Tenerife (/ˌtɛnəˈriːf/ TEN-ə-REEF; Spanish: [teneˈɾife] ; formerly spelled Teneriffe) is the largest and most populous island of the Canary Islands.[4] It is home to 42.9% of the total population of the archipelago.[4] With a land area of 2,034.38 square kilometres (785.48 sq mi) and a population of 948,815 inhabitants as of January 2023,[5][6] it is also the most populous island of Spain[4] and of Macaronesia.[7]

Satellite view (April 2023) | |

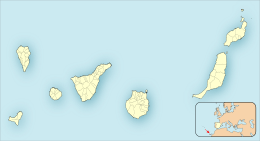

Location of Tenerife in the Canary Islands | |

| Geography | |

|---|---|

| Location | Atlantic Ocean |

| Coordinates | 28°16′7″N 16°36′20″W / 28.26861°N 16.60556°W |

| Archipelago | Canary Islands |

| Area | 2,034.38 km2 (785.48 sq mi)[1] |

| Coastline | 342 km (212.5 mi)[1] |

| Highest elevation | 3,715 m (12188 ft)[2] |

| Highest point | Teide |

| Administration | |

Spain | |

| Autonomous Community | Canary Islands |

| Province | Santa Cruz de Tenerife |

| Capital and largest city | Santa Cruz de Tenerife (pop. 208,906) |

| President of the cabildo insular | Rosa Dávila Mamely (2023) |

| Demographics | |

| Demonym | tinerfeño/a; chicharrero/a |

| Population | 948,815 (start of 2023)[3] |

| Pop. density | 466.39/km2 (1207.94/sq mi) |

| Languages | Spanish, specifically Canarian Spanish, formerly Guanche |

| Ethnic groups | Spanish, other minority groups |

| Additional information | |

| Time zone | |

| • Summer (DST) | |

| Official website | www |

Approximately five million tourists visit Tenerife each year; it is the most visited island in the archipelago.[8] It is one of the most important tourist destinations in Spain[9] and the world,[10] hosting one of the world's largest carnivals, the Carnival of Santa Cruz de Tenerife.

The capital of the island, Santa Cruz de Tenerife, is also the seat of the island council (cabildo insular). That city and Las Palmas de Gran Canaria are the co-capitals of the autonomous community of the Canary Islands. The two cities are both home to governmental institutions, such as the offices of the presidency and the ministries. This has been the arrangement since 1927, when the Crown ordered it. (After the 1833 territorial division of Spain, until 1927, Santa Cruz de Tenerife was the sole capital of the Canary Islands).[11][12] Santa Cruz contains the modern Auditorio de Tenerife, the architectural symbol of the Canary Islands.[13][14]

The island is home to the University of La Laguna. Founded in 1792 in San Cristóbal de La Laguna, it is the oldest university in the Canaries. The city of La Laguna is a UNESCO World Heritage Site. It is the second most populous city on the island, and the third most populous in the archipelago. It was the capital of the Canary Islands before Santa Cruz replaced it in 1833.[15] Tenerife is served by two airports; Tenerife North Airport and Tenerife South Airport.

Teide National Park, located in the center of the island, is also a UNESCO World Heritage Site. It includes Mount Teide, which has the highest elevation in Spain, and the highest elevation among all the islands in the Atlantic Ocean. It is also the third-largest volcano in the world, when measured from its base.[16] Another geographical feature of the island, the Macizo de Anaga (massif), has been designated as a UNESCO Biosphere Reserve since 2015.[17] Tenerife also has the largest number of endemic species in Europe.[17]

Toponymy

editThe name 'Tenerife' likely comes from Tamazight, but there is no consensus on its correct interpretation.[18]

The island's indigenous people, the Guanche Berbers, referred to the island as Achinet or Chenet in their language (variant spellings are found in the literature). According to Pliny the Younger, Berber king Juba II sent an expedition to the Canary Islands and Madeira; he named the Canary Islands for the particularly ferocious dogs (canaria) on the island.[19] Juba II and the ancient Romans called the island of Tenerife Nivaria, from the Latin word nix (nsg.; gsg. nivis, npl. nives), meaning "snow", after the snow-covered peak of the Mount Teide volcano.[20] Later maps dating to the 14th and 15th century, drawn by mapmakers such as Bontier and Le Verrier, called the island Isla del Infierno, ("Hell Island"), due to Mount Teide's volcanic eruptions and other volcanic activity.

Although the name given to the island by the Benahoaritas (the indigenous peoples of La Palma) was derived from the words teni ("mountain") and ife ("white"),[citation needed] after the island was colonized by the Spanish the name was modified by Spanish phonology: the letter "r" was added to link the two words, producing the single word Tenerife.[21][22]

However, throughout history, other explanations for the origin of island's name have been proposed. For example, the 17th-century historians Juan Núñez de la Peña and Tomás Arias Marín de Cubas, among others, suggested that the indigenous peoples might have named the island for the famous Guanche king, Tinerfe, nicknamed "the Great", who ruled Tenerife before the Canary Islands were conquered by Castile.[23]

Demonym

editThe formal demonym used to refer to the people of Tenerife is Tinerfeño/a; also used colloquially is the term chicharrero/a.[24] In modern society, the latter term is generally applied only to inhabitants of the capital, Santa Cruz. The term chicharrero was once a derogatory term used by the people of La Laguna when it was the capital, to refer to the poorer inhabitants and fishermen of Santa Cruz. The fishermen typically caught mackerel and other residents ate potatoes, assumed to be of low quality by the elite of La Laguna.[24] As Santa Cruz grew in commerce and status, it replaced La Laguna as capital of Tenerife in 1833 during the reign of Fernando VII. Then the inhabitants of Santa Cruz used the former insult to identify as residents of the new capital, at La Laguna's expense.[24]

History

editThe earliest known human settlement in the islands, dating to around 200 BCE, was established by Berbers known as the Guanches.[25] However, the Cave of the Guanches in the northern municipality of Icod de los Vinos has provided the oldest chronologies of the Canary Islands, with dates around the sixth century BCE.[26]

In terms of technology, the Guanches can be placed among the peoples of the Stone Age, although scholars often reject this classification because of its ambiguity. Guanche culture was more advanced culturally, possibly because of Berber cultural features imported from North Africa, but less technologically advanced due to the scarcity of raw materials, especially minerals that would have allowed for the extraction and working of metals. The main activity was gathering food from nature; though fishing and shellfish collection were supplemented with some agricultural practices.[27]

As for religion and cosmology, the Guanches were polytheistic, with further widespread belief in an astral cult. They also had an animistic religiosity that sacralized certain places, mainly rocks and mountains. Although the Guanches worshiped many gods and ancestral spirits, among the most important were Achamán (the god of the sky and supreme creator), Chaxiraxi (the mother goddess, identified later with the Virgin of Candelaria), Magec (the god of the sun), and Guayota (the demon who is the main cause of evil). Especially significant was the cult of the dead, which practiced the mummification of corpses. In addition, small anthropomorphic and zoomorphic stone and clay figurines of the kind typically associated with rituals have been found on the island. Scholars believe they were used as idols, the most prominent of which is the so-called Idol of Guatimac, which is thought to represent a genius or protective spirit.

Territorial organisation before the conquest (The Guanches)

editThe title of mencey was given to the monarch or king of the Guanches of Tenerife, who governed a menceyato or kingdom. This role was later referred to as a "captainship" by the conquerors. Tinerfe "the Great", son of the mencey Sunta, governed the island from Adeje in the south. However, upon his death, his nine children rebelled and argued bitterly about how to divide the island.

Two independent achimenceyatos were created on the island, and the island was divided into nine menceyatos. The menceyes within them formed what would be similar to municipalities today.[28] The menceyatos and their menceyes (ordered by the names of descendants of Tinerfe who ruled them) were the following:

- Taoro. Menceyes: Bentinerfe, Inmobach, Bencomo and Bentor. Today it includes Puerto de la Cruz, La Orotava, La Victoria de Acentejo, La Matanza de Acentejo, Los Realejos and Santa Úrsula.

- Güímar. Menceyes: Acaymo, Añaterve y Guetón. Today this territory is made up of El Rosario, Candelaria, Arafo and Güímar

- Abona. Menceyes: Atguaxoña and Adxoña (Adjona). Today it includes Fasnia, Arico, Granadilla de Abona, San Miguel de Abona and Arona.

- Anaga. Menceyes: Beneharo and Beneharo II. Today this territory spans the municipalities of Santa Cruz de Tenerife and San Cristóbal de La Laguna.

- Tegueste. Menceyes: Tegueste, Tegueste II y Teguaco. Today this territory is made up of Tegueste, part of the coastal zone of La Laguna.

- Tacoronte: Menceyes: Rumén and Acaymo. Today this territory is made up of Tacoronte and El Sauzal

- Icode. Menceyes: Chincanayro and Pelicar. Today this territory is made up of San Juan de la Rambla, La Guancha, Garachico and Icod de los Vinos.

- Daute. Menceyes: Cocanaymo and Romen. Today this territory is occupied by El Tanque, Los Silos, Buenavista del Norte and Santiago del Teide.

