Uyghurs: Difference between revisions

Mendsetting (talk | contribs) The photo i replaced suspiciously has adobe photoshop in its metadate instead of data from a personal camera. It was taken from a website and the uploader claimed that he took the photo..... |

Uploader and owner seen to be identical, I see no Problem here. Sometimes uploaders forget to indicate the right place for previously published item. |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{Infobox ethnic group |

{{Infobox ethnic group |

||

|group= Uyghur<br />ئۇيغۇر<br /> |

|group= Uyghur<br />ئۇيغۇر<br /> |

||

|image= [[File: |

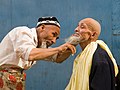

|image= [[File:Uyghur man tomak.jpg|250px]] |

||

|image_caption= Uyghur |

|image_caption= Uyghur man from [[Kashgar]] |

||

|population= |

|population= |

||

|region1={{flagcountry|People's Republic of China}} ([[Xinjiang]]) |

|region1={{flagcountry|People's Republic of China}} ([[Xinjiang]]) |

||

Revision as of 20:03, 4 September 2012

| File:Uyghur man tomak.jpg Uyghur man from Kashgar | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

|---|---|

| 8,399,393 (2000)[1] | |

| 223,100 (2009)[2] | |

| 49,000 (2009)[3] | |

| Languages | |

| Uyghur | |

| Religion | |

| Sunni Islam | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Turkic peoples | |

Template:Contains Chinese text The Uyghurs (Template:Ug; [ʔʊjˈʁʊː][4]; simplified Chinese: 维吾尔; traditional Chinese: 維吾爾; pinyin: Wéiwú'ěr) are a Turkic ethnic group living in Eastern and Central Asia. Today, Uyghurs live primarily in the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region in the People's Republic of China. An estimated 80% of Xinjiang's Uyghurs live in the southwestern portion of the region, the Tarim Basin.[5]

The largest community of Uyghurs outside Xinjiang in China is in Taoyuan County, in south-central Hunan province.[6] Outside of China, significant diasporic communities of Uyghurs exist in the Central Asian countries of Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, and Uzbekistan. Smaller communities are found in Afghanistan, Pakistan, and Turkey.[7]

Name

Uyghur is often pronounced /ˈwiːɡər/ by English speakers, though an acceptable English pronunciation closer to the Uyghur people's pronunciation of it would be /uː.iˈɡʊr/.[8] Several alternate romanizations also appear: Uighur, Uygur, and Uigur. The Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region provincial government recommends that the generic ethnonym [ʊjˈʁʊː], adopted in the early 20th century for this Turkic people,[9] be transcribed as "Uyghur."[10]

The meaning of the term Uyghur is unclear. However, most Uyghur linguists and historians regard the word as coming from uyughur (uyushmaq in modern Uyghur language), literally meaning 'united' or 'people who tend to come together'. Chinese Tang dynasty annals refer to them by the ethnonyms Huí Hú or Huí Hé.[11] The etymology cannot be accurately determined, for historically the groups it denoted were not ethnically fixed, since it denoted a political rather than a tribal identity,[12] or was used originally to refer to just one group among several, the others calling themselves Toquz Oghuz.[13] According to Yin Weixian, the Turkic runic inscriptions record a word uyɣur, which was first transcribed into Chinese as Huí Hé (回紇), but later, in response to an Uyghur request, changed to Huí Hú (回鶻) in 788 or 809. The earliest record of an Uyghur tribe is from the Northern Wei Dynasty (386-534 AD). At that time the ethnonym Gaoche (in Uyghur: Qangqil, قاڭقىل) (Chinese: 高車; pinyin: Gāochē; lit. 'wheelwagon') to the Tura (Chinese: Tiele) tribes. Later, the term Tiele (Chinese: 鐵勒; pinyin: Tiělè; Turkic: Tele) itself was used.[14] The first use of Uyghur as a reference to a political nation occurred during the interim period between the First and Second Göktürk Khaganates (630-684 CE). In modern usage, Uyghur refers to settled Turkic urban dwellers and farmers of Kashgaria or Uyghurstan who follow traditional Central Asian sedentary practices, as distinguished from nomadic Turkic populations in Central Asia. The Bolsheviks reintroduced the term Uyghur to replace the previously used Turk or Turki.[15][16]

Identity

Throughout history, the term Uyghur has taken on an increasingly expansive definition. Initially signifying only a small coalition of Tiele tribes in Northern China, Mongolia, and the Altay Mountains, it later denoted citizenship in the Uyghur Khaganate. Finally it was expanded to an ethnicity, whose ancestry originates with the fall of the Uyghur Khaganate in the year 842 AD, which caused Uyghur migration from Mongolia into the Tarim Basin. This migration assimilated and replaced the Indo-Europeans of the region to create a distinct identity,[17] as the language and culture of the Turkic migrants eventually supplanted the original Indo-European influences. This fluid definition of Uyghur and the diverse ancestry of modern Uyghurs are a source of confusion about what constitutes true Uyghur ethnography and ethnogenesis.

