. The urgency of the effort would have been enough to deal with I'm sure.

It's this urgency to stage events so close in time that inadvertently becomes mirrored in the film itself. This, rather than a story of defiance against Nazil evil, now seeming ordinary and usual because of how familiar, is what I find the most vital thing here.

The film is about rival groups trying to stage events and assert control over them around the city. Members of the resistance sneak from house to house trying to evade capture. Meanwhile the Gestapo is scouring the city for them.

The first have to spontaneously improvise on the spot, make narrow escapes, act roles and create fiction around the authorities. The Germans are rigidly controlled by a Nazi director who never leaves his office. It takes a spurned lover, judging her for how she lives, to give them away.

There are of course scenes that still affect. The one that begins with Nazis rounding up of tenants from a tenement and ends with Anna Magnani chasing after a truck would be my favorite here. The ending with a prisoner being tortured to confess must have been a powerful depiction at the time, but it's also part of a melodramatic climax.

Senso (1954)

Opera house, pamphlets raining down

Italy is still probably in ruins of war at this point, real or figurative, so what does this filmmaker do, Visconti? By waving his wand, he conjures up an earlier Italy, also in the throes of occupation and war, it's the last days of the Austrian occupation around Venice, but now it can all be placed in the safer distance of history, set up as operatic melodrama on a stage.

You'll see this self-referential waving of the hand in the just the opening scene. We open in an opera house in the middle of a play, with actors on stage valiantly rushing to weapons. As soon as the play is over, patriot viewers rain the place down with revolutionary pamphlets.

It is an operatic play that we see; film as opera. Up on this stage, collaboration with a regime can be safely contained in a love affair, rich countess falling for the dashing Austrian lieutenant. In the usual melodramatic passion, she risks all. The whole point of the story is to have moments like when news reach her of a battle won against the Austrians, but instead of rejoicing at liberation, she must look terrified because her beau might have been on that battlefield.

It's not something I can get excited about, nor would I recommend you go out of your way to find it, except as contrast to other, more pertinent things about how a viewer can be choreographed through space. I mean, here is a cinema of vistas and gestures. When a camera pans around a room that someone walks in, it's just this room that we see. War is suddenly introduced as a series of vistas with crowds rushing about, filmed in a disjointed way in order to convey chaos and mobilization and yet they manage to look placid and painterly.

But how about this? It ends with another self-referential note but now one that waves away illusion, dispels fiction. Having risked all, she finds out he's not the dashing hero of operas that she wanted him to be.

Up on this stage, turning your back on your countrymen is only the innocent fallout of passion, all because you maybe yearned for some of the romance of stories from the past.

Beyond the Forest (1949)

Scoffing at the role handed you

This is utter schlock that wouldn't look out of place in a marathon of bad movies. Here are a few pointers as to how outdated. A moralist intertitle announcing we're going to see a film about naked evil. Religious King Vidor at the helm. Omniscient narrator hovers around town setting up the story.

But this is Bette's show as well. Reportedly she was disdainful of the script and tried to walk out several times. I don't know if you can tell by watching that she hates it, the Bette Davis devout might, I haven't had the chance to watch her in a while. She's always so eminently watchable however and no less here, sneering and scoffing her way through the role of contemptible manipulatrix tormenting her milquetoast doctor husband.

She is the 'evil' of the intertile, her naked lust for money, her haughty ego that she's too good for the small Wisconsin town. Her burning desire and ego are visually exemplified in the fire of a nearby sawmill that burns through the night, visible from her window. She writhes and winces a lot, a picture of someone completely at odds with themselves. In a most heinous moment of the story, she calls in her husband's medical debts from the poor workers in town, all so she can go to Chicago to buy clothes. Once there she hopes to elope with a rich guy.

It's all as incorrigible as this. But this is Bette's show, which means a struggle with the fire that burns inside of you, a struggle to harness explosive talent. What does this mean?