- Adeje. Menceyes. Atbitocazpe, Pelinor, and Ichasagua. It included what today are the municipalities of Guía de Isora, Adeje and Vilaflor

The achimenceyato of Punta del Hidalgo was governed by Aguahuco, a "poor noble" who was an illegitimate son of Tinerfe and Zebenzui.

Spanish conquest

editTenerife was the last island of the Canaries to be conquered and the one that took the longest time to submit to the Castilian troops. Although the traditional dates of the conquest of Tenerife are established between 1494 (landing of Alonso Fernández de Lugo) and 1496 (the complete conquest of the island), attempts to annex the island of Tenerife to the Crown of Castile date back at least to 1464.[29]

In 1464, Diego Garcia de Herrera, Lord of the Canary Islands, took symbolic possession of the island in the Barranco del Bufadero (Ravine of the Bufadero),[30] signing a peace treaty with the Guanche chiefs (menceyes) which allowed the mencey Anaga to build a fortified tower on Guanche land, where the Guanches and the Spanish held periodic treaty talks until the Guanches demolished it around 1472.[31]

In 1492 the governor of Gran Canaria Francisco Maldonado organized a raid that ended in disaster for the Spaniards when they were defeated by Anaga's warriors. In December 1493, the Catholic monarchs, Queen Isabella I of Castile and King Ferdinand II of Aragon, granted Alonso Fernández de Lugo the right to conquer Tenerife. Coming from Gran Canaria in April 1494, the conqueror landed on the coast of present-day Santa Cruz de Tenerife in May, and disembarked with about 2,000 men on foot and 200 on horseback.[32] After taking the fort, the army prepared to move inland, later capturing the native kings of Tenerife and presenting them to Isabella and Ferdinand.

The menceyes of Tenerife had differing responses to the conquest. They divided into the side of peace (Spanish: bando de paz) and the side of war (Spanish: bando de guerra). The first included the menceyatos of Anaga, Güímar, Abona and Adeje. The second group consisted of the people of Tegueste, Tacoronte, Taoro, Icoden and Daute. Those opposed to the conquest fought the invaders tenaciously, resisting their rule for two years. Castillian forces under the Adelantado ("military governor") de Lugo suffered a crushing defeat at the hands of the Guanches in the First Battle of Acentejo on 31 May 1494, but defeated them at the Second Battle of Acentejo on 25 December 1494. The Guanches were eventually overcome by superior technology and the arms of the invaders, and surrendered to the Crown of Castile in 1496.[33]

Spanish rule

editMany of the natives died from new infectious diseases, such as influenza and probably smallpox, to which they lacked resistance or acquired immunity. The new colonists intermarried with the local native population. For a century after the conquest, many new colonists settled on the island, including immigrants from the diverse territories of the growing Spanish Empire, such as Flanders, Italy, and Germany.

As the population grew, it cleared Tenerife's pine forests for fuel and to make fields for agriculture for crops both for local consumption and for export. Sugar cane was introduced in the 1520s as a commodity crop on major plantations; it was a labor-intensive crop in all phases of cultivation and processing. In the following centuries, planters cultivated wine grapes, cochineal for making dyes, and plantains for use and export.[34]

Trade with the Americas

editIn the commerce of the Canary Islands with the Americas of the 18th century, Tenerife was the hegemonic island, since it exceeded 50% of the number of ships and 60% of the tonnage. In the islands of La Palma and Gran Canaria, the percentage was around 19% for the first and 7% for the second.[35] The volume of traffic between the Indies and the Canary Islands was unknown, but was very important and concentrated almost exclusively in Tenerife.[35]

Among the products that are exported were cochineal, rum and sugar cane, which were landed mainly in the ports of the Americas such as La Guaira, Havana, Campeche and Veracruz. Many sailors from Tenerife joined this transcontinental maritime trade, among which the corsair Amaro Rodríguez Felipe, more commonly known as Amaro Pargo, Juan Pedro Dujardín and Bernardo de Espinosa, both companions of Amaro Pargo, among others.[36]

Emigration to the Americas

editTenerife, like the other islands, has maintained a close relationship with Latin America, as both were part of the Spanish Empire. From the start of the colonization of the New World, many Spanish expeditions stopped at the island for supplies on their way to the Americas. They also recruited many tinerfeños for their crews, who formed an integral part of the conquest expeditions. Others joined ships in search of better prospects. It is also important to note the exchange in plant and animal species that made those voyages.[37]

After a century and a half of relative growth, based on the grape growing sector, numerous families emigrated, especially to Venezuela and Cuba. The Crown wanted to encourage population of underdeveloped zones in the Americas to pre-empt the occupation by foreign forces, as had happened with the English in Jamaica and the French in the Guianas and western Hispaniola (which the French renamed as Saint-Domingue). Canary Islanders, including many tinerfeños, left for the New World.

The success in cultivation of new crops of the Americas, such as cocoa in Venezuela and tobacco in Cuba, contributed to the population exodus from towns such as Buenavista del Norte, Vilaflor, or El Sauzal in the late 17th century. The village of San Carlos de Tenerife was founded in 1684 by Canary Islanders on Santo Domingo. The people from Tenerife were recruited for settlement to build up the town from encroachment by French colonists established in the western side of Hispaniola. Between 1720 and 1730, the Crown moved 176 families, including many tinerfeños, to the Caribbean island of Puerto Rico. In 1726, about 25 island families migrated to the Americas to collaborate on the foundation of Montevideo. Four years later, in 1730, another group left that founded San Antonio the following year in what became Texas. Between 1777 and 1783, more islanders emigrated from Santa Cruz de Tenerife to settle in what became St. Bernard Parish, Louisiana, during the period when Spain ruled this former French territory west of the Mississippi River. Some groups went to Western or Spanish Florida.[37]

Tenerife saw the arrival of the First Fleet to Botany Bay in June 1787, which consisted of 11 ships that departed from Portsmouth, England, on 13 May 1787 to found the penal colony that became the first European settlement in Australia. The Fleet consisted of two Royal Navy vessels, three store ships and six convict ships carrying between 1,000 and 1,500 convicts, marines, seamen, civil officers and free people (accounts differ on the numbers), and a vast quantity of stores. On 3 June 1787, the fleet anchored at Santa Cruz at Tenerife. Here, fresh water, vegetables and meat were brought on board. Commander of the fleet, Capt. Arthur Phillip and the chief officers were entertained by the local governor, while one convict tried unsuccessfully to escape. On 10 June they set sail to cross the Atlantic to Rio de Janeiro, taking advantage of favourable trade winds and ocean currents.

In June 1799, the Prussian-born naturalist Alexander von Humboldt spent five full days on Tenerife on the first leg of his soon world-famous American journey (1799–1804) and climbed the Pico del Teide.[38]

Emigration to the Americas (mainly Cuba and Venezuela) continued during the 19th and early 20th century, due to the lack of economic opportunity and the relative isolation of the Canary Islands. Since the late 20th century, island protectionist economic laws and a strong development in the tourism industry have strengthened the economy and attracted new migrants. Tenerife has received numerous new residents, including the "return" of many descendants of some islanders who had departed five centuries before.[37]

Military history

editThe most notable conflict was the British invasion of Tenerife in 1797.[39] On 25 July 1797, Admiral Horatio Nelson launched an attack at Santa Cruz de Tenerife, now the capital of the island. After a ferocious fight which resulted in many casualties, General Antonio Gutiérrez de Otero y Santayana organized a defense to repel the invaders. Whilst leading a landing party, Nelson was seriously wounded in his right arm by grapeshot or a musket ball, necessitating amputation of most of the arm.[40] Legend tells that he was wounded by the Spanish cannon Tiger (Spanish: Tigre) as he was trying to disembark on the Paso Alto coast.[34]

On 5 September 1797, the British attempted another attack in the Puerto Santiago region, which was repelled by the inhabitants of Santiago del Teide. Some threw rocks at the British from the heights of the cliffs of Los Gigantes.

The island was also attacked by British commanders Robert Blake, Walter Raleigh, John Hawkins and Woodes Rogers.[41]

Modern history

editFrom 1833 to 1927, Santa Cruz de Tenerife was the sole capital of the Canary Islands. In 1927, the government ordered that the capital be shared with Las Palmas, as it remains at present.[11][12] This change in status has encouraged development in Las Palmas.

Tourists began visiting Tenerife from Spain, the United Kingdom, and northern Europe in large numbers in the 1890s. They especially were attracted to the destinations of the northern towns of Puerto de la Cruz and Santa Cruz de Tenerife.[42] Independent shipping business, such as the Yeoward Brothers Shipping Line, helped boost the tourist industry during this time, adding to ships that carried passengers.[43] The naturalist Alexander von Humboldt ascended the peak of Mount Teide and remarked on the beauty of the island.

Before his rise to power, Francisco Franco was posted to Tenerife in March 1936 by a Republican government wary of his influence and political leanings. However, Franco received information and in Gran Canaria agreed to collaborate in the military coup that would result in the Spanish Civil War; the Canaries fell to the Nationalists in July 1936. In the 1950s, the misery of the post-war years caused thousands of the island's inhabitants to emigrate to Cuba and other parts of Latin America.

