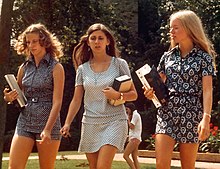

Youth is the time of life when one is young. The word, youth, can also mean the time between childhood and adulthood (maturity), but it can also refer to one's peak, in terms of health or the period of life known as being a young adult.[1][2] Youth is also defined as "the appearance, freshness, vigor, spirit, etc., characteristic of one, who is young".[3] Its definitions of a specific age range varies, as youth is not defined chronologically as a stage that can be tied to specific age ranges; nor can its end point be linked to specific activities, such as taking unpaid work, or having sexual relations.[4][5]

Youth is an experience that may shape an individual's level of dependency, which can be marked in various ways according to different cultural perspectives. Personal experience is marked by an individual's cultural norms or traditions, while a youth's level of dependency means the extent to which they still rely on their family emotionally and economically.[4]

Terminology and definitions

editGeneral

editAround the world, the English terms youth, adolescent, teenager, kid, youngster and young person often mean the same thing,[6] but they are occasionally differentiated. Youth can be referred to as the time of life, when one is young. The meaning may in some instances also include childhood.[7][8] Youth also identifies a particular mindset of attitude, as in "He is very youthful". For certain uses, such as employment statistics, the term also sometimes refers to individuals from the ages of up to 21.[9] However, the term adolescence refers to a specific age range during a specific developmental period in a person's life, unlike youth, which is a socially constructed category.[4]

The United Nations defines youth as persons between the ages of roughly 12 and 24, with all UN statistics based on this range, the UN states education as a source for these statistics. The UN also recognizes that this varies without prejudice to other age groups listed by member states such as 18–30. A useful distinction within the UN itself can be made between teenagers (i.e. those between the ages of 13 and 19) and young adults (those between the ages of 20 and 24). While seeking to impose some uniformity on statistical approaches, the UN is aware of contradictions between approaches in its own statutes. Hence, under the 15–24 definition (introduced in 1981) children are defined as those under the age of (someone 12 and younger) while under the 1979 Convention on the Rights of the Child, those under the age of 18 are regarded as children.[10] The UN also states they are aware that several definitions exist for youth within UN entities such as Youth Habitat 15–32, NCSL 12-24, and African Youth Charter 15–35.

On November 11, 2020, the State Duma of the Russian Federation approved a project to raise the cap on the age of young people from 30 to 35 years (the range now extending from 14 to 35 years).[11]

Although linked to biological processes of development and aging, youth is also defined as a social position that reflects the meanings different cultures and societies give to individuals between childhood and adulthood. The term in itself when referred to in a manner of social position can be ambiguous when applied to someone of an older age with very low social position; potentially when still dependent on their guardians.[12] Scholars argue that age-based definitions have not been consistent across cultures or times and that thus it is more accurate to focus on social processes in the transition to adult independence for defining youth.[13]

- "This world demands the qualities of youth: not a time of life but a state of mind, a temper of the will, a quality of imagination, a predominance of courage over timidity, of the appetite for adventure over the life of ease." – Robert Kennedy[14]

Youth is the stage of constructing the self-concept. The self-concept of youth is influenced by variables such as peers, lifestyle, gender, and culture.[15] It is a time of a person's life when their choices are most likely to affect their future.[16][17]

Other definitions

editIn much of sub-Saharan Africa, the term "youth" is associated with young men from 12 to 30 or 35 years of age. Youth in Nigeria includes all members of the Federal Republic of Nigeria aged 18–35.[18] Many African girls experience youth as a brief interlude between the onset of puberty and marriage and motherhood. But in urban settings, poor women are often considered youth much longer, even if they bear children outside of marriage. Varying culturally, the gender constructions of youth in Latin America and Southeast Asia differ from those of sub-Saharan Africa. In Vietnam, widespread notions of youth are sociopolitical constructions for both sexes between the ages of 15 and 35.[19]

In Brazil, the term youth refers to people of both sexes from 15 to 29 years old. This age bracket reflects the influence on Brazilian law of international organizations like the World Health Organization (WHO). It is also shaped by the notion of adolescence that has entered everyday life in Brazil through a discourse on children's rights.[19]

The OECD defines youth as "those between 15 and 29 years of age".[20][21]

August 12 was declared International Youth Day by the United Nations.