This is the film where she famously says 'what a dump'. A more fiery moment however for me is when she demands from the rich guy to marry her. She wants out of the dump badly. Rich guy raucously laughs and points at her, laughing. Is Bette phased at all? She crosses the room and slaps him, hard, and cut to her looking triumphant. He kisses her.

The film is about a headstrong woman who is unhappy with where she is in life. Written as it is, by some guy in the 40s, the film goes out of its way to portray her as truly vile; not just an unhappy wife but unhappy because she can't buy nice shoes and clothes. Fierce but deliberately shown as idle and superficial. But what if we decide to not settle for the cartoon manipulatrix grafted on top of the unhappy woman and instead see someone who wants out from a role she has been squeezed into?

Being a headstrong woman who wants to be in control of her own choices was enough to label you spoiled and ungrateful in the 40s. Bette knew first hand.

Pitfall (1948)

Washing up in dreams

With film noir we arrive at a crucial junction where the old certainties just won't do. A world war had intervened, with home deeply upended for a few years, or permanently in many cases. Men and women had been plucked from normalcy and sent away to new unexpected lives.

The American experience of the war differs in an important way. The whole world is disheveled in the chaos of the ordeal, chaos which from the American perspective would have been not without excitement at being part of a collective purposes; a joyous sense of riding to the world's aid, knowing one day soon it would end. But crucially, at the end American homes are where people left them. As a bonus, the Depression has magically gone away, wiping clear the horizon.

So once you return, the world proves to be a disorienting thing, must have been felt to be. Having seen it all become uprooted and airborne, are you supposed to go back to being content with a home and a job you went to?

Tonight I can think of no better entry into the floating dream world of noir than this small film here, none, and I put it above many of the famous ones. It's part of a few Lizabeth Scott noirs she did in the brief time she managed to land roles. An interesting thought I read, she may have managed to squeeze in (along with others) while more established actors were busy with the war.

At any rate, I find myself wholly captivated by her this past week. I think she's someone truly worth knowing, and being able to see her in the context provided by films like this one and Too Late for Tears, just these two are enough. The closest parallel I can think of is Gena Rowlands; the same unaffected beauty; the same hardness around the eyes and smile that cannot conceal hurt; the same sense of a tough broad who knows how to survive and how to be on her own. Lizabeth must have been a tough cookie and although it seems she was wasted in some conventional roles, the material here was just right for her.

This is about everything just said above, the dreamlike tiptoeing out of the loving home of stability, someone nagged by the sense that out there in the city another life could be lived.

With just a few brushstrokes in the opening scenes, we get the illusion that becomes our space for meditation. The perfect American home somewhere in postwar Los Angeles, the wife has just finished cooking breakfast, the husband is getting ready for work. They're not rich but they're comfortably middle-class.

In a marvelous scene while she drives him to work, he wearily wonders if this is all life is going to be. He muses about just keep driving to South America together. It's great to be able to see in these exchanges not some feverish desire, he knows no one is going to be going off to South America or quitting his job, but a quiet and more everyday dissatisfaction, one that underpins so much of modern life.

In this ordinary insurance guy we can see one of those people who were whisked away by the war and returned to probably the same life after. It doesn't even have to be gruesome war in Okinawa or Omaha beach, in his case he was safely stationed in Denver, Colorado.

Another marvelous aside is the notion throughout the film that kids 'these days' have it easy. Trying to read to his son from an old book about western adventures, the kid obviously prefers his stash of comic-books with alien monsters. The kid may have grown up to be an old man musing about how hard they had it in the old days.

This is what's so great to see here, our placement in ordinary life that in many ways continues unabated. He does meet a beautiful woman later that day, he has gone to her place in his menial role as insurance agent. They take a liking to each other. Being with her promises another kind of life where you can just go on a boat-ride and stop for a drink at midday. But she's not some scheming dame, just a working class gal. Their affair is not riproaring passion that turns the soul upside down but a brief dalliance of quiet affection, maybe even just this one kiss we see.