Tenerife was the site of the deadliest accident ever in commercial aviation. The Tenerife airport disaster occurred on 27 March 1977 when two Boeing 747s, KLM Flight 4805 and Pan Am Flight 1736 collided on the runway at Los Rodeos Airport in heavy fog conditions, causing the deaths of 583 passengers and crew. A few years later, Dan Air Flight 1008 crashed into a mountain while on approach to Tenerife North, killing 146 people. The plane was travelling too close to an Iberia Air turboprop plane and was asked to go into a holding pattern.[44]

At the beginning of the 21st century, the so-called Riada de Tenerife of 2002 took place on 31 March of that year. It was a phenomenon of cold drop characterized by the repeated fall of torrential rains accompanied by thunder and lightning, affecting the metropolitan area of Santa Cruz de Tenerife and extending in the NE direction towards the San Andrés area.[45] The rains caused 8 dead, 12 missing and dozens of injured.[46] In addition to the human losses, the flood caused considerable material damage, 70,000 people without light as well as the total or partial destruction of at least 400 homes. The losses were calculated at 90 million euros.[47]

In November 2005, Tenerife was the Canary Island most affected by Tropical Storm Delta. Winds of 140 km/h were recorded on the coast and almost 250 km/h on the Teide, Tenerife's summit.

Geography

editThe oldest mountain ranges in Tenerife rose from the Atlantic Ocean by volcanic eruption which gave birth to the island around twelve million years ago.[48] The island as it is today was formed three million years ago by the fusion of three islands made up of the mountain ranges of Anaga, Teno and Valle de San Lorenzo,[48] due to volcanic activity from Teide. The volcano is visible from most parts of the island today, and the crater is 17 kilometres (11 miles) long at some points. Tenerife is the largest island of the Canary Islands and the Macaronesia region.[7]

Climate

editTenerife is characterized by a generally dry, warm climate. The island has 2 main different climatic areas (as by Köppen climate classification) yet it actually has 5 different climatic areas.[49]

Global climate change has had a major impact on the island, with diminishing rainfall and hot, dry winds affecting vegetation and contributing to an increasing propensity to being subject to forest fires. On August 15, 2023, a forest fire determined to be caused by arson necessitated the evacuation of 12,000 residents within a week.[50]

The main climates are the hot semi-arid/arid climate (Köppen: BSh and BWh) and the subtropical Mediterranean Climate (Köppen: Csb and Csa) inland or at higher altitudes. The low altitude/coastal areas of the island have average temperatures of 18–20 °C (64–68 °F) in the winter months and 24–26 °C (75–79 °F) in the summer months. There is a high annual total of days of sunshine and low precipitation in the coastal areas. The inland/high altitude areas, such as La Laguna, receive much more precipitation and are generally cloudier, as well as the temperatures have a considerable difference, with an average of 13–14 °C (55–57 °F) in the winter and 20–21 °C (68–70 °F) in the summer. The moderate climate of Tenerife is controlled to a great extent by the trade winds, whose humidity is condensed principally over the north and northeast of the island, creating cloud banks that range between 600 and 1,800 metres (2,000 and 5,900 feet) in height. The cold sea currents of the Canary Islands also have a cooling effect on the coasts and its beaches, while the topography of the landscape plays a role in climatic differences on the island with its many valleys. The moderating effect of the marine air makes extreme heat a rare occurrence and frost an impossibility at sea level. The lowest recorded temperature in central Santa Cruz is 8.1 °C (46.6 °F), the coldest month on record still had a relatively mild average temperature of 15.8 °C (60.4 °F).[51] Summer temperatures are highest in August, with an average high of 29 °C (84 °F) in Santa Cruz, similar to those of places as far north as Barcelona and Majorca, because of the greater maritime influence. At a higher elevation in San Cristóbal de La Laguna, the climate transitions to a Mediterranean climate with higher precipitation amounts and lower temperatures year round. The climate of Santa Cruz is very typical of the Canaries, albeit only slightly warmer than the climate of Las Palmas.

Major climatic contrasts on the island are evident, especially during the winter months when it is possible to enjoy the warm sunshine on the coast and experience snow within kilometres, 3,000 metres (10,000 feet) above sea level on El Teide.[52] There are also major contrasts at low altitude, where the climate ranges from arid (Köppen BWh) on the southeastern side represented by Santa Cruz de Tenerife to Mediterranean (Csa/Csb) on the northwestern side in Buena Vista del Norte and La Orotava.[53]

The center of the island is characterized by forests because of the much higher precipitation, mostly Canary Island pine forests in the Teide National Park at altitudes from 1,300 to 2,100 metres (4,300 to 6,900 ft).[54] Subtropical cloud forests characterised by laurisilva[55] are commonly found in the Anaga National Park and Monte de Agua in the Teno Rural Park, with altitudes from 600 to 1,000 metres (2,000 to 3,300 ft) and annual averages from 15 to 19 °C (59 to 66 °F) and 600 to 1,200 metres (2,000 to 3,900 ft) in the latter.[56]

The north and south of Tenerife similarly have different climatic characteristics because of the rain shadow effect. The windward northwestern side of the island receives 73 percent of all precipitation on the island, and the relative humidity of the air is superior and the insolation inferior. The pluviometric maximums are registered on the windward side at an average altitude of between 1,000 and 1,200 metres (3,300 and 3,900 feet), almost exclusively in the La Orotava mountain range.[52] Although climatic differences in rainfall and sunshine on the island exist, overall annual precipitation is low and the summer months from May to September are normally completely dry. Rainfall, similar to that of Southern California, can also be extremely erratic from one year to another.[57]

| Climate data for Santa Cruz de Tenerife (1981–2010), Extremes (1920–present) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 28.4 (83.1) |

31.2 (88.2) |

35.4 (95.7) |

35.2 (95.4) |

36.4 (97.5) |

37.1 (98.8) |

42.6 (108.7) |

40.4 (104.7) |

39.3 (102.7) |

38.1 (100.6) |

34.0 (93.2) |

28.2 (82.8) |

42.6 (108.7) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 21.0 (69.8) |

21.2 (70.2) |

22.1 (71.8) |

22.7 (72.9) |

24.1 (75.4) |

26.2 (79.2) |

28.7 (83.7) |

29.0 (84.2) |

28.1 (82.6) |

26.3 (79.3) |

24.1 (75.4) |

22.1 (71.8) |

24.6 (76.3) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 18.2 (64.8) |

18.3 (64.9) |

19.0 (66.2) |

19.7 (67.5) |

21.0 (69.8) |

22.9 (73.2) |

25.0 (77.0) |

25.5 (77.9) |

24.9 (76.8) |

23.4 (74.1) |

21.3 (70.3) |

19.4 (66.9) |

21.5 (70.7) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 15.4 (59.7) |

15.3 (59.5) |

15.9 (60.6) |

16.5 (61.7) |

17.8 (64.0) |

19.5 (67.1) |

21.2 (70.2) |

21.9 (71.4) |

21.7 (71.1) |

20.3 (68.5) |

18.4 (65.1) |

16.6 (61.9) |

18.4 (65.1) |

| Record low °C (°F) | 9.4 (48.9) |

8.1 (46.6) |

9.5 (49.1) |

9.4 (48.9) |

12.0 (53.6) |

13.4 (56.1) |

16.5 (61.7) |

14.6 (58.3) |

16.5 (61.7) |

14.6 (58.3) |

10.1 (50.2) |

10.0 (50.0) |

8.1 (46.6) |

| Average rainfall mm (inches) | 31.5 (1.24) |

35.4 (1.39) |

37.8 (1.49) |

11.6 (0.46) |

3.6 (0.14) |

0.9 (0.04) |

0.1 (0.00) |

2.0 (0.08) |

6.8 (0.27) |

18.7 (0.74) |

34.1 (1.34) |

43.2 (1.70) |

225.7 (8.89) |

| Average rainy days (≥ 1.0 mm) | 8.0 | 7.2 | 6.9 | 5.5 | 2.9 | 0.9 | 0.2 | 0.8 | 2.7 | 6.1 | 8.8 | 9.4 | 59.4 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 64 | 65 | 62 | 61 | 61 | 61 | 58 | 60 | 64 | 66 | 65 | 66 | 63 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 178 | 186 | 221 | 237 | 282 | 306 | 337 | 319 | 253 | 222 | 178 | 168 | 2,887 |

| Source 1: Agencia Estatal de Meteorología[58] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: Agencia Estatal de Meteorología[59] | |||||||||||||

| Climate data for Tenerife South Airport (1981–2010), Extremes (1980–present) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 29.3 (84.7) |