Youth rights

editChildren's rights cover all the rights that belong to children. When they grow up, they are granted new rights (like voting, consent, driving, etc.) and duties (criminal response, etc.). There are different minimum limits of age at which youth are not free, independent or legally competent to take some decisions or actions. Some of these limits are: voting age, age of candidacy, age of consent, age of majority, age of criminal responsibility, drinking age, driving age, etc. After youth reach these limits, they are free to vote, have sexual intercourse, buy or consume alcoholic beverages or drive cars, etc.

Voting age

editVoting age is the minimum age established by law that a person must attain to be eligible to vote in a public election. Typically, the age is set at 18 years; however, ages as low as 16 and as high as 21 exist (see list below). Studies show that 21% of all 18-year-olds have experience with voting. This is an important right since, by voting, they can support politics selected by themselves and not only by people of older generations.

Age of candidacy

editAge of candidacy is the minimum age at which a person can legally qualify to hold certain elected government offices. In many cases, it also determines the age at which a person may be eligible to stand for an election or be granted ballot access.

Age of consent

editThe age of consent is the age at which a person is considered legally competent to consent to sexual acts, and is thus the minimum age of a person with whom another person is legally permitted to engage in sexual activity. The distinguishing aspect of the age of consent laws is that the person below the minimum age is regarded as the victim, and their sex partner as the offender.

Defense of infancy

editThe defense of infancy is a form of defense known as an excuse so that defendants falling within the definition of an "infant" are excluded from criminal liability for their actions, if at the relevant time, they had not reached an age of criminal responsibility. This implies that children lack the judgment that comes with age and experience to be held criminally responsible. After reaching the initial age, there may be levels of responsibility dictated by age and the type of offense committed.

Drinking age

editThe legal drinking age is the age at which a person can consume or purchase alcoholic beverages. These laws cover a wide range of issues and behaviors, addressing when and where alcohol can be consumed. The minimum age alcohol can be legally consumed can be different from the age when it can be purchased in some countries. These laws vary among different countries and many laws have exemptions or special circumstances. Most laws apply only to drinking alcohol in public places, with alcohol consumption in the home being mostly unregulated (an exception being the UK, which has a minimum legal age of five for supervised consumption in private places). Some countries also have different age limits for different types of alcoholic drinks.[22]

Driving age

editDriving age is the age at which a person can apply for a driver's license. Countries with the lowest driving ages (below 17) are Argentina, Australia, Canada, El Salvador, Iceland, Israel, Macedonia, Malaysia, New Zealand, the Philippines, Saudi Arabia, Slovenia, the United Kingdom (Mainland) and the United States. The Canadian province of Alberta and several U.S. states permit youth driving as low as 14. Niger has the highest minimum driving age in the world at 23. In India, driving is legal after getting a license at the age of 18.

Legal working age

editThe legal working age is the minimum age required by law for a person to work in each country or jurisdiction. The threshold of adulthood, or "the age of majority" as recognized or declared in law in most countries, has been set at age 18. Some types of labor are commonly prohibited even for those above the working age, if they have not reached the age of majority. Activities that are dangerous, harmful to the health or that may affect the morals of minors fall into this category.

Student rights in higher education

editStudent rights are those rights, such as civil, constitutional, contractual and consumer rights, which regulate student rights and freedoms and allow students to make use of their educational investment. These include such things as the right to free speech and association, to due process, equality, autonomy, safety and privacy, and accountability in contracts and advertising, which regulate the treatment of students by teachers and administrators.