Of course In the dreamlike world of noir machinations have already been set in motion, I will leave you to see what happens. But once more, nothing far-fetched, the sense is that life can just heave this way or that over the course of a few days, ordinary life full of paradox and coincidence. What does kissing another woman one harmless afternoon mean? It means someone is waiting outside your house one night.

This is potent work, rife for meditation, all about slow days that look the same and the wider horizon. The mind sees pictures all day and night long, he explains to his son who is startled by a bad dream. At night some of these pictures wash up in dreams.

Desert Fury (1947)

Yearnings, thwarted

As far as Hollywood quickies go this is full of hysterical verve as another reviewer aptly points out. It's billed as film noir on here and that's how I came to it but it's not, it's romantic soap opera.

Its first of two real charms is the lush Technicolor, that always gasp-worthy window into a world of splashy color and make-believe light. I've never seen a color film noir that lets us take in the city; whenever producers decided to splurge for it in this milieu, it seems like it needed to have a pastoral desert background, pristine skies in the distance, Nevada here.

Its other charm and probably the real reason you might decide to visit is the story of rebellious young daughter falling for the gangster bad boy in the rural small town. This is against her mother's warnings and really the warnings of every mother in the audience.

He spits insults to anyone who might tell him what to do, she won't stand for her mother's attempts to tell her how to live her life. Both are fresh back in town, both fret with the limits of the established smalltown order. Hodiak and Scott are both superb. We get the sense that in spite of everyone's warnings, she'd jump in his car in a heartbeat to go to LA.

Interesting to note here that the idyllic desert of westerns in her case means a narrative of being married to the good, sturdy guy and settling down together in a ranch, but through her eyes this is seen as stifling. In the usual mode Lancaster would have been the hero and romantic interest, their love would have been thwarted because he doesn't have any prospects.

It's a Bonnie and Clyde origins story, the same story that would resurface in countless other films from Gun Crazy to Badlands. With a temper like his, we get the sense that it would not take much for him to leave dead bodies behind and it would not take much for her to accept it as part of furious passion that rages against the world.

Eventually she does jump in his car and they're off to LA, having spurned her mother. Badlands would go on to give us the violent spree and poetic journey.

Here we are turned back on the road. This is shown as previous life catching up with them. In a diner an odd bit of psychology takes place where he's revealed as never having been the flippant, cocksure guy she was attracted to but an actor strutting on a stage others had prepared for him. The film accepts this as the final verdict, because in spite of everything just seen, we really need her to be back home to reconcile with her mother. In the end she looks over the desert at sunset with the good, sturdy guy, pining for that ranch together.

It's not even the sermonizing type; her mother is portrayed as someone who has known danger and passion like she wants to indulge and came out tired but on her feet There's a youthful yearning here to burst out from the idyll of rural America into dizzying modern life. It wasn't yet time but that would come.

Road House (1948)

Ida's free and easy swim in sultry noir

This is made with enough memorable pieces - the 'road house' in the small Midwest town, the torch singer fresh from Chicago who comes to upset the sleepy routine, the two men, owner and manager of the joint, who lust after her - that it would have been something to see regardless of who was in it.

Someone like Gene Tierney or Rita Hayworth would have been equal parts fierce and coquettish in navigating their private wants against the male desire that threatens to create a narrative that engulfs them. That would have been fine and the film worth watching.

But we got Ida Lupino instead, that whirlwind of softly indomitable spirit. I had heard enough about her in my various travels through film, always in context of trailblazing individualism, and have even seen her in a couple of films before. But for whatever reason, this was the first time I was so profoundly captivated by her talent that from now on, she's forever celebrated in my house.

Going by what she achieves here, she should be rightfully mentioned on par with Cagney, that other whirlwind of intelligent presence. It's an ability to float past obvious limits of a narrative, and from there inhabit a self who can freely enter the story, play and improvise on that edge, that makes her unerringly modern. In this case she gives us the soulful ingenue, the one required by the story, but at her choosing, and the next morning freely becomes someone who just wants to look around and explore.

