Plutonium(IV) oxide, or plutonia, is a chemical compound with the formula PuO2. This high melting-point solid is a principal compound of plutonium. It can vary in color from yellow to olive green, depending on the particle size, temperature and method of production.[2]

| |

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| IUPAC name

Plutonium(IV) oxide

| |

| Systematic IUPAC name

Plutonium(4+) oxide | |

| Other names

Plutonium dioxide

| |

| Identifiers | |

3D model (JSmol)

|

|

| ChemSpider | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.031.840 |

| EC Number |

|

PubChem CID

|

|

CompTox Dashboard (EPA)

|

|

| |

| |

| Properties | |

| O2Pu | |

| Molar mass | 276 g·mol−1 |

| Appearance | Dark yellow crystals |

| Density | 11.5 g cm−3 |

| Melting point | 2,744 °C (4,971 °F; 3,017 K) |

| Boiling point | 2,800 °C (5,070 °F; 3,070 K) |

| Structure | |

| Fluorite (cubic), cF12 | |

| Fm3m, No. 225 | |

a = 539.5 pm[1]

| |

| Tetrahedral (O2−); cubic (PuIV) | |

| Hazards | |

| Occupational safety and health (OHS/OSH): | |

Main hazards

|

Radioactive |

| NFPA 704 (fire diamond) | |

| Flash point | non-flammable |

| Related compounds | |

Other cations

|

Uranium(IV) oxide Neptunium(IV) oxide Americium(IV) oxide |

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa).

| |

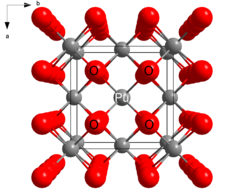

Structure

editPuO2 crystallizes in the fluorite motif, with the Pu4+ centers organized in a face-centered cubic array and oxide ions occupying tetrahedral holes.[3] PuO2 owes its utility as a nuclear fuel to the fact that vacancies in the octahedral holes allows room for fission products. In nuclear fission, one atom of plutonium splits into two. The vacancy of the octahedral holes provides room for the new product and allows the PuO2 monolith to retain its structural integrity.[citation needed]

At high temperatures PuO2 tends to lose oxygen, becoming sub-stoichiometric PuO2-x, with the introduction of lower valence Pu3+. This continues into the molten liquid state where the local Pu-O coordination number drops to predominantly 6-fold, compared to 8-fold in the stoichiometric fluorite structure.[4]

Properties

editPlutonium dioxide is a stable ceramic material with an extremely low solubility in water and with a high melting point (2,744 °C). The melting point was revised upwards in 2011 by several hundred degrees, based on evidence from rapid laser melting studies which avoid contamination by any container material.[5]

As with all plutonium compounds, it is subject to control under the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty.

Synthesis

editPlutonium spontaneously oxidizes to PuO2 in an atmosphere of oxygen. Plutonium dioxide is mainly produced by calcination of plutonium(IV) oxalate, Pu(C2O4)2·6H2O, at 300 °C. Plutonium oxalate is obtained during the reprocessing of nuclear fuel as plutonium is dissolved in a solution of nitric and hydrofluoric acid.[6] Plutonium dioxide can also be recovered from molten-salt breeder reactors by adding sodium carbonate to the fuel salt after any remaining uranium is removed from the salt as its hexafluoride.

Applications

editPuO2, along with UO2, is used in MOX fuels for nuclear reactors. Plutonium-238 dioxide is used as fuel for several deep-space spacecraft such as the Cassini, Voyager, Galileo and New Horizons probes as well as in the Curiosity and Perseverance rovers on Mars. The isotope decays by emitting α-particles, which then generate heat (see radioisotope thermoelectric generator). There have been concerns that an accidental re-entry into Earth's atmosphere from orbit might lead to the break-up and/or burn-up of a spacecraft, resulting in the dispersal of the plutonium, either over a large tract of the planetary surface or within the upper atmosphere. However, although at least two spacecraft carrying PuO2 RTGs have reentered the Earth's atmosphere and burned up (Nimbus B-1 in May 1968 and the Apollo 13 Lunar Module in April 1970),[7][8] the RTGs from both spacecraft survived reentry and impact intact, and no environmental contamination was noted in either instance; in fact, the Nimbus RTG was recovered intact from the Pacific Ocean seafloor and launched aboard Nimbus 3 one year later. In any case, RTGs since the mid-1960s have been designed to remain intact in the event of reentry and impact, following the 1964 launch failure of Transit 5-BN-3 (the early-generation plutonium RTG on board disintegrated upon reentry and dispersed radioactive material into the atmosphere north of Madagascar, prompting a redesign of all U.S. RTGs then in use or under development).[9]