Smoking age

editThe smoking age is the minimum age a person can buy tobacco and/or smoke in public. Most countries regulate this law at the national level while at some point it is done by the state or province.

School and education

editYoung people spend much of their lives in educational settings, and their experiences in schools, colleges and universities can shape much of their subsequent lives.[23] Research shows that poverty and income affect the likelihood for the incompletion of high school. These factors also increase the likelihood for the youth to not go to a college or university.[24] In the United States, 12.3 percent of young people ages 16 to 24 are disconnected, meaning they are neither in school nor working.[25]

Health and mortality

editThe leading causes of morbidity and mortality among youth and adults are due to certain health-risk behaviors. These behaviors are often established during youth and extend into adulthood. Since the risk behaviors in adulthood and youth are interrelated, problems in adulthood are preventable by influencing youth behavior.

A 2004 mortality study of youth (defined in this study as ages 10–24) mortality worldwide found that 97% of deaths occurred in low to middle-income countries, with the majority in southeast Asia and sub-Saharan Africa. Maternal conditions accounted for 15% of female deaths, while HIV/AIDS and tuberculosis were responsible for 11% of deaths; 14% of male and 5% of female deaths were attributed to traffic accidents, the largest cause overall. Violence accounted for 12% of male deaths. Suicide was the cause of 6% of all deaths.[26]

The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention developed its Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance System (YRBSS) in 2003 to help assess risk behavior.[27] YRBSS monitors six categories of priority health-risk behaviors among youth and young adults. These are behaviors that contribute to unintentional injuries and violence;

- tobacco, alcohol and other drug use;

- sexual behaviors that contribute to unintended pregnancy and sexually transmitted diseases (STDs), including human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection;

- unhealthy dietary behaviors;

- physical inactivity—plus overweight.

YRBSS includes a national school-based survey conducted by CDC as well as state and local school-based surveys conducted by education and health agencies.[28]

Universal school-based interventions such as formal classroom curricula, behavioural management practices, role‐play, and goal‐setting may be effective in preventing tobacco use, alcohol use, illicit drug use, antisocial behaviour, and improving physical activity of young people.[29]

Diabetes

editType 1 diabetes (T1D) is an autoimmune disease that occurs when pancreatic cells, also called beta cells, are destroyed by the immune system. Beta cells are responsible to produce insulin, which is required by the body to convert blood sugar into energy. Symptoms associated with T1D include frequent urination, increased hunger and thirst, weight loss, blurry vision, and tiredness.[30]

Type 2 diabetes (T2D) is characterized by high blood sugar and insulin resistance. This is not an autoimmune disease and is mostly a result of obesity and lack of exercise.

Exercise is a crucial addition to a child's everyday routine. It can increase the overall psychosocial well-being, metabolic health and cardiovascular benefits. American College of Sports Medicine recommends at least 60 minutes of moderate to vigorous intensity each day. Recommended activities include running, bicycle riding and team sports. Furthermore, at least 3 days of bone and muscle strengthening activities should be incorporated.[31]

Unfortunately, in reality a large percentage of T1D youth population is not meeting this guideline. Common barriers include fear of hypoglycemia, loss of glucose stability, low fitness levels, insufficient or inadequate knowledge of strategies to prevent hypoglycemia, lack of time, and lack of confidence in the topic of exercise management in type 1 diabetes.[31]

Many Health and Care Professions Council members who work with children aren't educated enough about diabetes in children and exercise recommendations. It is important for parents to educate themselves to support their children throughout this chapter of their lives.