Just look how her ability to shift what she inhabits in an easy and free manner makes the whole context of a scene shift. The scene with going up to the pond for a swim is written for her character to impress Wilde's as not just a stuck-up singer from Chicago. But the way she plays it turns it into she's there for a swim and shucks if he's impressed. Maybe she likes him, but she'll be fine either way.

She's so marvelous in the first half of this (which is largely devoted to her and her romance), you forget you're watching a film noir of the time. It's like watching an actor from 20 years later, a Nouvelle Vague woman. She manages to make the whole transcend and had me feeling what it would be like if more studio pictures of the time were allowed to simply follow along with contemporary life on the streets. We'd have to wait for Cassavetes to start that ball rolling and then onwards to Altman and the others. Ida would have made a dreamy collaborator in those years and would have flourished and shined all the more as both actor and filmmaker.

But this is still a film noir, which means succumbing to narrative controlled by selfish desire. In this case Richard Widmark is not happy that she chose his helping hand around the club; so he conspires to create a vengeful narrative that entraps all three, and no less his own self. The setting for this part is a remote cabin in the woods.

In a great scene the two lovers, looking glum now, sit across the table from each other overseen by Widmark at the head, as if the whole world has shifted to something other than real. Widmark, that early Jack Nicholson of film, deserves a standing ovation himself for all he achieved; not once has his usual mode of seething, petulant menace failed to enhance a film all the more.

The resolutions are predictable and really the last part of of the film is, but it's still decent noir. Taken as a whole, it's a rich primary text and wholly deserves the visit.

Nora Prentiss (1947)

The illusory nature of self

In the sweepstakes of film noir bleakness this one just breaks the meter, I'll have you know right off the start. It's pitch black and can snuff the light out of your whole day.

It's also one of the most overwrought, which means that the several changes of story give us a kind of life that teeters on the edge of the believable and more on the side of cautionary fable. No one leaving the theater would be anything less than smacked in the face with the moral downfall of a man led astray by desire.

But set that aside and you'll see here some penetrating notation on the illusory nature of self.

It starts the way it usually does, perfectly upstanding family man chances to meet a woman one night. His previous life of being always punctually on time at the office and back home again for dinner with the family suddenly seems stifling in light of the excitement that being with her promises.

This desire for escape from humdrum routine is given to us visually in a drive with her to his cabin up to the mountains. A place of seclusion that is gathering dust because no one in the family wants to go there with him. He plays the piano for her, which he hadn't done in a long time.

So what does he do? He dies and disappears in a next life with her. How this is accomplished is one of those far-fetched changes of plot I was talking about that you'll just have to accept was the best solution that came to mind that night. But it's one of those masterful turns that film noir takes, suggestive of an illusory world and malleable self subject to capricious urge. I love everything about this shift, those anxious preparations to sail out of San Francisco, the notion that back home the wife had come to realize it had been tough on him.

So, in New York now everything ought to have been just the way he craved it. Away from routine that stifles the soul, alone with her, finally free to explore.

Except having disappeared the way he did, having shed the identity, he can no longer be the same person. He cannot take up his old practice again to make a living and even has to avoid anyone who might know him from that previous life.

This shift is one of the most startling depictions of desire, and can really jolt you if you watch with attention. It's not that we simply crave after things, that we get or not, and might be led astray in some vague moral sense or not. You'll see here how it hollows out the world, makes it concave. How, having traded away one life governed by more or less the same narrative but playing against a backdrop of implicit freedom, he finds himself in one where he's now prisoner of a meaningless freedom, no closer to the fulfillment he imagined.

Secluded in a hotel room, things grow unhinged, and there is more to glean here. It's not that he can't go out, he's perfectly free to. It's that, without the context of a larger life in which we come together, share talents, and see eaech other in the light of shared narrative, does it matter if he does? He's still (presumably) the same body, mind, personality, so what has been swept aside? Context.