Uyghur activists identify with the Tarim mummies, but research into the genetics of ancient Tarim mummies and their links with modern Uyghurs remain controversial, both to Chinese government officials concerned with ethnic separatism, and to Uyghur activists concerned that research could affect their claims of being indigenous to the region.[18][19] Victor Mair has stated that the Uyghur peoples arrived at the Tarim Basin after the Orkon Uighur Kingdom (present-day Mongolia) fell around 842 AD.[17]

The first use of Uyghur as a reference to a political nation occurred during the interim period between the First and Second Göktürk Khaganates (AD 630-684).[20]

Origin of modern nationality

The term "Uyghur" was not used to refer to any existing ethnic group in the 19th century; the "Uigur" people were referred to in the past tense, as an "ancient" people who no longer existed. For instance, a late 19th-century encyclopedia titled The cyclopædia of India and of eastern and southern Asia said that "Chinese Tartary" (Xinjiang) was at the time "occupied by a mixed population of Turk, Mongol, and Kalmuk".[21] The inhabitants of Xinjiang were not called Uyghur before 1921/1934. Westerners called the Turkic speaking Muslims of the Oases "Turki", and the Turkic Muslims in Ili were known as "Taranchi". The Russians and other foreigners used the names "Sart",[22] "Turk", or "Turki"[23][24] for them. These groups of peoples identified themselves by the oases they came from, not by an ethnic group.[25] Names such as Kashgarliq to mean Kashgari were used.[26] The Turkic people also just used "Musulman", which means "Muslim", to describe themselves.[27][28]

The name "Uyghur" reappeared after the Soviet Union took the ninth-century ethnonym, from the Uyghur Khaganate, and reapplied it to all non-nomadic Turkic Muslims of Xinjiang,[29] following a 19th-century proposal from Russian historians that modern-day Uyghurs were descended from the Turpan Kingdom and Kara-Khanid Khanate, which had formed after the dissolution of the Uyghur Khaganate.[30] Historians generally agree that the adoption of the term "Uyghur" is based on a decision from a 1921 conference in Tashkent, which was attended by Turkic Muslims from the Tarim Basin (Xinjiang).[29][31][32] There, "Uyghur" was chosen by them as the name of their own ethnic group, although the delegates noted that the modern groups referred to a "Uyghur" were distinct from the old Uyghur Khaganate.[33] According to Linda Benson, the Soviets and the Kuomintang intended to foster a Uyghur nationality in order to divide the Muslim population of Xinjiang, whereas the various Turkic Muslim peoples themselves preferred to identify as "Turki", "East Turkestani", or "Muslim".[22] According to Dru Gladney, the modern Uyghur nationality is not directly descended from the old Uyghur Khaganate, in spite of the name.[34]

On the other hand, the ruling regime of China at that time, the Kuomintang, grouped all Muslims, including the Turkic-speaking people of Xinjiang, into the "Hui nationality".[35][36] They generally referred to the Turkic Muslims of Xinjiang as "Chan Tou Hui" (turban-headed Muslim).[22][37][38] Westerners traveling in Xinjiang in the 1930s, like George W. Hunter, Peter Fleming, Ella K. Maillart, and Sven Hedin all referred to the Turkic Muslims of the region not as Uyghur, but as "Turki", in their books. Use of the term "Uyghur" was unknown in Xinjiang until 1934, when the governor Sheng Shicai came to power in Xinjiang. Sheng adopted the Soviets' ethnographic classification rather than the Kuomintang one, and became the first to officially promulgate the use of the term "Uyghur" to describe the Turkic Muslims of Xinjiang.[30][33][39] After the Communist victory, the Chinese Communist Party under Mao Zedong continued the Soviet classification, using the term Uyghur to describe the modern ethnic group.[22]

Another ethnic group, the Buddhist Yugur of Gansu, by contrast, have consistently been called by themselves and others the "Yellow Uyghur" (Säriq Uyghur).[40] Scholars like Joana Breidenbach say that the Yugur's culture, language, and religion are closer to the original culture of the original Uyghur Karakorum state than is the culture of the modern Uyghur people of Xinjiang.[41] Linguist and ethnographer S. Robert Ramsey has argued for inclusion both the Yugur and the Salar as subgroups of Uyghur (based on similar historical roots for the Yugur, and perceived linguistic similarities for the Salar). These groups are recognized as separate ethnic groups, though, by the Chinese government.[42]

In current usage, Uyghur refers to settled Turkic urban dwellers and farmers of the Tarim Basin and Ili who follow traditional Central Asian sedentary practices, as distinguished from nomadic Turkic populations in Central Asia. However, the Chinese government has also designated as "Uyghur" certain peoples with significantly divergent histories and ancestries from the main group. These include the Loplik people and the Dolan people, who are thought to be closer to the Oirat Mongols and the Kyrgyz.[43][44]

Gallery

-

Uyghur Barber in Kashgar. Traditionally Uyghur men shave their heads and wear a hat.

-

Uyghurs at a market, Khotan

-

Young woman at the ruins of Melikawat

-

A young Uyghur girl

-

Uyghur woman at a silk factory, Khotan

-

Young boys at the market

-

Three Uyghur girls at a Sunday market in Khotan

-

Tool sharpeners at the market, Khotan

-

Silk spinning, Khotan

-

Uyghur camel drivers in Xinjiang

-

Uyghur girl from Kashgar

-

Young Uyghur woman, c. 2005

History

Uyghur history can be divided into four distinct phases: Pre-Imperial (300 BC – AD 630), Imperial (AD 630–840), Idiqut (AD 840–1200), and Mongol (AD 1209–1600), with perhaps a fifth modern phase running from the death of the Silk Road in AD 1600 until the present. After the collapse of the Uyghur Khaganate in AD 840, Uyghur resettled from Mongolia to the Tarim Basin, assimilating the Indo-European population, which had previously been driven out of the region by the Xiongnu.[45]

The ancestors of the Uyghur tribe were Turkic pastoralists called Tiele, who lived in the valleys south of Lake Baikal and around the Yenisei River.