Structured exercises lasting longer than 60 minutes can reduce HbA1c levels and insulin dose per day. Moderate activities can increase cardiorespiratory fitness in children which is crucial for their future health. Cardiorespiratory fitness reduces the risk of other diseases, such as microvascular complications and cardiovascular diseases.[32]

To avoid a possible type 2 diabetes, children are encouraged to keep their BMI and adipose tissue percentage at normal levels. Exercising regularly improves insulin resistance, reduces blood glucose levels, and keep an individual at a healthy weight to stay away from a possible T2D diagnosis.[33]

Obesity

editObesity now affects one in five children in the United States, and is the most prevalent nutritional disease of children and adolescents in the United States. Although obesity-associated morbidities occur more frequently in adults, significant consequences of obesity as well as the antecedents of adult disease occur in obese children and adolescents.

Discrimination against overweight children begins early in childhood and becomes progressively institutionalized. Obese children may be taller than their non-overweight peers, in which case they are apt to be viewed as more mature. The inappropriate expectations that result may have an adverse effect on their socialization.

Many of the cardiovascular consequences that characterize adult-onset obesity are preceded by abnormalities that begin in childhood. Hyperlipidemia, hypertension, and abnormal glucose tolerance occur with increased frequency in obese children and adolescents. The relationship of cardiovascular risk factors to visceral fat independent of total body fat remains unclear. Sleep apnea, pseudotumor cerebri, and Blount's disease represent major sources of morbidity for which rapid and sustained weight reduction is essential. Although several periods of increased risk appear in childhood, it is not clear whether obesity with onset early in childhood carries a greater risk of adult morbidity and mortality.[34]

Bullying

editBullying among school-aged youth is increasingly being recognized as an important problem affecting well-being and social functioning. While a certain amount of conflict and harassment is typical of youth peer relations, bullying presents a potentially more serious threat to healthy youth development. The definition of bullying is widely agreed on in literature on bullying.[35][36][37][38]

The majority of research on bullying has been conducted in Europe and Australia.[39] Considerable variability among countries in the prevalence of bullying has been reported. In an international survey of adolescent health-related behaviors, the percentage of students who reported being bullied at least once during the current term ranged from a low of 15% to 20% in some countries to a high of 70% in others.[40][41] Of particular concern is frequent bullying, typically defined as bullying that occurs once a week or more. The prevalence of frequent bullying reported internationally ranges from a low of 1.9% among one Irish sample to a high of 19% in a Malta study.[42][43][44][45][46][47]

Research examining characteristics of youth involved in bullying has consistently found that both bullies and those bullied demonstrate poorer psychosocial functioning than their non-involved peers. Youth who bully others tend to demonstrate higher levels of conduct problems and dislike of school, whereas youth who are bullied generally show higher levels of insecurity, anxiety, depression, loneliness, unhappiness, physical and mental symptoms, and low self-esteem. Males who are bullied also tend to be physically weaker than males in general. The few studies that have examined the characteristics of youth who both bully and are bullied found that these individuals exhibit the poorest psychosocial functioning overall.[48][49][50][51]

Sexual health and politics

editGeneral

editGlobalization and transnational flows have had tangible effects on sexual relations, identities, and subjectivities. In the wake of an increasingly globalized world order under waning Western dominance, within ideologies of modernity, civilization, and programs for social improvement, discourses on population control, 'safe sex', and 'sexual rights'.[52] Sex education programmes grounded in evidence-based approaches are a cornerstone in reducing adolescent sexual risk behaviours and promoting sexual health. In addition to providing accurate information about consequences of Sexually transmitted disease or STIs and early pregnancy, such programmes build life skills for interpersonal communication and decision making. Such programmes are most commonly implemented in schools, which reach large numbers of teenagers in areas where school enrollment rates are high. However, since not all young people are in school, sex education programmes have also been implemented in clinics, juvenile detention centers and youth-oriented community agencies. Notably, some programmes have been found to reduce risky sexual behaviours when implemented in both school and community settings with only minor modifications to the curricula.[53]

Philippines

editThe Sangguniang Kabataan ("Youth Council" in English), commonly known as SK, was a youth council in each barangay (village or district) in the Philippines, before being put "on hold", but not quite abolished, prior to the 2013 barangay elections.[54] The council represented teenagers from 15 to 17 years old who have resided in their barangay for at least six months and registered to vote. It was the local youth legislature in the village and therefore led the local youth program and projects of the government. The Sangguniang Kabataan was an offshoot of the KB or the Kabataang Barangay (Village Youth) which was abolished when the Local Government Code of 1991 was enacted.