The last part of the film is where it all unravels, therefore the most grotesque. There's growing anger and resentment between them. Our man is heavily made up now to look baleful and unkempt, a pathetic figure like out of a horror movie.

And then in another shift of story that you'll just have to buy, he finds himself back in that San Francisco life he left behind, only now he's recognized by no one and he's already dead in it. We have complete dissolution.

Pitch black but worth your while.

Force of Evil (1948)

Community fraying

This is a change of pace from the norm of film noir. Film noir of course is a varied group of films and there is no one way to do it, certainly not a right one. It was tracing illusory and disorienting existence in the big city after all, itself fluid and malleable, and that's what we get here.

But a few differences help cast a light on what this is:

- the protagonist is not a gumshoe unraveling a case or hapless schmuck crushed by the fates. He's a cocky narrator, as much in control of what happens as anyone else, and in on it from the start. He has the usual fast-talking bravado, he glides smoothly, sweeps the girl off her feet. And yet his real impetus is wanting to pay back a big brother who sacrificed to get him out of tenement life.

- the girl is not some world-savvy dame but a sweet, innocent soul who instinctively backs out of the racket when it starts to feel wrong and is ready to fall for him only tentatively, guarding herself as she gives way.

All through this New York looks gritty rather than sultry, the narrative light is harsh and anxious. The contrast is between not entirely legal but not entirely immoral slum life, and the new cut-throat world of big business coming for the little guy. It's a bit of stretch to show the smalltime hustlers as the personable 'good guys' but that's the short-hand used. Its real progenitors are gangster films.

- And third, there is a scheme underway that resolves all this, to turn a numbers racket run piecemeal from tenement backrooms into a respectable, lucrative business run from Wall Street.

There's a lot of talk throughout, in that rat-tat-tat fashion of Hollywood. The dialogue verges on histrionic, and the whole has a verbose feel, but one that feels like someone has studied this life and is trying to come back with an honest depiction. It has a thickness of world to it, although the mannerisms are obvious.

Here's the cinch and what probably earned the movie a reputation as left-wing and landed the filmmaker in the famous HUAC blacklist.

The scheme works, the older brother eventually goes along with it, who had earlier made a big moral stand against it. The girl is swept off her feet. Our guy stands to make a fortune, help his brother, and get the girl who is not a dame like his boss's wife.

Except, in unchecked capitalism no one is really in control. Police had been watching but it's the nerve-wracked bookkeeper who sets the scene for grievous consequences to follow. The moral resolution is that it works but at what price to the soul; the lesson remains that a life of scheming doesn't pay and I'm not bowled over in this case.

Even more pertinently however, were the smalltime hustlers a boon to their community? They were running much the same lottery, working peoples' money for the promise that maybe this week it'll be you. But it seems there were bonds of community which the merger frays and disturbs. You'll see that it's our hero's tie to a human story rooted in community that really foils the plan.

The evocative finale with the couple descending stairs with the Brooklyn Bridge hulking above them is a favorite. In fact my favorite bits here all revolve around these two and their unlikely bond, their playful interplay against the larger background.

The Two Mrs. Carrolls (1947)

Clumsy madness

Another noir with Bogart in the lead, here in the role of American painter who marries a rich English woman. He plays it his way of course, scruffy and hard-nosed, always on the edge of being abusive, and this is the main tension here.

It starts with him wanting to leave one marriage for another. We assume he's been swept by newfound love, the kind that maybe has come a bit late but here it is at last and tough choices have to be made back home. Except no sooner are the two illicit lovers back from their tryst than it starts to devolve. Instead of getting a divorce, poison is procured from a shop.

The shift is made, from temptation and how it weighs on the conscience, to overt and blatant evil. About halfway through, he has turned into a complete villain, Bogart excels in the malicious role, and Stanwyck is her own sublime self, fresh and gently spirited whilst in love but losing her grip in the house as her partner does.