30.0 (86.0) |

34.0 (93.2) |

35.6 (96.1) |

37.7 (99.9) |

36.2 (97.2) |

42.9 (109.2) |

44.3 (111.7) |

41.8 (107.2) |

37.0 (98.6) |

35.2 (95.4) |

30.0 (86.0) |

44.3 (111.7) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 21.7 (71.1) |

22.0 (71.6) |

23.1 (73.6) |

23.1 (73.6) |

23.9 (75.0) |

25.4 (77.7) |

27.7 (81.9) |

28.4 (83.1) |

27.9 (82.2) |

26.8 (80.2) |

24.8 (76.6) |

22.8 (73.0) |

24.8 (76.6) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 18.4 (65.1) |

18.5 (65.3) |

19.3 (66.7) |

19.5 (67.1) |

20.4 (68.7) |

22.1 (71.8) |

24.0 (75.2) |

24.7 (76.5) |

24.5 (76.1) |

23.4 (74.1) |

21.5 (70.7) |

19.7 (67.5) |

21.4 (70.5) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 15.2 (59.4) |

15.0 (59.0) |

15.6 (60.1) |

16.0 (60.8) |

17.0 (62.6) |

18.8 (65.8) |

20.2 (68.4) |

21.1 (70.0) |

21.1 (70.0) |

20.0 (68.0) |

18.2 (64.8) |

16.5 (61.7) |

17.9 (64.2) |

| Record low °C (°F) | 9.0 (48.2) |

9.8 (49.6) |

9.6 (49.3) |

12.2 (54.0) |

13.0 (55.4) |

14.6 (58.3) |

16.8 (62.2) |

17.1 (62.8) |

16.6 (61.9) |

14.8 (58.6) |

12.0 (53.6) |

10.4 (50.7) |

9.0 (48.2) |

| Average rainfall mm (inches) | 16.6 (0.65) |

19.9 (0.78) |

14.7 (0.58) |

7.4 (0.29) |

1.1 (0.04) |

0.1 (0.00) |

0.1 (0.00) |

1.3 (0.05) |

3.6 (0.14) |

11.9 (0.47) |

26.3 (1.04) |

30.3 (1.19) |

133.3 (5.23) |

| Average rainy days (≥ 1.0 mm) | 1.8 | 2.2 | 1.9 | 1.1 | 0.3 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.2 | 0.6 | 1.6 | 1.9 | 3.5 | 15.1 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 62 | 64 | 63 | 65 | 66 | 68 | 65 | 67 | 68 | 67 | 64 | 66 | 65 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 193 | 195 | 226 | 219 | 246 | 259 | 295 | 277 | 213 | 214 | 193 | 195 | 2,725 |

| Source 1: Agencia Estatal de Meteorología[60] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: Agencia Estatal de Meteorología[61] | |||||||||||||

| Climate data for San Cristóbal de La Laguna – Tenerife North Airport (altitude: 632 metres (2,073 feet)) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 25.6 (78.1) |

26.9 (80.4) |

33.2 (91.8) |

33.0 (91.4) |

37.6 (99.7) |

37.9 (100.2) |

41.4 (106.5) |

41.2 (106.2) |

38.0 (100.4) |

33.2 (91.8) |

31.0 (87.8) |

25.2 (77.4) |

41.4 (106.5) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 16.0 (60.8) |

16.7 (62.1) |

18.2 (64.8) |

18.5 (65.3) |

20.1 (68.2) |

22.2 (72.0) |

24.7 (76.5) |

25.7 (78.3) |

24.9 (76.8) |

22.5 (72.5) |

19.7 (67.5) |

17.1 (62.8) |

20.5 (68.9) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 13.1 (55.6) |

13.4 (56.1) |

14.5 (58.1) |

14.7 (58.5) |

16.1 (61.0) |

18.1 (64.6) |

20.2 (68.4) |

21.2 (70.2) |

20.7 (69.3) |

18.9 (66.0) |

16.5 (61.7) |

14.3 (57.7) |

16.8 (62.2) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 10.2 (50.4) |

10.0 (50.0) |

10.7 (51.3) |

10.9 (51.6) |

12.0 (53.6) |

14.0 (57.2) |

15.7 (60.3) |

16.6 (61.9) |

16.5 (61.7) |

15.2 (59.4) |

13.3 (55.9) |

11.5 (52.7) |

13.0 (55.4) |

| Record low °C (°F) | 3.2 (37.8) |

3.4 (38.1) |

2.0 (35.6) |

4.2 (39.6) |

6.0 (42.8) |

8.5 (47.3) |

8.5 (47.3) |

7.0 (44.6) |

9.2 (48.6) |

6.8 (44.2) |

6.2 (43.2) |

3.5 (38.3) |

2.0 (35.6) |

| Average rainfall mm (inches) | 80 (3.1) |

70 (2.8) |

61 (2.4) |

39 (1.5) |

19 (0.7) |

11 (0.4) |

6 (0.2) |

5 (0.2) |

16 (0.6) |

47 (1.9) |

81 (3.2) |

82 (3.2) |

517 (20.2) |

| Average rainy days (≥ 1.0 mm) | 11 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 7 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 5 | 10 | 10 | 12 | 95 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 76 | 75 | 71 | 74 | 72 | 73 | 69 | 69 | 71 | 74 | 75 | 79 | 73 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 150 | 168 | 188 | 203 | 234 | 237 | 262 | 269 | 213 | 194 | 155 | 137 | 2,410 |

| Source 1: Agencia Estatal de Meteorología[62] (1981–2010) | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: Agencia Estatal de Meteorología[63] | |||||||||||||

| Climate data for Izaña Teide Observatory (altitude: 2,371 metres (7,779 feet)) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 7.5 (45.5) |

8.0 (46.4) |

10.2 (50.4) |

11.8 (53.2) |

14.5 (58.1) |

18.9 (66.0) |

23.0 (73.4) |

22.6 (72.7) |

18.6 (65.5) |

14.3 (57.7) |

11.1 (52.0) |

8.8 (47.8) |

14.1 (57.4) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 4.3 (39.7) |

4.7 (40.5) |

6.4 (43.5) |

7.6 (45.7) |

10.1 (50.2) |

14.4 (57.9) |

18.5 (65.3) |

18.2 (64.8) |

14.5 (58.1) |

10.6 (51.1) |

7.8 (46.0) |

5.6 (42.1) |

10.2 (50.4) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 1.1 (34.0) |

1.3 (34.3) |

2.7 (36.9) |

3.5 (38.3) |

5.8 (42.4) |

9.9 (49.8) |

14.0 (57.2) |

13.8 (56.8) |

10.4 (50.7) |

6.9 (44.4) |

4.5 (40.1) |

2.4 (36.3) |

6.4 (43.4) |

| Average rainfall mm (inches) | 47 (1.9) |

67 (2.6) |

58 (2.3) |

18 (0.7) |

7 (0.3) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

5 (0.2) |

13 (0.5) |

37 (1.5) |

54 (2.1) |

60 (2.4) |

366 (14.5) |

| Average rainy days (≥ 1.0 mm) | 4.5 | 4.0 | 4.1 | 2.7 | 1.1 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.5 | 1.6 | 3.7 | 4.4 | 5.6 | 32.5 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 50 | 54 | 48 | 45 | 40 | 32 | 25 | 30 | 43 | 55 | 54 | 52 | 44 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 226 | 223 | 260 | 294 | 356 | 382 | 382 | 358 | 295 | 259 | 220 | 218 | 3,473 |

| Source: Agencia Estatal de Meteorología[64] (1981–2010) | |||||||||||||

| Climate data for Vilaflor (altitude: 1,378 metres (4,521 feet) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 13.5 (56.3) |

14.4 (57.9) |

16.0 (60.8) |

16.1 (61.0) |

18.3 (64.9) |

21.2 (70.2) |

27.4 (81.3) |

27.9 (82.2) |

23.5 (74.3) |

18.7 (65.7) |

16.0 (60.8) |

14.5 (58.1) |

19.0 (66.2) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 9.4 (48.9) |

10.2 (50.4) |

11.7 (53.1) |

11.9 (53.4) |

13.8 (56.8) |

16.7 (62.1) |

22.7 (72.9) |

23.0 (73.4) |

19.2 (66.6) |

14.4 (57.9) |

11.4 (52.5) |

10.0 (50.0) |

14.7 (58.5) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 5.4 (41.7) |

6.0 (42.8) |

7.3 (45.1) |

7.2 (45.0) |

9.5 (49.1) |

12.2 (54.0) |

18.0 (64.4) |

18.5 (65.3) |

14.8 (58.6) |

10.4 (50.7) |

8.2 (46.8) |

7.0 (44.6) |

10.2 (50.4) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 49.4 (1.94) |

51.2 (2.02) |

34.1 (1.34) |

24.4 (0.96) |

2.7 (0.11) |

0.4 (0.02) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.8 (0.03) |

7.5 (0.30) |

33.8 (1.33) |

70.6 (2.78) |

56.2 (2.21) |

366.1 (14.41) |

| Source: Gobierno de Canarias[65] (Temperatures:1983–1995; Precipitation:1945–1997) | |||||||||||||

| Buenavista del Norte | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Climate chart (explanation) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Water

editThe volcanic ground of Tenerife, which is of a porous and permeable character, is generally the reason why the soil is able to maximise the absorption of water on an island of low rainfall, with condensation in forested areas and frost deposition on the summit of the island also contributory causes.[67]

Given the irregularity of precipitation and geological conditions on the island, dam construction has been avoided, so most of the water (90 percent) comes from wells and from water galleries (horizontal tunnels bored into the volcano) of which there are thousands on the island, important systems that serve to extract its hydrological resources.[68] These tunnels are very hazardous, with pockets of volcanic gas or carbon dioxide, causing rapid death.[69]