In the Global South

editThe vast majority of young people live in developing countries: according to the United Nations, globally around 85 per cent of 15- to 25-year-olds live in developing countries, a figure projected to grow 89.5 per cent by 2025. Moreover, this majority are extremely diverse: some live in rural areas but many inhabit the overcrowded metropolises of India, Mongolia and other parts of Asia and in South America, some live traditional lives in tribal societies, while others participate in global youth culture in ghetto contexts.[55]

Many young lives in developing countries are defined by poverty, some suffer from famine and a lack of clean water, while involvement in armed conflict is all common. Health problems are rife, especially due to the prevalence of HIV/AIDS in certain regions. The United Nations estimates that 200 million young people live in poverty, 130 million are illiterate and 10 million live with HIV/AIDS.[55]

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ "Youth". Macmillan Dictionary. Macmillan Publishers Limited. Retrieved 2013–8–15.

- ^ "Youth". Merriam-Webster. Retrieved November 6, 2012.

- ^ "Youth". Dictionary.com. Retrieved November 6, 2012.

- ^ a b c Furlong, Andy (2013). Youth Studies: An Introduction. USA: Routledge. pp. 2–3. ISBN 978-0-415-56476-2.

- ^ Youth participation in political activities: The art of participation in Bhakkar, Punjab Pakistan, Journal of Human Behavior in the Social Environment, 30:6, 760-777, https://doi.org/10.1080/10911359.2020.1745112

- ^ Konopka, Gisela. (1973) "Requirements for Healthy Development of Adolescent Youth", Adolescence. 8 (31), p. 24.

- ^ "Youth dictionary definition – youth defined".

- ^ Webster's New World Dictionary.

- ^ Altschuler, D.; Strangler, G.; Berkley, K.; Burton, L. (2009); "Supporting Youth in Transition to Adulthood: Lessons Learned from Child Welfare and Juvenile Justice" Archived September 16, 2012, at the Wayback Machine. Center for Juvenile Justice Reform.

- ^ Furlong, Andy (2013). Youth Studies: An Introduction. USA: Routledge. pp. 3–4. ISBN 978-0-415-56476-2.

- ^ Youth in Russia, accessed 12 June 2021

- ^ Furlong, Andy (2011). Youth Studies: An Introduction. New York: Routledge. ISBN 978-0415564793.

- ^ Tyyskä, Vappu (2005). "Conceptualizing and Theorizing Youth: Global Perspectives". Contemporary Youth Research: Local Expressions and Global Connections. London: Ashgate Books. p. 3. ISBN 0-7546-4161-9.

- ^ "Day of Affirmation, University of Cape Town, South Africa. June 6, 1966" Archived February 27, 2011, at the Wayback Machine, Robert F. Kennedy Memorial. Retrieved 11/9/07.

- ^ Thomas, A. (2003) "Psychology of Adolescents", Self-Concept, Weight Issues and Body Image in Children and Adolescents, p. 88.

- ^ Wing, John, Jr. "Youth." Windsor Review: A Journal of the Arts 45.1 (2012): 9+. Academic OneFile. Web. 24 Oct. 2012.

- ^ Saud, Muhammad; Ida, Rachmah; Mashud, Musta’in (2020). "Democratic practices and youth in political participation: a doctoral study". International Journal of Adolescence and Youth. 25 (1): 800–808. doi:10.1080/02673843.2020.1746676.

- ^ "Nigeria 2009 National Youth Policy" (PDF).