The most interesting bits all revolve around Stanwyck in this house, a spacious mansion in the countryside, as she begins to piece the story and come to realizations. Wind blows all through the night, church bells chime in the distance. The center piece is a game of cat-and-mouse around the house in the middle of the night that plays like in a horror movie and there's a scene where Bogie is unveiled standing before an open window that shows he could have made a marvelous Dracula.

But the point remains, that it makes a very thin sense to have Bogie's character the way we do and the clumsy attempts to explain him (artistic madness) are no better.

See, the greatest attribute of noir is that desire may sneak up on you or me and a small slip that seemed not that big a deal in the moment can have cosmic repercussions down the line. It's the notion that taking this money, or sleeping with that other woman, can maybe go unseen this one time. It's why noir exists in the first place and is so deeply entwined with life in the big city; one rife with opportunities for hidden self and multiple lives, for both good and ill. That's a story for another day but the gist of it is, the noir protagonist is a schmuck, not a villain. It might be all his own doing, and some noirs make the moral point less stridently than others, but we can buy that we could be him on a bad day.

Nora Prentiss, another noir from the same year that I saw together with this, also goes far in how it twists and turns. But the slip into desire is so well handled, it's easy to accept that part. I have seen my share of film noir and would advise you to skip this one.

Somewhere in the Night (1946)

Renovated house

I'm a bit disappointed that I don't find myself liking this more than I do. See, it has one of those dreamy film noir openings, a man emerges from the war unable to remember who he is. Bandaged up in a hospital bed in Hawaii, it's still the Pacific Theater with the war in its closing days, he discovers a letter in his wallet but instead of kind words from a loved one anxiously awaiting for him to come back, it tells him he's loathed and despised. Deciding he doesn't want to find out who he was in that past life, he checks out of hospital without a word.

It's the stuff noir heaven is made of, the notion of a previous life and being karmically reborn into a next one, night in the big city rife with hidden knowledge, demanding we investigate. Coming back to a Los Angeles hotel that was his last known residence before the war, he discovers a satchel he had checked in, and lo, there's a note inside, and one that tells him he was paid a hefty amount of money.

At so many points sparks threaten to fly, evocative places are visited in the middle of the night, portentous characters are looking for him around town. He's beaten up, nearly run over, framed for murder. In the docks he meets with a wily narrator - a pretend spiritualist - who openly tells him he should not trust a word he says. There is another house where a spinster daughter makes as if she knows him but does she? A visit in a sanatorium reveals someone else who is locked up, unable to remember.

So much ought to have been just right here, making this worthy of other entries in my list of top noirs, and yet the best quality of films like Crossfire or Out of the Past is that they are able to ski on the edges of semiconscious knowledge, of self unexpectedly slipping into a world he gives rise to. Here we have a self-conscious filmmaker in control, who, it gradually becomes apparent, is trying to construct that noir sense. Instead of spontaneously slipping out through back roads, we're taken places that someone has just finished renovating for us.

It's the difference between detective fiction of the Sherlock Holmes kind and film noir where a narrator is not fully in control. So of course it all ends with the bad guy finally unmasking himself and making a big fuss of explaining things to us. Of course it's timed just right for the cop to make the arrest.

It's all a bit cleverly here, self-conscious, and you'll see it in the self-referential nod to movies. The same filmmaker would go on to do All About Eve.

The more tantalizing notion in all this for me is that the note professing such hatred for him really was from a loved one he stood up one day, or was it a last letter that he wrote and was planning to send but never got around to?

Julieta (2016)

Tumultuous sea out the window

My interest in Almodovar is rather muted. He doesn't excel in any of the ways of presenting the world that really matter to me but he does several things more than well, so every so often I visit. There is the desire to submerge ourselves in fiction, lose ourselves to self in order to wake to a fabric that extends from self. That's Talk to Her for me.

But like Woody Allen or the Coens, he has consistently worked for so long on the same motifs that coming to him is also a matter of is he particularly inspired that day. I'm pleased to say he is.