Pollution and air quality

editThe Canary Islands have low levels of air pollution thanks to the lack of factories and industry and the trade winds which naturally move away contaminated air from the islands. According to official data offered by the Health and Industry Ministry in Spain, Tenerife is one of the cleanest places in the country with an air pollution index below the national average.[70] Despite this, there are still agents which affect pollution levels in the island, the main polluting agents being the refinery at Santa Cruz, the thermal power plants at Las Caletillas and Granadilla, and road traffic, increased by the high level of tourism in the island. In addition on the island of Tenerife like on La Palma light pollution must be also controlled, to help the astrophysical observatories located in the island's summits.[71] Water is generally of a very high quality, and all the beaches of the island of Tenerife have been catalogued by the Ministry of Health and Consumption as waters suitable for bathing.[72]

Geology

editTenerife is a rugged volcanic island, sculpted by successive eruptions throughout its history. There are four historically recorded volcanic eruptions, none of which has led to casualties. The first occurred in 1704, when the Arafo, Fasnia and Siete Fuentes volcanoes erupted simultaneously. Two years later, in 1706, the greatest eruption occurred at Trevejo. This volcano produced great quantities of lava which buried the city and port of Garachico. The last eruption of the 18th century happened in 1798 at Cañadas de Teide, in Chahorra. The most recent eruption-in 1909-formed the Chinyero cinder cone in the municipality of Santiago del Teide.[73]

The island is located between 28° and 29° N and the 16° and 17° W meridian. It is situated north of the Tropic of Cancer, occupying a central position between the other Canary Islands of Gran Canaria, La Gomera and La Palma. The island is about 300 km (186 mi) from the African coast, and approximately 1,000 km (621 mi) from the Iberian Peninsula.[74] Tenerife is the largest island of the Canary Islands archipelago, with a surface area of 2,034.38 km2 (785 sq mi)[75] and has the longest coastline, amounting to 342 km (213 mi).[76]

In addition, the highest point, Mount Teide, with an elevation of 3,715 m (12,188 ft) above sea level is the highest point in all of Spain,[77] is also the third largest volcano in the world from its base in the bottom of the sea. For this reason, Tenerife is the 10th-highest island worldwide. It comprises about 200 small barren islets or large rocks including Roques de Anaga, Roque de Garachico, and Fasnia adding a further 213,835 m2 (2,301,701 sq ft) to the total area.[75]

Origins and geological formation

editTenerife is a volcanic island that has built up from the ocean floor during the last 20 million years.[78][79]

Underwater fissural eruptions produced pillow lava, which are produced by the rapid cooling of the magma when it comes in contact with water, obtaining their peculiar shape. This pillow-lava accumulated, constructing the base of the island underneath the sea. As this accumulation approached the surface of the water, gases erupted from the magma due to the reduction of the surrounding pressure. The volcanic eruptions became more violent and had a more explosive character, and resulted in the forming of peculiar geological fragments.[78]

After long-term accumulation of these fragments, the birth of the island occurred at the end of the Miocene epoch. The zones on Tenerife known as Macizo de Teno, Macizo de Anaga and Macizo de Adeje were formed seven million years ago; these formations are called the Ancient Basaltic Series or Series I. These zones were actually three separate islands lying in what is now the extreme west, east, and south of Tenerife.[80]

A second volcanic cycle called the Post-Miocene Formations or Latest Series II, III, IV began three million years ago. This was a much more intense volcanic cycle, which united the Macizo de Teno, Macizo de Anaga and Macizo de Adeje into one island. This new structure, called the Pre-Cañadas Structure (Edificio pre-Cañadas), would be the foundation for what is called the Cañadas Structure I. The Cañadas Structure I experienced various collapses and emitted explosive material that produced the area known as Bandas del sur (in the present-day south-southeast of Tenerife).[78]

Subsequently, upon the ruins of Cañadas Structure I emerged Cañadas Structure II, which was 2,500 metres (8,200 ft) above sea level and emerged with intense explosive activity. About one million years ago, the Dorsal Range (Cordillera Dorsal) emerged by means of fissural volcanic activity occurring amidst the remains of the older Ancient Basaltic Series (Series I). This Dorsal Range emerged as the highest and the longest volcanic structure in the Canary Islands; it was 1,600 metres (5,200 ft) high and 25 kilometres (16 mi) long.[78]

About 800,000 years ago, two gravitational landslides occurred, giving rise to the present-day valleys of La Orotava and Güímar.[78] Finally, around 200,000 years ago, the giant Icod landslide occurred followed by eruptions that raised the Pico Viejo-Teide[81] in the centre of the island, over the Las Cañadas caldera.[78]

Orography and landscape

editThe uneven and steep orography of the island and its variety of climates has resulted in a diversity of landscapes and geographical and geological formations, from the Teide National Park with its extensive pine forests, juxtaposed against the volcanic landscape at the summit of Teide and Malpaís de Güímar, to the Acantilados de Los Gigantes (Cliffs of the Giants) with its vertical precipices. Semidesert areas exist in the south with drought-resistant plants. Other areas range from those protected and enclosed in mountains such as Montaña Roja and Montaña Pelada, the valleys and forests with subtropical vegetation and climate, to those with deep gorges and precipices such as at Anaga and Teno.

Central heights

editThe principal structures in Tenerife, make the central highlands, with the Teide–Pico Viejo complex and the Las Cañadas areas as most prominent. It comprises a semi-caldera of about 130 km2 (50 sq mi) in area, originated by several geological processes explained under the Origin and formation section. The area is partially occupied by the Teide-Pico Viejo strato-volcano and completed by the materials emitted in the different eruptions that took place. A known formation called Los Azulejos, composed by green-tinted rocks were created by hydrothermal processes.[34][78][52]

South of La Caldera is Guajara Mountain, which has an elevation of 2,718 metres (8,917 feet), rising above Teide National Park. At the bottom, is an endorheic basin flanked with very fine sedimentary material which has been deposited from its volcanic processes, and is known as Llano de Ucanca.[34][78][52]

The peak of Teide, at 3,715 metres (12,188 feet) above sea level and more than 7,500 metres (24,606 feet) above the ocean floor, is the highest point of the island, Spanish territory and in the Atlantic Ocean. The volcano is the third largest on the planet, and its central location,[clarification needed] substantial size, looming silhouette in the distance and its snowy landscape in winter give it a unique nature.[82] The original settlers considered Teide a god and Teide was a place of worship.

In 1954, the whole area around it was declared a national park, with further expansion later on. In addition, in June 2007 it was recognised by UNESCO as a World Heritage site.[83] To the west lies the volcano Pico Viejo (Old Peak). On one side of it, is the volcano Chahorra o Narices del Teide, where the last eruption occurred in the vicinity of Mount Teide in 1798.

The Teide is one of the 16 Decade Volcanoes identified by the International Association of Volcanology and Chemistry of the Earth's Interior (IAVCEI) as being worthy of particular study in light of their history of large, destructive eruptions and proximity to populated areas.

Tallest mountains on Tenerife:

| Peak | Elevation (meters) | Elevation (feet) |

|---|---|---|

| Mount Teide | 3,715 | 12,198 |

| Pico Viejo | 3,135 | 10,285 |

| Montaña Blanca | 2,748 | 9,016 |

| Guajara | 2,718 | 8,917 |

Massifs

editThe Anaga massif (Macizo de Anaga), at the northeastern end of the island, has an irregular and rugged topographical profile where, despite its generally modest elevations, the Cruz de Taborno reaches a height of 1,024 metres (3,360 feet). Due to the age of its material (5.7 million years), its deep erosive processes, and the dense network of dikes piercing the massif, its surface exposes numerous outcroppings of both phonolitic and trachytic origin. A large number of steep-walled gorges are present, penetrating deeply into the terrain. Vertical cuts dominate the Anagan coast, with infrequent beaches of rocks or black sand between them; the few that exist generally coincide with the mouths of gorges.[34][78][52]

The Teno massif (Macizo de Teno) is located on the northwestern edge of the island. Like Anaga, it includes an area of outcroppings and deep gorges formed by erosion. However, the materials here are older (about 7.4 million years old). Mount Gala represents its highest elevation at 1,342 metres (4,403 feet). The most unusual landscape of this massif is found on its southern coast, where the Acantilados de Los Gigantes ("Cliffs of the Giants") present vertical walls reaching heights of 500 metres (1,600 feet) in some places.[34][78][52]

The Adeje massif (Macizo de Adeje) is situated on the southern tip of the island. Its main landmark is the Roque del Conde ("Count's Rock"), with an elevation of 1,001 metres (3,284 feet). This massif is not as impressive as the others due to its diminished initial structure, since in addition to with the site's greater geologic age it has experienced severe erosion of its material, thereby losing its original appearance and extent.[34][78][52]

Dorsals

editThe Dorsal mountain ridge or Dorsal of Pedro Gil covers the area from the start at Mount La Esperanza, at a height of about 750 m (2,461 ft), to the center of the island, near the Caldera de Las Cañadas, with Izaña, as its highest point at 2,390 m (7,841 ft) (MSLP). These mountains have been created due to basaltic fissural volcanism through one of the axis that gave birth to the vulcanism of this area.[34][78][52]