- ^ a b Dalsgaard, Anne Line Hansen, Karen Tranberg. "Youth and the City in the Global South" In Tracking Globalization. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. 2008: 9

- ^ OECD.org.OECD work on Youth.

- ^ "Young people not in education or employment" (PDF). OECD Family Database. 2018.

- ^ Drinking Age Limits Archived 2013-01-20 at the Wayback Machine – International Center for Alcohol Policies

- ^ Furlong, Andy (2013). Youth Studies: An Introduction. USA: Routledge. pp. 48–49. ISBN 978-0-415-56476-2.

- ^ Njapa-Minyard, Pamela (2010). "After-school Programs: Attracting and Sustaining Youth Participation". International Journal of Learning. 17 (9): 177–182. Archived from the original on 2017-06-30. Retrieved 2013-08-16.

- ^ Sarah Burd-Sharps and Kristen Lewis. Promising Gains, Persistent Gaps: Youth Disconnection in America. 2017. Measure of America of the Social Science Research Council.

- ^ Patton, George C.; Coffey, Carolyn; Sawyer, Susan M.; Viner, Russell M.; Haller, Dagmar M.; Bose, Krishna; Vos, Theo; Ferguson, Jane; Mathers, Colin D. (September 2009). "Global patterns of mortality in young people: a systematic analysis of population health data". The Lancet. 374 (9693): 881–892. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60741-8. PMID 19748397. S2CID 15161702.

- ^ "Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance System (YRBSS)". Adolescent and School Health. CDC. 22 August 2018.

- ^ Grunbaum, J.A., Kann, L., Kinchen, S., Ross, J., Hawkins, J., Lowry, R., Harris, W.A., McManus, T., Chyen, D., Collins, J. (2004) Youth risk behavior surveillance—United States, 2003. MMWR. Surveillance Summaries, 53(2), 1–96.

- ^ MacArthur G, Caldwell DM, Redmore J, Watkins SH, Kipping R, White J, Chittleborough C, Langford R, Er V, Lingam R, Pasch K, Gunnell D, Hickman M, Campbell R (5 October 2018). "Individual-, family-, and school-level interventions targeting multiple risk behaviours in young people". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2018 (10): CD009927. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD009927.pub2. PMC 6517301. PMID 30288738.

- ^ "Type 1 diabetes", Wikipedia, 2024-11-15, retrieved 2024-11-15[deprecated source]

- ^ a b Chinchilla, P., Dovc, K., Braune, K., Addala, A., Riddell, M. C., Jeronimo Dos Santos, T., & Zaharieva, D. P. (2023). Perceived Knowledge and Confidence for Providing Youth-Specific Type 1 Diabetes Exercise Recommendations amongst Pediatric Diabetes Healthcare Professionals: An International, Cross-Sectional, Online Survey. Pediatric Diabetes, 1–8.

- ^ García-Hermoso, A., Ezzatvar, Y., Huerta-Uribe, N., Alonso-Martínez, A. M., Chueca-Guindulain, M. J., Berrade-Zubiri, S., Izquierdo, M., & Ramírez-Vélez, R. (2023). Effects of exercise training on glycaemic control in youths with type 1 diabetes: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. European Journal of Sport Science, 23(6), 1056–1067.

- ^ Aran Wong. (2024). Role of Physical Activity in the Management and Prevention of Type 2 Diabetes. International Journal of Medicine & Science of Physical Activity & Sport / Revista Internacional de Medicina y Ciencias de La Actividad Física y Del Deporte, 24(96), 166–180

- ^ William, H. (1998) Health Consequences of Obesity in Youth: Childhood Predictors of Adult Disease, Pediatrics, 101(2), 518–525.

- ^ Boulton MJ, Underwood K. Bully/victim problems among middle school children. Br J Educ Psychol.1992;62:73–87.

- ^ Olweus D. Aggression in the Schools: Bullies and Whipping Boys. Washington, DC: Hemisphere Publishing Corp; 1978.