In the individual pieces of cinematic craft, this is not particularly exceptional. If you're heavily inclined to how story resolves drama, you will see here something that simply trails off near the end. The symbolic motifs greet us upfront; a deer in slow-motion, tumultuous sea out the window. His bright reds on walls and the like are not something I can get excited about, in this or any film.

But he is inspired today on the fundamental matter of self passing through self. He manages to do this with just a few strands of narrative. There is the young woman who was on her way to all life ahead of her that night on the train, who finds herself yanked by unexpected passion. There is the house of passion in the small fishing village, eerily explored with Hitchcock hues. And there is bewildering loss as she wanders away a widowed mother.

Above all I love here the sense of transition. Almodovar does so well - his actress helps - in spinning narrative to explore tragedy. He says enough about the jittery urge for adventure as a story we throw ourselves in so that we can infer more fleeting illusion around the crushing melodrama about life breaking down. She's not just this grieving woman that another film, say, in the realist format would have simply followed around Madrid; we're privy to all this richness of her young self having set off in search. Things couldn't have only worked this way for her, it's important to see; but sometimes they do, sometimes setting out for open sea means finding yourself marooned on an island, nothing right or wrong.

And Almodovar is ineluctably Spanish, meaning Catholic; so communion with the fleeting, transcendent stuff must take place firmly within ritual, in his case (just like Ruiz before) fiction. The whole is narrated by an author writing the story down as she waits in her apartment, shifting us forward and back. It speaks about the imaginative mind being burdened by the narratives of memory. For Almodovar, there is merit in the effort. Had she not stayed behind to write, she would have missed the letter. Even more pertinently for me, there is a bedridden mother (a mirrored woman) who is allowed to languish in her room, written off as an invalid. But when her daughter comes to visit, the recognition nourishes her back to her feet.

Carol (2015)

No arriving without going out

This is one to bask in its air for a while, one of several films about transition in life that I've seen in the last few days. It does not ask particularly difficult questions, about love or otherwise. Being able to inhabit transition is still one of the most illuminating uses of our time however. Going out the door, arriving at the last bend of the road before our destination; these are the stuff that make life the awe-inspiring journey it is, worth experiencing.

The double perspective we are offered here is on one hand a quarrelsome world of need and anxiety, a bit cold, with boys pressuring the young woman for her affections, trying to pin her down to a life. Eventually it's revealed to be a much more cruel place, its machinery extending far afield. A private detective with them all this time and having set up his filming operation right next door to the lovers' room.

But there's also the world of going out the door in jittery search; the world of tentative lovers getting to pull back the covers of self from each other. This is a world where taking images (the young one is a budding photographer) doesn't come with a narrative of what they can be used to prove or exact from someone (a trial about custody is looming), they are not 'taken' from, they are shared back in the open for what they signify; people having come close for the occasion.

Seeing is central here, the story is after all in Anna Karenina's lineage (a preeminent story where seeing gives rise to the world of urge). We've just described two different kinds of it; one seeing that is strident and anxious with need, another where the gaze is open and jittery with anticipation.

The gaze of the film itself is soft and languid. It felt like a more robust Wong Kar Wai. There is a marvelous tone poem the filmmaker squeezes in early, reminiscent of Kar Wai's going through tunnels. How exciting to consider that what would have been experimental film in the 1950s, now is part of the common fabric of perceiving. The whole production also deserves a mention; bringing the era alive must have been such painstaking work. They do it, creating a 1950s world that envelops while avoiding the stifling impulse to see 'period' in purely sumptuous terms of a rosy past. I left the film with a sense of Roonie's character as a young student discovering life just like someone would now.

But there is also a third seeing that I would remiss in failing to mention. See, there is going out the door, and there is arriving on the last bend of the road, maybe the one before last. There is discovery and there is how to move forward from it. It's what we have in the final shot. Is she there to say goodbye the way they both deserve? There to announce she's there?

As with the whole, it's not something we've not seen before but I like the things that we are called to inhabit here.