The Uyghur Khaganate stretched from the Caspian Sea to Manchuria and lasted from AD 745 to 840.[20] It was administered from the imperial capital Ordu-Baliq, one of the biggest ancient cities built in Mongolia. In AD 840, following a famine and civil war, the Uyghur Khaganate was overrun by the Kirghiz, another Turkic people. As a result the majority of tribal groups formerly under Uyghur control migrated to what is now northwestern China, especially to the modern Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous region.

Following the collapse of the Uyghur Khaganate, the Uyghurs established kingdoms in present day Gansu and Xinjiang.

Yugor, the easternmost state formed by the Yugur people, was the Ganzhou Kingdom (AD 870–1036), with its capital near present-day Zhangye in the Gansu province of China.

Karakhoja, this Uyghur state was the Karakhoja Kingdom (created during AD 856–866 near Turfan), also called the "Idiqut" ("Holy Wealth, Glory") state. The Idiquts (title of the Karakhoja rulers) ruled independently until the 1120s, when they submitted to the Qara Khitai, then continued as vassal rulers under the Mongols from 1209.

Kara-Khanids, or the Karakhans (Black Khans) Dynasty, was a state formed by the a confederation of Karluks, Chigils, Yaghma and other tribes in Semirechye, Western Tian Shan and Kashgaria, and who later conquered Transoxiana. (Note that these were separate Turkic tribes and were not the Uyghurs of the Uyghur Khaganate.)

Both the Idiqut and the Kara-Khanid states eventually submitted to the Kara Khitais. The Uighur Idiqut, Barchukh, voluntarily submitted Genghis Khan (r.1206-1227) and was given his daughter, Altani (ᠠᠯᠲᠠᠨ).[46] From 1260s onwards, they were directly controlled by the Yuan Dynasty of the Great Khagan Kublai (r.1260-1294). However, Mongol princes from Central Asia repeatedly launched raids into Uighurstan to take the control from the Yuan. Most of the Uighurs including the ruling dynasty fled to Gansu (under Yuan Dynasty) due to the conflict between the Mongols.

The Chagatai Khanate was a Mongol ruling khanate controlled by Chagatai Khan, second son of Genghis Khan. Chagatai's ulus, or hereditary territory, consisted of the part of the Mongol Empire which extended from the Ili River (today in eastern Kazakhstan) and Kashgaria (in the western Tarim Basin) to Transoxiana (modern Uzbekistan and Turkmenistan). The exact date that the control of Turfan and other areas of Uighurstan was transferred to another Mongol Dynasty, Chagatai Khanate, is unclear.).[47] Many scholars claim Chagatai Khan (d.1241) inherited Uighurstan from his father, Genghis Khan, as appanage in the early 13th century.[48] By 1330s, the Chagatayids exercised the full authority over the Uighur Kingdom in Turfan.[49]

After the death of the Chagatayid ruler Qazan Khan in 1346, the Chagatai Khanate was divided into western (Transoxiana) and eastern (Moghulistan/Uyghuristan) halves, which was later known as "Kashgar and Uyghurstan," according Balkh historian Makhmud ibn Vali (Sea of Mysteries, 1640). The Chagatayid Mongols of Moghulistan converted to Islam in 1359.

The Qing dynasty conquered Xinjiang in the 18th century.[50]

In Beijing, a community of Uyghurs was clustered around the Mosque near the Forbidden City, having moved to Beijing in the 1700s.[51]

In the Dungan revolt (1862–1877) of 1864, the Uyghurs were successful in expelling the Qing Dynasty officials from parts of southern Xinjiang, and founded an independent Kashgaria kingdom, called Yettishar (English: "country of seven cities"). Under the leadership of Yakub Beg, it included Kashgar, Yarkand, Hotan, Aksu, Kucha, Korla and Turpan. Large Qing Dynasty forces under Chinese General Zuo Zongtang attacked Kashgaria in 1876. After this invasion, the region, which had been known as the Xiyu special administrative area, was reorganized into a province named "Xinjiang", which when literally translated means "New Territory".

In 1912, the Qing Dynasty was replaced by the Republic of China. By 1920, Pan-Turkic Islamists had become a challenge to Chinese warlord Yang Zengxin (杨增新) who controlled Siankiang.

Uyghurs staged several uprisings against Chinese rule. Twice, in 1933 and 1944, the Uyghurs successfully regained their independence(backed by the Soviet Communist leader Joseph Stalin): the First East Turkestan Republic was a short-lived attempt at independence of land around Kashghar, and it was destroyed by Chinese Muslim army under General Ma Zhancang and Ma Fuyuan at the Battle of Kashgar (1934). The Second East Turkistan Republic was a Soviet puppet Communist state which existed from 1944 to 1949 in what is now Ili Kazakh Autonomous Prefecture.