- ^ Salmivalli, C; Kaukiainen, A; Kaistaniemi, L; Lagerspetz, KM (1999). "Self-evaluated self-esteem, peer-evaluated self-esteem, and defensive egotism as predictors of adolescents' participation in bullying situations". Pers Soc Psychol Bull. 25 (10): 1268–1278. doi:10.1177/0146167299258008. S2CID 145521375.

- ^ Slee PT. Bullying in the playground: the impact of inter-personal violence on Australian children's perceptions of their play environment. Child Environ.1995;12:320–327.

- ^ Biswas, Tuhin; Scott, James G.; Munir, Kerim; Thomas, Hannah J.; Huda, M. Mamun; Hasan, Md. Mehedi; David de Vries, Tim; Baxter, Janeen; Mamun, Abdullah A. (2020-02-17). "Global variation in the prevalence of bullying victimisation amongst adolescents: Role of peer and parental supports". eClinicalMedicine. 20: 100276. doi:10.1016/j.eclinm.2020.100276. ISSN 2589-5370. PMC 7152826. PMID 32300737.

- ^ King A, Wold B, Tudor-Smith C, Harel Y. The Health of Youth: A Cross-National Survey. Canada: WHO Library Cataloguing; 1994. WHO Regional Publications, European Series No. 69.

- ^ US Department of Education. 1999 Annual Report on School Safety. Washington, DC: US Dept of Education; 1999:1–66.

- ^ Borg MG. The extent and nature of bullying among primary and secondary schoolchildren. Educ Res.1999;41:137–153.

- ^ Kaltiala-Heino R, Rimpela M, Marttunen M, Rimpela A, Rantanen P. Bullying, depression, and suicidal ideation in Finnish adolescents: school survey. BMJ.1999;319:348–351.

- ^ Menesini E, Eslea M, Smith PK. et al. Cross-national comparison of children's attitudes towards bully/victim problems in school. Aggressive Behav.1997;23:245–257.

- ^ Olweus D. Bullying at School: What We Know and What We Can Do. Oxford, England: Blackwell; 1993.

- ^ O'Moore AM, Smith KM. Bullying behaviour in Irish schools: a nationwide study. Ir J Psychol.1997;18:141–169.

- ^ Whitney I, Smith PK. A survey of the nature and extent of bullying in junior/middle and secondary schools. Educ Res.1993;34:3–25.

- ^ Austin S, Joseph S. Assessment of bully/victim problems in 8 to 11 year-olds. Br J Educ Psychol.1996;66:447–456.

- ^ Forero R, McLellan L, Rissel C, Bauman A. Bullying behaviour and psychosocial health among school students in New South Wales, Australia: cross sectional survey. BMJ.1999;319:344–348.

- ^ Kumpulainen K, Rasanen E, Henttonen I. et al. Bullying and psychiatric symptoms among elementary school-age children. Child Abuse Negl.1998;22:705–717.

- ^ Haynie DL, Nansel TR, Eitel P. et al. Bullies, victims, and bully/victims: distinct groups of youth at-risk. J Early Adolescence.2001;21:29–50.

- ^ Petchesky, R. (2000) 'Sexual rights: inventing a concept, mapping an international practice,' in R. Parker, R.M. Barbosa and P. Aggleton (eds), Framing the sexual subject: The politics of Gender, Sexuality and Power, Berkeley: University of California Press, pp. 81–103

- ^ Bearinger, Linda H., et al. 2007. "Global perspectives on the sexual and reproductive health of adelescents: patterns, prevention, and potential." The Lancet 369.9568: 1226

- ^ Catajan, Maria Elena (March 24, 2014). "NYC: Use SK funds right". SunStar Baguio. Retrieved 26 March 2014.

- ^ a b Furlong, Andy (2013). Youth Studies: An Introduction. USA: Routledge. pp. 227–228. ISBN 978-0-415-56476-2.