The Abeque Dorsal was formed by a chain of volcanoes that join the Teno with the central insular peak of Teide-Pico Viejo starting from another of the three axis of Tenerife's geological structures. On this dorsal we find the historic volcano of Chinyero whose last eruption happened in 1909.[34][78][52]

The South Dorsal or Dorsal of Adeje is part of the last of the structural axis. The remains of this massive rock show the primordial land, also showing the alignment of small volcanic cones and rocks around this are in Tenerife's South.[34][78][52]

Valleys and ravines

editValleys are another of the island's features. The most important are Valle de La Orotava and Valle de Güímar, both formed by the mass sliding of great quantities of material towards the sea, creating a depression of the land. Other valleys tend to be between hills formed by deposits of sediments from nearby slopes, or simply wide ravines which in their evolution have become typical valleys.[34][78][52]

Tenerife has a large number of ravines, which are a characteristic element of the landscape, caused by erosion from surface runoff over a long period. Notable ravines include Ruiz, Fasnia and Güímar, Infierno, and Erques, all of which have been designated protected natural areas by Canarian institutions.[34][78][52]

Coastline

editThe coasts of Tenerife are typically rugged and steep, particularly on the north of the island. However, the island has 67.14 kilometres (41.72 miles) of beaches, such as the one at El Médano, surpassed only in this respect by the island of Fuerteventura.[84] There are many black sand pebble beaches on the northern coast, while on the south and south-west coast of the island, the beaches have typically much finer and clearer sand with lighter tones.[34][78][52]

Volcanic tubes

editLava tubes are volcanic caves usually in the form of tunnels formed within lava flows more or less fluid reogenética duration of the activity. Among the many existing volcanic tubes on the island stands out the Cueva del Viento, located in the northern town of Icod de los Vinos, which is the largest volcanic tunnel in the European Union and one of the largest in the world, for a long time considered the largest in the world.

Flora and fauna

editThe island of Tenerife has a remarkable ecosystem diversity in spite of its small surface area, which is a consequence of the special environmental conditions on the island, where its distinct orography modifies the general climatic conditions at a local level, producing a significant variety of microclimates. This diversity of microclimates allows some 1400 species of plants to exist on the island, with well over 100 of these endemic to Tenerife.[85] The fauna of Tenerife includes some 400 species of fish, 56 birds, five reptiles, two amphibians, 13 land mammals, thousands of invertebrates, and several species of sea turtles and cetaceans.

The vegetation of Tenerife can be divided into six major zones that are directly related to altitude and the direction in which they face.

- Lower xerophytic zone: 0–700 metres (0–2,297 feet). Xerophytic shrubs that are well adapted to long dry spells, intense sunshine and strong winds. Many endemic species: spurges, cactus spurge (Euphorbia canariensis), wax plants (Ceropegia spp.), etc.

- Thermophile forest: 200–600 metres (660–1,970 feet). Transition zone with moderate temperatures and rainfall, but the area has been deteriorated by human activity. Many endemic species: juniper (Juniperus cedrus), dragon trees (Dracaena draco), palm trees (Phoenix canariensis), etc.

- Laurel forest: 500–1,000 metres (1,600–3,300 feet). Dense forest of large trees, descendants of tertiary age flora, situated in a zone of frequent rainfall and mists. A wide variety of species with abundant undergrowth of bushes, herbaceous plants, and ferns. Laurels, holly (Ilex canariensis), ebony (Persea indica), mahogany (Apollonias barbujana), etc.

- Wax myrtle: 1,000–1,500 metres (3,300–4,900 feet). A dryer vegetation, poorer in species. It replaces the degraded laurel forest. Of great forestry importance. Wax myrtles (Myrica faya), tree heath (Erica arborea), holly, etc.

- Pine forest: 800–2,000 metres (2,600–6,600 feet). Open pine forest, with thin and unvaried undergrowth. Canary Island pine (Pinus canariensis), broom (Genista canariensis), rock rose (Cistus spp.), etc.

- High mountain: over 2,000 metres (6,600 feet). Dry climate, intense solar radiation and extreme temperatures. Flora well adapted to the conditions.[85]

Prehistoric fauna

editBefore the arrival of humans, the Canary Islands were inhabited by certain endemic animals, now mostly extinct. These animals reached larger than usual sizes, because of a phenomenon called island gigantism. Among these species, the best known in Tenerife were:

- The giant rat (Canariomys bravoi): Fossils mostly dating from the Pliocene and Pleistocene. Its skull reached up to 7 centimeters long, so it could have reached the size of a rabbit, which would make it quite large compared to European species of rats. Tenerife Giant Rat fossils usually occur in caves and volcanic tubes associated with Gallotia goliath.[86]

- The slender-billed greenfinch (Chloris aurelioi), an extinct greenfinch from the Holocene.[87]

- The long-legged bunting (Emberiza alcoveri), a flightless bunting with long legs and short wings known from Pleistocene to Holocene cave deposits, and one of the few flightless passerines known to science, all of which are now extinct.[88]

- The giant lizard (Gallotia goliath) inhabited Tenerife from the Holocene until the fifteenth century AD. It was a specimen reaching a length of 120 to 125 centimeters (47.2 to 49.2 inches).[89]

- The giant tortoise (Geochelone burchardi): A large tortoise, similar to those currently found in some oceanic islands like the Galápagos Islands in the Pacific Ocean and the Seychelles in the Indian Ocean. Remains found date from the Miocene; this tortoise may have inhabited the island until the Upper Pleistocene, apparently becoming extinct because of volcanic events long before the arrival of humans. Its shell measured approximately 65 to 94 centimetres (26 to 37 inches).[90]

Protected natural areas

editNearly half of the island territory (48.6 percent),[91] is under protection from the Red Canaria de Espacios Naturales Protegidos (Canary Islands Network for Protected Natural Areas). Of the 146 protected sites under control of network in the Canary Islands archipelago,[92] a total of 43 are located in Tenerife, the most protected island in the group.[93] The network has criteria which places areas under its observation under eight different categories of protection, all of them are represented in Tenerife. Aside from Parque Nacional del Teide, it counts the Parque Natural de Canarias (Crown Forest), two rural parks (Anaga and Teno), four integral natural reserves, six special natural reserves, a total of fourteen natural monuments, nine protected landscapes and up to six sites of scientific interest. Also located on the island Macizo de Anaga since 2015 is Biosphere Reserve[17] and is the place that has the largest number of endemic species in Europe.[17]

In contrast to the land-based protected areas, Tenerife also boasts significant marine protected natural areas. Among these is the Zona de Especial Conservación Teno-Rasca (Teno-Rasca Special Area of Conservation), a marine protected area established in 2013.[94] This marine protected area off the coast of Tenerife is known for its ecological significance and biodiversity, including resident populations of cetaceans such as bottlenose dolphins and pilot whales.[95] It is also known as the Tenerife-La Gomera Marine Area and became the first European designated Whale Heritage Area in January 2021.[96]

Administration

editLaw and order

editTenerife island's government resides with the Cabildo Insular de Tenerife[97] located at the Plaza de España at the island's capital city (Palacio Insular de Tenerife). The political Canary organization does not have a provincial government body but instead each island has its own government at their own Cabildo. Since its creation in March 1913 it has a series of capabilities and duties, stated in the Canary Autonomy Statutes (Spanish: Estatuto de Autonomía de Canarias) and regulated by Law 14/1990, of 26 July 1990, of the Régimen Jurídico de las Administraciones Públicas de Canarias.[98]

The Cabildo is composed of the following administrative offices; Presidency, Legislative Body, Government Council, Informative Commissions, Spokesman's office.

Government

editTenerife is an autonomous territory of Spain. The island has a tiered-government system and a special status within the European Union in which it holds lower tax rates compared to other regions. Santa Cruz is the seat of half of the regional government departments and parliament and it is there that the governor is elected by the Canarian people. Afterwards, they are appointed by Madrid. There are fifteen members of parliament who work together in passing legislation, organising budgets and improving the economy.[99]

Municipalities

editThe island, itself part of a Spanish province named Santa Cruz de Tenerife, is divided administratively into 31 municipalities.

Only three municipalities are landlocked: Tegueste, El Tanque and Vilaflor. Vilaflor is the municipality with the highest altitude in the Canaries (its capital is 1,400 metres (4,600 ft) high).

The largest municipality with an area of 207.31 square kilometres (80.04 square miles) is La Orotava, which covers much of the Teide National Park. The smallest town on the island and of the archipelago is Puerto de la Cruz, with an area of just 8.73 square kilometres (3 square miles).[75]

It is also common to find internal division, in that some cities make up a metropolitan area within a municipality, notably the cities of Santa Cruz and La Laguna.