Mao declared the founding of the People's Republic of China on October 1, 1949. He turned the Second East Turkistan Republic into the Ili Kazakh Autonomous Prefecture, and appointed Saifuddin Azizi as the region's first Communist Party governor. Many Republican loyalists fled into exile in Turkey and Western countries. The name Xinjiang was changed to Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region, where they are the largest ethnic group and Uyghurs are mostly concentrated in the southwestern Xinjiang.[52] (see map, right)

The Uyghur identity remains fragmented, as some support a Pan-Islamic vision, exemplified in the East Turkestan Islamic Movement, others support a Pan-Turkic vision, as in the East Turkestan Liberation Organization and a third group would like a "Uyghurstan" state, as in the East Turkestan independence movement. As a result, "No Uyghur or East Turkestan group speaks for all Uyghurs, although it might claim to", and Uyghurs in each of these camps have committed violence against other Uyghurs who they think are too assimilated to Chinese or Russian society or not religious enough.[53] Mindful not to take sides, Uyghur leaders like Rebiya Kadeer mainly try to garner international support for the "rights and interests of the Uyghurs", including the right to demonstrate, although the Chinese government has accused her of orchestrating the deadly July 2009 Ürümqi riots.[54]

Uyghurs of Taoyuan, Hunan

Around 5,000 Uyghurs live around Taoyuan County and other parts of Changde in Hunan province.[55][56][57][58] They are descended from a Uyghur leader, Hala Bashi, from Turpan, sent to Hunan by the Ming Emperor in the 14th century, to crush the Miao rebels during the Miao Rebellions (Ming Dynasty).[6][59] Along with him came Uyghur soldiers from whom the Hunan Uyghurs also descend. The 1982 census records 4,000 Uyghurs in Hunan.[60] They have genealogies which survive 600 years later to the present day. Genealogy keeping is a Han Chinese custom which the Hunan Uyghurs adopted. These Uyghurs were given the surname Jian by the Emperor.[61] There is some confusion as to whether they practice Islam or not. Some say that they have assimilated with the Han and do not practice Islam anymore, and only their genealogies indicate their Uyghur ancestry.[62] Chinese news sources report that they are Muslim.[6]

The Uyghur troops led by Hala were ordered by the Ming Emperor to crush Miao rebellions and were given titles by him. Jian is the predominant surname among the Uyghur in Changde, Hunan. Another group of Uyghur have the surname Sai. Hui and Uyghur have intermarried in the Hunan area.[63] The Hui are descendants of Arabs and Han Chinese who intermarried, and they share the Islamic religion with the Uyghur in Hunan.[63] It is reported that they now number around 10,000 people. The Uyghurs in Changde are not very religious, and eat pork.[63] Older Uygurs disapprove of this, especially elders at the mosques in Changde, and they seek to draw them back to Islamic customs.[63]

In addition to eating pork, the Uyghurs of Changde Hunan practice other Han Chinese customs, like ancestor worship at graves. Some Uyghurs from Xinjiang visit the Hunan Uyghurs out of curiosity or interest.[63] Also, the Uyghurs of Hunan do not speak the Uyghur language, instead, they speak Chinese as their native language, and Arabic for religious reasons at the mosque.[63]

Genetics

The Uyghurs are a population with Eastern and Western Eurasian anthropometric and genetic traits. Uyghurs are thus one of the many populations of Central Eurasia that can be considered to be genetically related to European and East Asian populations. However, various scientific studies differ on the size of each component.[64] One study, using samples from Hetian (Hotan) only, found that Uyghurs have 60% European ancestry and 40% East Asian ancestry.[65] A further study showed slightly lesser European component (52%) in the Uyghur population in southern Xinjiang, but slightly greater East Asian component (53%) in the northern Uyghur population.[66] Another study used a larger sample of individuals from a wider area, and found only about 30% European component to the admixture.[67] A study on mitochondrial DNA (therefore the matrilineal genetic contribution) found the frequency of western Eurasian-specific haplogroup in Uyghurs to be 42.6%.[68]

The admixture may be the result of a continuous gene flow from populations of European and Asian descent, or may be formed by a single event of admixture during a short period of time (the hybrid isolation model). If a hybrid isolation model is assumed, it can be estimated that the hypothetical admixture event occurred about 126 generations ago, or 2520 years ago assuming 20 years per generation.[65][69]

According to the paper by Li et al.

STRUCTURE cannot distinguish recent admixture from a cline of other origin, and these analyses cannot prove admixture in the Uyghurs; however, historical records indicate that the present Uyghurs were formed by admixture between Tocharians from the west and Orkhon Uyghurs (Wugusi-Huihu, according to present Chinese pronunciation) from the east in the 8th century CE. The Uyghur Empire was originally located in Mongolia and conquered the Tocharian tribes in Xinjiang. Tocharians such as Kroran have been shown by archaeological findings to appear phenotypically similar to northern Europeans, whereas the Orkhon Uyghur people were clearly Mongolians. The two groups of people subsequently mixed in Xinjiang to become one population, the present Uyghurs.