Physicist Peter Zimmerman, following up a suggestion by Ted Taylor, demonstrated that a low-yield (1-kiloton) nuclear weapon could be made relatively easily from plutonium dioxide.[10] Such bomb would require a considerably larger critical mass than one made from elemental plutonium (almost three times larger, even with the dioxide at maximum crystal density; if the dioxide were in powder form, as is often encountered, the critical mass would be much higher still), due both to the lower density of plutonium in dioxide compared with elemental plutonium and to the added inert mass of the oxygen contained.[11]

Toxicology

editThe behavior of plutonium dioxide in the body varies with the way in which it is taken. When ingested, most of it will be eliminated from the body quite rapidly in body wastes,[12] but a small part will dissolve into ions in acidic gastric juice and cross the blood barrier, depositing itself in other chemical forms in other organs such as in phagocytic cells of lung, bone marrow and liver.[13]

In particulate form, plutonium dioxide at a particle size less than 10 μm[14] is radiotoxic if inhaled due to its strong alpha-emission.[15]

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ Christine Guéneau; Alain Chartier; Paul Fossati; Laurent Van Brutzel; Philippe Martin (2020). "Thermodynamic and Thermophysical Properties of the Actinide Oxides". Comprehensive Nuclear Materials 2nd Ed. 7: 111–154. doi:10.1016/B978-0-12-803581-8.11786-2. ISBN 9780081028667.

- ^ "Nitric acid processing". Los Alamos Laboratory.

- ^ Greenwood, Norman N.; Earnshaw, Alan (1984). Chemistry of the Elements. Oxford: Pergamon Press. p. 1471. ISBN 978-0-08-022057-4.

- ^ Wilke, Stephen; Benmore, Chris; Alderman, Oliver; Sivaraman, Ganesh; Ruehl, Matthew; Hawthorne, Krista; Tamalonis, Anthony; Andersson, David; Williamson, Mark; Weber, Richard (2024). "Plutonium oxide melt structure and covalency". Nature Materials. 23: 884–889. doi:10.1038/s41563-024-01883-3.

- ^ De Bruycker, F.; Boboridis, K.; Pöml, P.; Eloirdi, R.; Konings, R. J. M.; Manara, D. (2011). "The melting behaviour of plutonium dioxide: A laser-heating study". Journal of Nuclear Materials. 416 (1–2): 166–172. Bibcode:2011JNuM..416..166D. doi:10.1016/j.jnucmat.2010.11.030.

- ^ Jeffrey A. Katalenich Michael R. Hartman Robert C. O’Brien Steven D. Howe (Feb 2013). "Fabrication of Cerium Oxide and Uranium Oxide Microspheres for Space Nuclear Power Applications" (PDF). Proceedings of Nuclear and Emerging Technologies for Space 2013: 2. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-10-07. Retrieved 2016-07-27.

- ^ A. Angelo Jr. and D. Buden (1985). Space Nuclear Power. Krieger Publishing Company. ISBN 0-89464-000-3.

- ^ "General Safety Considerations" (PDF). Fusion Technology Institute, University of Wisconsin–Madison. Spring 2000. Archived from the original (PDF lecture notes) on 2018-09-15. Retrieved 2017-10-20.

- ^ "Transit". Encyclopedia Astronautica. Archived from the original on June 24, 2002. Retrieved 2013-05-07.

- ^ Michael Singer; David Weir & Barbara Newman Canfield (Nov 26, 1979). "Nuclear Nightmare: America's Worst Fear Come True". New York Magazine.

- ^ Sublette, Carey. "4.1 Elements of Fission Weapon Design". The Nuclear Weapon Archive. 4.1.7.1.2.1 Plutonium Oxide. Retrieved 20 October 2017.

The critical mass of reactor grade plutonium is about 13.9 kg (unreflected), or 6.1 kg (10 cm nat. U) at a density of 19.4. A powder compact with a density of 8 would thus have a critical mass that is (19.4/8)^2 time higher: 82 kg (unreflected) and 36 kg (reflected), not counting the weight of the oxygen (which adds another 14%). If compressed to crystal density these values drop to 40 kg and 17.5 kg.

- ^ United States Nuclear Regulatory Commission, Fact sheet on plutonium (accessed Nov 29 2013)

- ^ Gwaltney-Brant, Sharon M. (2013-01-01), Haschek, Wanda M.; Rousseaux, Colin G.; Wallig, Matthew A. (eds.), "Chapter 41 - Heavy Metals", Haschek and Rousseaux's Handbook of Toxicologic Pathology (Third Edition), Boston: Academic Press, pp. 1315–1347, ISBN 978-0-12-415759-0, retrieved 2022-04-10

- ^ World Nuclear Society, Plutonium Archived 2015-08-18 at the Wayback Machine (accessed Nov 29 2013)

- ^ "Toxicological Profile For Plutonium" (PDF). U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. 2007-09-27. Retrieved 2009-04-23.