Below is an alphabetical list of all the municipalities on the island:

| Name | Area (km2) |

Census Population | Estimated Population (2023)[100] | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2001[101] | 2011[102] | 2021[103] | |||

| Adeje | 105.95 | 20,255 | 42,886 | 48,822 | 50,523 |

| Arafo | 33.92 | 4,995 | 5,509 | 5,593 | 5,760 |

| Arico | 178.76 | 5,824 | 7,688 | 8,343 | 9,049 |

| Arona | 81.79 | 40,826 | 75,484 | 83,097 | 86,497 |

| Buenavista del Norte | 67.42 | 4,972 | 4,827 | 4,765 | 4,720 |

| Candelaria | 49.18 | 14,247 | 25,928 | 28,614 | 28,876 |

| Fasnia | 45.11 | 2,407 | 2,961 | 2,821 | 2,991 |

| Garachico | 29.28 | 5,307 | 5,035 | 4,921 | 4,975 |

| Granadilla de Abona | 162.40 | 21,135 | 41,209 | 52,401 | 55,505 |

| La Guancha | 23.77 | 5,193 | 5,422 | 5,528 | 5,562 |

| Guía de Isora | 143.40 | 14,982 | 19,734 | 21,871 | 22,478 |

| Güímar | 102.90 | 15,271 | 18,244 | 21,001 | 21,558 |

| Icod de los Vinos | 95.90 | 21,748 | 23,314 | 23,492 | 24,117 |

| La Matanza de Acentejo | 14.11 | 7,053 | 8,677 | 9,134 | 9,114 |

| La Orotava | 207.31 | 37,738 | 41,552 | 42,546 | 42,667 |

| Puerto de la Cruz | 8.73 | 26,441 | 31,349 | 30,326 | 31,396 |

| Los Realejos | 57.08 | 33,438 | 37,517 | 37,256 | 37,543 |

| El Rosario | 39.43 | 13,462 | 17,247 | 17,559 | 17,905 |

| San Cristóbal de La Laguna | 102.60 | 128,822 | 152,025 | 158,117 | 159,576 |

| San Juan de la Rambla | 20.67 | 4,782 | 5,042 | 4,892 | 4,939 |

| San Miguel de Abona | 42.04 | 8,398 | 16,465 | 22,057 | 23,007 |

| Santa Cruz de Tenerife | 150.56 | 188,477 | 204,476 | 208,103 | 208,906 |

| Santa Úrsula | 22.59 | 10,803 | 14,079 | 15,043 | 15,282 |

| Santiago del Teide | 52.21 | 9,303 | 10,689 | 11,101 | 12,072 |

| El Sauzal | 18.31 | 7,689 | 8,988 | 8,938 | 9,161 |

| Los Silos | 24.23 | 5,150 | 4,909 | 4,694 | 4,677 |

| Tacoronte | 30.09 | 20,295 | 23,623 | 24,365 | 24,701 |

| El Tanque | 23.65 | 2,966 | 2,814 | 2,862 | 2,810 |

| Tegueste | 26.41 | 9,417 | 10,908 | 11,346 | 11,375 |

| La Victoria de Acentejo | 18.36 | 7,920 | 8,947 | 9,172 | 9,223 |

| Vilaflor de Chasna | 56.26 | 1,718 | 1,785 | 1,790 | 1,850 |

| Totals | 2,034.42 | 701,034 | 879,303 | 930,570 | 948,815 |

Counties

editThe counties of Tenerife have no official recognition, but there is a consensus among geographers about them:[104]

- Abona

- Acentejo

- Anaga

- Valle de Güímar

- Icod

- Isora

- Valle de La Orotava

- Teno

Flags and heraldry

editThe Flag of Tenerife was originally adopted in 1845 by the navy at its base in the Port of Santa Cruz de Tenerife. Later, and at present, this flag represents all the island of Tenerife. It was approved by the Cabildo Insular de Tenerife and the Order of the Government of the Canary Islands on 9 May 1989 and published on 22 May in the government report of the Canary Islands and made official.[105]

The coat-of-arms of Tenerife was granted by royal decree on 23 March 1510 by Ferdinand II at Madrid in the name of Joan I, Queen of Castile. The coat-of-arms has a field of gold, with an image of Saint Michael (patron saint of the island) above a mountain depicted in brownish, natural colors. Flames erupt from the mountain, symbolizing El Teide. Below this mountain is depicted the island itself in vert on top of blue and silver waves. To the right there is a castle in gules, and to the left, a lion rampant in gules. The shield that the Cabildo Insular, or Island Government, uses is slightly different from that used by the city government of La Laguna, which uses a motto in the arms' border and also includes some palm branches.[106]

Natural symbols

editThe official natural symbols associated with Tenerife are the bird blue chaffinch (Fringilla teydea) and the Canary Islands dragon tree (Dracaena draco) tree.[107]

Demographics

edit| Foreign nationalities (2018)[108] | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Position | Nationality | Population | |||||

| 1 | Venezuela | 42,586 | |||||

| 2 | Italy | 19,224 | |||||

| 3 | Cuba | 17,745 | |||||

| 4 | United Kingdom | 12,321 | |||||

| 5 | Germany | 9,590 | |||||

| 6 | Colombia | 8,188 | |||||

| 7 | Argentina | 8,104 | |||||

| 8 | Morocco | 5,656 | |||||

| 9 | Uruguay | 4,773 | |||||

| 10 | China | 3,832 | |||||

| 11 | Romania | 3,761 | |||||

| 12 | France | 3,490 | |||||

| 13 | Belgium | 2,760 | |||||

| 14 | India | 2,404 | |||||

| 15 | Ecuador | 2,073 | |||||

According to INE data as at 1 January 2023, Tenerife has the largest population of the seven Canary Islands and was the most populated island of Spain with 948,815 officially estimated inhabitants,[6] of whom about 22.0 percent (208,906) lived in the capital, Santa Cruz de Tenerife, and 40 percent in the metropolitan area of Santa Cruz–La Laguna.[109] Santa Cruz de Tenerife and the city of San Cristóbal de La Laguna are physically one urban area, so that together (and including Tegueste) they have a population of 379,857 inhabitants.[110][111]

Tenerife has two other metropolitan areas recognized by the Ministry of Development; the Tenerife South metropolitan area with 194,774 inhabitants (2019) and the La Orotava Valley metropolitan area with 108,721 inhabitants (2019).[112]

After the city of Santa Cruz the major towns and municipalities as at the start of 2023 are San Cristóbal de La Laguna (159,576), Arona (86,497), Granadilla de Abona (55,505), Adeje (50,523), La Orotava (42,667), Los Realejos (37,543), and Puerto de la Cruz (31,396). All other municipalities have fewer than 30,000 inhabitants, the smallest municipality being Vilaflor with a population of 1,850.

The island has high rates of resident population not registered in population censuses, primarily tourists. This has made several sources point out that more than one million inhabitants actually live on the island of Tenerife today.[113] The island is also the most multicultural in the archipelago, with the highest number of registered foreigners (44.9% of registered in Canary Islands), which represent 14% of the total population of the island.[114] Tenerife stands out in the context of the archipelago, by also concentrating the largest presence of non-EU foreign population.[115]

Tenerife has three large population areas that are very different and distributed: The Metropolitan Zone, the South Zone and the North Zone. With several protected natural parks — 48.6% of the territory — and an urban swarm around the island, in the last half century the insular coastal platform has become a highly urbanized metropolitan system. The high level of population in a relatively small territory — more than 900,000 inhabitants in just over 2,000 km2 (770 sq mi) — and the strong urbanization have turned the island of Tenerife, in the words of architect Federico García Barba; on an "island-city" or "island-ring".[116][117]

Recently Tenerife has experienced population growth significantly higher than the national average. In 1990, there were 663,306 registered inhabitants, which increased to 709,365 in 2000, an increase of 46,059 or an annual growth of 0.69 percent. However, between 2000 and 2007, the population rose by 155,705 to 865,070, an annual increase of 3.14 percent.[118]

These results reflect the general trend in Spain where, since 2000, immigration has reversed the general slowdown in population growth, following the collapse in the birth rate from 1976. However, since 2001 the overall growth rate in Spain has been around 1.7 percent per year, compared with 3.14 percent on Tenerife, one of the largest increases in the country.[119]

Economy

editTenerife is the economic capital of the Canary Islands.[120] At present, Tenerife is the island with the highest GDP in the Canary Islands.[121] Even though Tenerife's economy is highly specialized in the service sector, which makes 78% of its total production capacity, the importance of the rest of the economic sectors is key to its production development. In this sense, the primary sector, which only represents 1.98% of the total product, groups activities that are important to the sustainable development of the island's economy. The energy sector which contributes 2.85% has a primary role in the development of renewable energy sources. The industrial sector which shares in 5.80% is a growing activity in the island, vis-a-vis the new possibilities created by technological advances. Finally, the construction sector with 11.29% of the total production has a strategic priority, because it is a sector with relative stability which permits multiple possibilities of development and employment opportunities.[122]

Tourism

editTourism is the most prominent industry in the Canaries, which are one of the major tourist destinations in the world. Tenerife is the most visited island in the archipelago[8] and one of the most important tourist destinations in Spain.[9]

In 2014, 11,473,600 foreign tourists came to the Canary Islands. Tenerife had 4,171,384 arrivals that year, excluding the numbers for Spanish tourists which make up an additional 30% of total arrivals. According to last year's Canarian Statistics Centre's (ISTAC) Report on Tourism the greatest number of tourists from any one country come from the United Kingdom, with more than 3,980,000 tourists in 2014. In second place comes Germany followed by Sweden, Norway, the Netherlands, France, Ireland, Belgium, Italy, Denmark, Finland, Switzerland, Poland, Russia and Austria.[citation needed]

Tourism is more prevalent in the south of the island, which is hotter and drier and has many well developed resorts such as Playa de las Americas and Los Cristianos. More recently coastal development has spread northwards from Playa de las Americas and now encompasses the former small enclave of La Caleta. According to the Moratoria act passed by the Canarian Parliament in Santa Cruz de Tenerife, no more hotels will be built on the island unless they are classified as 5 star-quality and comprise different services such as golf courses or convention facilities. This act was passed with the goal of improving the standard of tourism service and promoting environmentally conscious development.