— [67]

Culture

Most Uyghurs are Sunni Muslim.[70]

Education

Uyghurs in China, unlike the Salar and Hui who are also mostly Muslim, generally do not oppose coeducation (grouping male and female students together).[71] Conversely, women are generally excluded from public Uyghur Muslim life, also in contrast to Salar and Hui practice.[70]

Literature

Most of the early Uyghur literary works were translations of Buddhist and Manichean religious texts, but there were also narrative, poetic, and epic works apparently original to the Uyghurs.[citation needed] Some of these have been translated into German, English, Russian, and Turkish. Among hundreds of important works surviving from that era are Qutatqu Bilik (Wisdom Of Royal Glory) by Yüsüp Has Hajip (1069–70), Mähmut Qäşqäri's Divan-i Lugat-it Türk- A Dictionary of Turkic Dialects(1072), and Ähmät Yüknäki's Atabetul Hakayik. Perhaps the most famous and best loved pieces of modern Uyghur literature are Abdurehim Otkur's Iz, Oyghanghan Zimin, Zordun Sabir's Anayurt and Ziya Samedi's (former minister of culture in Sinkiang Government in 50's) novels Mayimkhan and Mystery of the years.[citation needed]

Medicine

Chinese Song Dynasty (906–960) sources indicate that an Uyghur physician named Nanto traveled to China and brought with him many kinds of medicine unknown to the Chinese. There were 103 herbs used in Uyghur medicine recorded in a medical compendium by Li Shizhen (1518–1593), a Chinese medical authority. Today, traditional Uyghur medicine can still be found at street stands. Similar to other traditional medicine, diagnosis is usually made through checking the pulse, symptoms, and disease history, and then the pharmacist pounds up different dried herbs, making personalized medicines according to the prescription. Modern Uyghur medical hospitals adopted modern medical science and medicine and adopted evidence-based pharmaceutical technology to traditional medicines.

Art

During the late 19th and early 20th centuries, scientific and archaeological expeditions to the region of Xinjiang's Silk Road discovered numerous cave temples, monastery ruins, and wall paintings, as well as miniatures, books, and documents. There are 77 rock-cut caves at the site. Most have rectangular spaces with rounded arch ceilings often divided into four sections, each with a mural of Buddha. The effect is of an entire ceiling covered with hundreds of Buddha murals. Some ceilings are painted with a large Buddha surrounded by other figures, including Indians, Persians and Europeans. The quality of the murals vary with some being artistically naive while others are masterpieces of religious art.[72]

Music

Muqam is the classical musical style. The 12 Muqams are the national oral epic of the Uyghurs. The muqam system developed among the Uyghur in northwest China and Central Asia over approximately the last 1500 years from the Arabic maqamat modal system that has led to many musical genres among peoples of Eurasia and North Africa. Uyghurs have local muqam systems named after the oasis towns of Xinjiang, such as Dolan, Ili, Kumul and Turpan. The most fully developed at this point is the Western Tarim region's 12 muqams, which are now a large canon of music and songs recorded from the traditional performers Turdi Akhun and Omar Akhun among others in the 1950s and edited into a more systematic system. Although the folk performers probably improvised their songs as in Turkish taksim performances, the present institutional canon is performed as fixed compositions by ensembles.

The Uyghur Muqam of Xinjiang has been designated by UNESCO as part of the Intangible Heritage of Humanity.[73]

Amannisa Khan, sometimes called Amanni Shahan, (1526–1560) is credited with collecting and thereby preserving the Twelve Muqam.[74] Russian scholar Pantusov writes that the Uyghurs manufactured their own musical instruments; they had 62 different kinds of musical instruments and in every Uyghur home there used to be an instrument called a "dutar".

Cuisine

Uyghur food (Uyghur Yemekliri) is characterized by mutton, beef, camel, chicken, goose, carrots, tomatoes, onions, eggplant, celery, various dairy foods, and fruits.

Uyghur-style breakfast is tea with home-baked bread, hardened yogurt, olives, honey, raisins, and almonds. Uyghurs like to treat guests with tea, naan and fruit before the main dishes are ready.

Sangza (Uyghur: ساڭزا) are crispy and tasty fried wheat flour dough twists, a holiday specialty. Samsa (Uyghur: سامسا) are lamb pies baked using a special brick oven. Youtazi is steamed multilayer bread. Göshnan (Uyghur: گۆشنان) are pan-grilled lamb pies. Pamirdin are baked pies with lamb, carrots, and onion inside. Xurpa is lamb soup (Uyghur: شۇرپا). Other dishes include Tohax, a different type of baked bread, and Tunurkawab.

See also

References

This article incorporates text from The cyclopædia of India and of Eastern and Southern Asia: commercial, industrial and scientific, products of the mineral, vegetable, and animal kingdoms, useful arts and manufactures, by Edward Balfour, a publication from 1885, now in the public domain in the United States.

This article incorporates text from The cyclopædia of India and of Eastern and Southern Asia: commercial, industrial and scientific, products of the mineral, vegetable, and animal kingdoms, useful arts and manufactures, by Edward Balfour, a publication from 1885, now in the public domain in the United States.

- ^ Chen, Yangbin (2008). Muslim Uyghur Students in a Chinese Boarding School. Lexington Books. p. 9.

In 1990, the Uyghur population was 7,214,431, the Hui population 8,602978, according to data from the fourth national census. China's Population Statistics Yearbook 1990, www.147.8.31.44/fulltextc/disknj/nj73/10/000012.pdg, viewed on 23 July 2006. In 2000, the Uyghur population was 8,399393, and the Hui population 9,816805, according to data from the fifth national census. Tabulation of the 2000 Population Census of the People's Republic of China. China Statistics Publishing House (2002), 218–221.

- ^ Агентство Республики Казахстан по статистике :Итоги переписи населения Республики Казахстан 2009 года...Численность населения Республики Казахстан по итогам переписи населения 2009 года на момент счета на 12 часов ночи с 24 на 25 февраля 2009г. составила 16004,8 тыс. человек . Доля уйгуров в общей численности населения страны составила – 1,4%.Численность казахов увеличилась по сравнению с предыдущей переписью на 26,1% и составила 10098,6 тыс. человек. Увеличилась численность узбеков на 23,3%, составив 457,2 тыс. человек, уйгур - на 6%, составив 223,1 тыс. человек. Снизилась численность русских на 15,3%, составив 3797,0 тыс. человек; немцев - на 49,6%, составив 178,2 тыс. человек; украинцев – на 39,1%, составив 333,2 тыс. человек; татар – на 18,4%, составив 203,3 тыс. человек; других этносов – на 5,8%, составив 714,2 тыс. человек.

- ^ Национальный статистический комитет Кыргызской Республики : Перепись населения и жилищного фонда Кыргызской Республики 2009 года в цифрах и фактах - Архив Публикаций - КНИГА II (часть I в таблицах) : 3.1. Численность постоянного населения по национальностям

- ^ Mair, Victor (13 July 2009). "A Little Primer of Xinjiang Proper Nouns". Language Log. Retrieved 30 July 2009.

- ^ Dillon, Michael (2004). Xinjiang: China's Muslim far northwest. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-32051-1. p.24

- ^ a b c "Ethnic Uygurs in Hunan Live in Harmony with Han Chinese". People's Daily. 29 December 2000.

- ^ "Ethno-Diplomacy: The Uyghur Hitch in Sino-Turkish Relations" (PDF). Retrieved 2011-08-28.

- ^ Reinhard F. Hahn, Spoken Uyghur, University of Washington Press, 2006, p. 4. Ui or uy is pronounced as in '(b)uoy'. See Michael Robert Drompp, Tang China and the collapse of the Uighur Empire: a documentary history, Brill, 2005, p. 7, n. 1.

- ^ J. Fletcher, "China and Central Asia 1368-1884," in J.K. Fairbank, (ed.) The Chinese World Order, Harvard University Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts, 1968, pp. 206–224, 337–368; p. 364, n. 90. Hakan Özoğlu, Kurdish notables and the Ottoman state: evolving identities, competing loyalties, and shifting boundaries, SUNY press, 2004, p. 16 cites Dru C. Gladney for the view that: "The ethnonym 'Uighur' was most likely suggested to the Chinese nationality affairs officials by Soviet advisors in Xinjiang in 1930."

- ^ The Terminology Normalization Committee for Ethnic Languages of the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region (11 October 2006). "Recommendation for English transcription of the word 'ئۇيغۇر'/《维吾尔》". Retrieved 14 June 2011.

- ^ Colin MacKerras, The Uighur Empire According to the T'ang Dynasty Histories, Australian National University, 1972, p. 224.

- ^ Hakan Özoğlu, p. 16.

- ^ Lilla Russell-Smith, Uygur patronage in Dunhuang: regional art centres on the northern Silk Road in the tenth and eleventh centuries. Brill, 2005, p. 32.

- ^ Hamilton, 1962.

- ^ The term Turk was a generic label used by members of many ethnic groups in Soviet Central Asia. Often the deciding factor for classifying individuals belonging to Turkic nationalities in the Soviet censuses was less what the people called themselves by nationality than what language they claimed as their native tongue. Thus, people who called themselves "Turk" but spoke Uzbek were classified in Soviet censuses as Uzbek by nationality. See Brian D. Silver, "The Ethnic and Language Dimensions in Russian and Soviet Censuses", in Ralph S. Clem, ed., Research Guide to the Russian and Soviet Censuses (Ithaca: Cornell Univ. Press, 1986): 70-97.

- ^ Ramsey, S. Robert (1987). The Languages of China. Princeton: Princeton University Press, pp. 185–6.

- ^ a b "The mystery of China's celtic mummies". The Independent. London. August 28, 2006. Retrieved 2008-06-28.

{{cite news}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ "Genetic testing reveals awkward truth about Xinjiang's famous mummies". Khaleejtimes.com. 2005-04-19. Retrieved 2011-08-28.

- ^ Wong, Edward (2008-11-19). "The Dead Tell a Tale China Doesn't Care to Listen To". The New York Times.

- ^ a b Güzel, Hasan Celal; Oğuz, C. Cem (2002). The Turks. Vol. 2. Ankara: Yeni Türkiye. ISBN 975-6782-55-2. OCLC 49960917.

- ^ Edward Balfour (1885). The cyclopædia of India and of Eastern and Southern Asia: commercial, industrial and scientific, products of the mineral, vegetable, and animal kingdoms, useful arts and manufactures (3 ed.). LONDON: B. Quaritch. p. 952. Retrieved 2010-06-28.(Original from Harvard University)

- ^ a b c d Linda Benson, Ingvar Svanberg (1998). China's last Nomads: the history and culture of China's Kazaks (illustrated ed.). M.E. Sharpe. pp. 20–21. ISBN 1-56324-782-8. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- ^ The term "Turk" was a generic label used by members of many ethnic groups in Soviet Central Asia. Often the deciding factor for classifying individuals belonging to Turkic nationalities in the Soviet censuses was less what the people called themselves by nationality than what language they claimed as their native tongue. Thus, people who called themselves "Turk" but spoke Uzbek were classified in Soviet censuses as Uzbek by nationality. See Brian D. Silver, "The Ethnic and Language Dimensions in Russian and Soviet Censuses", in Ralph S. Clem, Ed., Research Guide to the Russian and Soviet Censuses (Ithaca: Cornell Univ. Press, 1986): 70-97.