The area known as Costa Adeje has many facilities and leisure opportunities such as shopping centres, golf courses, restaurants, water parks (the most well-known being Siam Park), animal parks, and a theatre suitable for musicals or a convention centre.[123] There are many boats offering whale watching tours from the harbour of Puerto Colon. The deep waters off the coast of Costa Adeje are home to several pods of pilot whales.[124]

In the more lush and green north of the island, the main focus of development for tourism has been in the town of Puerto de la Cruz. Puerto de la Cruz is home to the SeaWorld-owned zoo, Loro Parque,[125] which has been accused of mistreatment of animals in its captivity, including orcas[126] and is currently boycotted by major travel agents including Thomas Cook.[127]

In the 19th century large numbers of foreign tourists came, especially British, showing interest in the agriculture of the islands. With the world wars, the tourism sector weakened, but the second half of the 20th century brought renewed interest. Initial emphasis was on Puerto de la Cruz, and for all the attractions that the Valle de la Orotava offered. By 1980, tourism was focused in south Tenerife. The emphasis was on cities like Arona or Adeje, shifting to tourist centres like Los Cristianos or Playa de Las Americas, which now house 65% of the hotels on the island. Tenerife receives more than 5 million tourists every year; of the Сanary islands Tenerife is the most popular.[34] [128]

Currently, the municipality of Adeje in the south of the island has the highest concentration of 5 star hotels in Europe[129] and also has what is considered the best luxury hotel in Spain according to World Travel Awards.[130]

Agriculture and fishing

editSince tourism dominates the Tenerifan economy, the service sector is the largest. Industry and commerce contribute 40% of the non-tourist economy.[131] Agriculture contributes less than 10% of the island's GDP, but its contribution is vital as it also generates indirect benefits by maintaining the rural appearance of the island and supporting Tenerifan cultural values.

Agriculture is centred on the northern slopes, and is affected by altitude as well as orientation: in the coastal zone, tomatoes and bananas are cultivated, these high yield products are for export to mainland Spain and the rest of Europe; in the drier intermediate zone, potatoes, tobacco and maize are grown, whilst in the south, onions are important.[34]

Bananas are a particularly important crop, as Tenerife grows more bananas than the other Canary Islands, with a current annual production of about 150,000 tons, down from the peak production of 200,000 tons in 1986. More than 90% of the total is destined for the international market, and banana growing occupies about 4200 hectares.[132] After the banana the most important crops are, in order of importance, tomatoes, grapes, potatoes and flowers. Fishing is also a major contributor to the Tenerifan economy, as the Canaries are Spain's second most important fishing grounds.

Energy

editAs of 2009, Tenerife had 910 MW of electrical generation capacity, which is mostly powered from petroleum-derived fuels. The island had 37 MW of wind turbines and 79 MW of solar panels.[133]

Industry and commerce

editCommerce in Tenerife plays a significant role in the economy, representing almost 20% of the GDP, with the commercial center Santa Cruz de Tenerife generating most of the earnings. Although there are a diversity of industrial estates that exist on the island, the most important industrial activity is petroleum, representing 10% of the island's GDP, again largely due to the capital Santa Cruz de Tenerife with its refinery. It provides petroleum products not only to the Canaries archipelago but is also an active in the markets of the Iberian Peninsula, Africa and South America.

Main sights

editMonuments

editHistorical sights in the island, especially from the time after the conquest, include the Cathedral of San Cristóbal de La Laguna, the Church of the Conception of La Laguna and the Church of the Conception in the capital. The Basílica de Nuestra Senora de la Candelaria can be found on the island (Patron of Canary Islands). Also on the island are the defensive castles located in the village of San Andrés, as well as many others throughout the island.

The Auditorio de Tenerife, one of the most modern in Spain, can be found at the entry port to the capital (in the southern part of Port of Santa Cruz de Tenerife). Near the Auditorio de Tenerife are El Castillo Negro and El Parque Marítimo. The Torres de Santa Cruz are two twin skyscrapers 120 metres (390 feet) high (the highest residential buildings in Spain and the tallest skyscrapers in the Canary Islands).[134]

Archeological sites

editThe island also has several archaeological sites of Guanche time (prior to the conquest), which generally are cave paintings that are scattered throughout the island, but most are found in the south of the island.

Archaeological sites on the island include the Cave of the Guanches, where the oldest remains in the archipelago have been found,[135] dating to the 6th century BC,[136] and the Caves of Don Gaspar, where the finding of plant debris in the form of carbonized seeds indicates that the Guanches practiced agriculture on the island.[135] Both deposits are in the town of Icod de los Vinos. Also noteworthy on the island is the Estación solar de Masca (Masca Solar Station), which was an aboriginal sanctuary for the celebration of rites related to fertility and the request for rainwater. This is located in the municipality of Buenavista del Norte.

Other archaeological sites include that of Los Cambados and that of El Barranco del Rey both in Arona.[137] One could also highlight the Cueva de Achbinico (first shrine Marian of the Canary Islands, Guanche vintage-Spanish). In addition there are some buildings called Güímar Pyramids, whose origin is uncertain.

There are also traces that reveal the Punic presence on the island, as in the wake commonly called "Stone of the Guanches" in the town of Taganana. This archaeological site consists of a structure formed by a stone block, large, outdoor, featuring rock carvings on its surface. Among these is the presence of a representation of the Carthaginian goddess Tanit,[138] represented by a bottle-shaped symbol surrounded by cruciform motifs. It is thought that the monument was originally an altar of sacrifice linked to those found in the Semitic[138] field and then reused for Aboriginal ritual of mummification.[138]

Culture and arts

editLiterature

editIn the 16th and 17th centuries, Antonio de Viana, a native of La Laguna, composed the epic poem Antigüedades de las Islas Afortunadas (Antiquities of the Fortunate Isles), a work of value to anthropologists, since it sheds light on Canarian life of the time.[139] The Enlightenment reached Tenerife, and literary and artistic figures of this era include José Viera y Clavijo, Tomás de Iriarte y Oropesa, Ángel Guimerá y Jorge, Mercedes Pinto and Domingo Pérez Minik, amongst others.

Painting

editDuring the course of the 16th century, several painters flourished in La Laguna, as well as in other places on the island, including Garachico, Santa Cruz de Tenerife, La Orotava and Puerto de la Cruz. Cristóbal Hernández de Quintana and Gaspar de Quevedo, considered the best Canarian painters of the 17th century, were natives of La Orotava, and their art can be found in churches on Tenerife.[140]

The work of Luis de la Cruz y Ríos can be found in the church of Nuestra Señora de la Peña de Francia, in Puerto de la Cruz. Born in 1775, he became court painter to Ferdinand VII of Spain and was also a miniaturist, and achieved a favorable position in the royal court. He was known there by the nickname of "El Canario."[141]

The landscape painter Valentín Sanz (born 1849) was a native of Santa Cruz de Tenerife, and the Museo Municipal de Bellas Artes de Santa Cruz displays many of his works. This museum also contains the works of Juan Rodríguez Botas (1880–1917), considered the first Canarian impressionist.[142]

Frescoes by the expressionist Mariano de Cossío can be found in the church of Santo Domingo, in La Laguna. The watercolorist Francisco Bonnín Guerín (born 1874) was a native of Santa Cruz, and founded a school to encourage the arts. Óscar Domínguez was born in La Laguna in 1906 and is famed for his versatility. He belonged to the surrealist school, and invented the technique known as decalcomania.[143]

Sculpture

editThe arrival from Seville of Martín de Andújar Cantos, an architect and sculptor brought new sculpting techniques of the Seville school, which were passed down to his students, including Blas García Ravelo, a native of Garachico. He had been trained by the master sculptor Juan Martínez Montañés.[144]

Other notable sculptors from the 17th and 18th centuries include Sebastián Fernández Méndez, Lázaro González de Ocampo, José Rodríguez de la Oliva, and most importantly, Fernando Estévez, a native of La Orotava and a student of Luján Pérez. Estévez contributed an extensive collection of religious images and woodcarvings, found in numerous churches of Tenerife, such as the Principal Parish of Saint James the Great (Parroquia Matriz del Apóstol Santiago), in Los Realejos; in the Cathedral of La Laguna; the Iglesia de la Concepción in La Laguna; the basilica of Candelaria, and various churches in La Orotava.

Music