- ^ Ildikó Bellér-Hann (2008). Community matters in Xinjiang, 1880-1949: towards a historical anthropology of the Uyghur (illustrated ed.). BRILL. p. 50. ISBN 90-04-16675-0. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- ^ Justin Jon Rudelson (1997). Oasis identities: Uyghur nationalism along China's Silk Road (illustrated ed.). Columbia University Press. ISBN 0-231-10787-0. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- ^ Ho-dong Kim (2004). Holy war in China: the Muslim rebellion and state in Chinese Central Asia, 1864-1877 (illustrated ed.). Stanford University Press. p. 68. ISBN 0-8047-4884-5. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- ^ Ho-dong Kim (2004). Holy war in China: the Muslim rebellion and state in Chinese Central Asia, 1864-1877 (illustrated ed.). Stanford University Press. p. 3. ISBN 0-8047-4884-5. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- ^ Ho-dong Kim (2004). Holy war in China: the Muslim rebellion and state in Chinese Central Asia, 1864-1877 (illustrated ed.). Stanford University Press. p. 3. ISBN 0-8047-4884-5. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- ^ a b Ildikó Bellér-Hann (2007). Situating the Uyghurs between China and Central Asia. Ashgate Publishing, Ltd. p. 32. ISBN 0-7546-7041-4. Retrieved 2010-07-30.

- ^ a b James A. Millward (2007). Eurasian crossroads: a history of Xinjiang. Columbia University Press. p. 208. ISBN 0-231-13924-1. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- ^ Arienne M. Dwyer, East-West Center Washington (2005). The Xinjiang conflict: Uyghur identity, language policy, and political discourse (PDF) (illustrated ed.). East-West Center Washington. p. 75, note 26. ISBN 1-932728-28-7. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- ^ Edward Allworth (1990). The modern Uzbeks: from the fourteenth century to the present : a cultural history (illustrated ed.). Hoover Press. p. 206. ISBN 0-8179-8732-0. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- ^ a b Linda Benson (1990). The Ili Rebellion: the Moslem challenge to Chinese authority in Xinjiang, 1944-1949. M.E. Sharpe. p. 30. ISBN 0-87332-509-5. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- ^ Susan J. Henders (2006). Susan J. Henders (ed.). Democratization and Identity: Regimes and Ethnicity in East and Southeast Asia. Lexington Books. p. 135. ISBN 0-7391-0767-4. Retrieved 2011-09-09.

- ^ Suisheng Zhao (2004). A nation-state by construction: dynamics of modern Chinese nationalism (illustrated ed.). Stanford University Press. p. 171. ISBN 0-8047-5001-7. Retrieved 2011-06-12.

- ^ Murray A. Rubinstein (1994). The Other Taiwan: 1945 to the present. M.E. Sharpe. p. 416. ISBN 1-56324-193-5. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- ^ American Asiatic Association (1940). Asia: journal of the American Asiatic Association, Volume 40. Asia Pub. Co. p. 660. Retrieved 2011-05-08.

- ^ This is in contrast to the Hui people, who were just called "Hui" (Muslim) by the Chinese, and the Salar people, who were called "Sala Hui" (Salar Muslim), by the Chinese. The usage of the term "Chan Tou Hui" was considered a slur and was demeaning. (Garnaut, Anthony. 2008. From Yunnan to Xinjiang:Governor Yang Zengxin and his Dungan Generals. Pacific and Asian History, Australian National University. p. 95)

- ^ Simon Shen (2007). China and antiterrorism. Nova Publishers. p. 92. ISBN 1-60021-344-8. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- ^ Justin Ben-Adam Rudelson, Justin Jon Rudelson (1997). Oasis identities: Uyghur nationalism along China's Silk Road. Columbia University Press. p. 178. ISBN 0-231-10786-2. Retrieved 2010-10-31.

- ^ Joana Breidenbach (2005). China inside out: contemporary Chinese nationalism and transnationalism (illustrated ed.). Central European University Press. p. 275. ISBN 963-7326-14-6. Retrieved 2010-10-31.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|editors=ignored (|editor=suggested) (help) - ^ Ramsey, S. Robert (1987). The Languages of China. Princeton: Princeton University Press. pp. 185–6.

- ^ Gladney, Dru (2004). Dislocating China: Reflections on Muslims, Minorities, and Other Subaltern Subjects. C. Hurst. p. 195.

- ^ Harris, Rachel (2004). Singing the Village: Music, Memory, and Ritual Among the Sibe of Xinjiang. Oxford University Press. pp. 53, 216.

- ^ "A meeting of civilisations: The mystery of China's Celtic mummies". Independent.co.uk. 2006-08-28. Retrieved 2012-04-06.

- ^ Thomas T. Allsen- The Yuan Dynasty and the Uighurs in Turfan in: Ed. Morris Rossabi, China Among Equals: The Middle Kingdom and Its Neighbors, 10th-14th centuries, pp. 246

- ^ Thomas T. Allsen- The Yuan Dynasty and the Uighurs in Turfan in: Ed. Morris Rossabi, China Among Equals: The Middle Kingdom and Its Neighbors, 10th-14th centuries, pp. 258

- ^ Barthold- Four Studies, pp.43-53

- ^ Dai Matsui-A Mongolian Decree from the Chaghataid Khanate Discovered at Dunhuang, p.166

- ^ Map of China

- ^ China monthly review, Volume 8. Millard Publishing Co., inc. 1919. p. 64. Retrieved 2011-05-08.

- ^ 2000年人口普查中国民族人口资料,民族出版社,2003/9 (ISBN 7-105-05425-5)

- ^ Christofferson, Gaye (2002). "Constituting the Uyghur in U.S.-China Relations: The Geopolitics of Identity Formation in the War on Terrorism" (PDF). Strategic Insights. 1 (7). Center for Contemporary Conflict.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Hongmei, Li (2009-07-07). "Unveiled Rebiya Kadeer: a Uighur Dalai Lama". People's Daily. Retrieved 2010-08-21.

- ^ stin Jon Rudelson, Justin Ben-Adam Rudelson (1992). Bones in the sand: the struggle to create Uighur nationalist ideologies in Xinjiang, China. Harvard University. p. 30. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- ^ Ingvar Svanberg (1988). The Altaic-speakers of China: numbers and distribution. Centre for Mult[i]ethnic Research, Uppsala University, Faculty of Arts. p. 7. ISBN 91-86624-20-2. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- ^ Ingvar Svanberg (1988). The Altaic-speakers of China: numbers and distribution. Centre for Mult[i]ethnic Research, Uppsala University, Faculty of Arts. p. 7. ISBN 91-86624-20-2. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- ^ Kathryn M. Coughlin (2006). Muslim cultures today: a reference guide. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 220. ISBN 0-313-32386-0. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- ^ Justin Ben-Adam Rudelson, Justin Jon Rudelson (1997). Oasis identities: Uyghur nationalism along China's Silk Road. Columbia University Press. p. 178. ISBN 0-231-10786-2. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- ^ Zhongguo cai zheng jing ji chu ban she (1988). New China's population. Macmillan. p. 197. ISBN 0-02-905471-0. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- ^ Yangbin Chen (2008). Muslim Uyghur students in a Chinese boarding school: social recapitalization as a response to ethnic integration. Lexington Books. p. 58. ISBN 0-7391-2112-X. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- ^ David Westerlund, Ingvar Svanberg (1999). Islam outside the Arab world. Palgrave Macmillan. p. 197. ISBN 0-312-22691-8. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- ^ a b c d e f Chih-yu Shih, Zhiyu Shi (2002). Negotiating ethnicity in China: citizenship as a response to the state. Psychology Press,. p. 133. ISBN 0-415-28372-8. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) - ^ "Uygur Genetics - DNA of Turkic people from Xinjiang, China". Khazaria.com. Retrieved 2012-04-06.

- ^ a b Shuhua Xu, Wei Huang, Ji Qian, and Li Jin (2008 April 11). "Analysis of Genomic Admixture in Uyghur and Its Implication in Mapping Strategy". Am J Hum Genet. 82 (4): 883–89. doi:10.1016/j.ajhg.2008.01.017. PMC 2427216. PMID 18355773.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Shuhua Xu and Li Jin (September 2008). "A Genome-wide Analysis of Admixture in Uyghurs and a High-Density Admixture Map for Disease-Gene Discovery". Am J Hum Genet. 83 (3): 322–36. doi:10.1016/j.ajhg.2008.08.001. PMC 2556439. PMID 18760393.

- ^ a b Li, H; Cho, K; Kidd, JR; Kidd, KK (2009). "Genetic Landscape of Eurasia and "Admixture" in Uyghurs". American Journal of Human Genetics. 85 (6): 934–7, author reply 937–9. doi:10.1016/j.ajhg.2009.10.024. PMC 2790568. PMID 20004770.

- ^ Yao YG, Kong QP, Wang CY, Zhu CL, Zhang YP. (Dec. 2004). "Different matrilineal contributions to genetic structure of ethnic groups in the silk road region in China". Mol Biol Evol. 21 (12): 2265–80. PMID 15317881.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Uyghurs are hybrids | Gene Expression | Discover Magazine". Blogs.discovermagazine.com. Retrieved 2011-08-28.

- ^ a b Palmer, David; Shive, Glenn; Wickeri, Philip (2011). Chinese Religious Life. Oxford University Press. pp. 61–62.

- ^ Ruth Hayhoe (1996). China's universities, 1895-1995: a century of cultural conflict. Taylor & Francis. p. 202. ISBN 0-8153-1859-6. Retrieved 2010-06-29.

- ^ "Bizaklik Thousand Buddha Caves". www.showcaves.com. Retrieved 2007-09-21.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ "UNESCO Culture Sector - Intangible Heritage - 2003 Convention :". Unesco.org. Retrieved 2011-08-28.

- ^ "Kashgar Welcome You!". Kashi.gov.cn. Retrieved 2011-08-28.

Further reading

- Chinese Cultural Studies: Ethnography of China: Brief Guide at acc6.its.brooklyn.cuny.edu

- Beckwith, Christopher I. (2009). Empires of the Silk Road: A History of Central Eurasia from the Bronze Age to the Present. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-13589-2.

- Findley, Carter Vaughn. 2005. The Turks in World History. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-516770-8, ISBN 0-19-517726-6 (pbk.)

- Güzel, Hasan Celal; Oğuz, C. Cem (2002). The Turks. Vol. 2. Ankara: Yeni Türkiye. ISBN 975-6782-55-2. OCLC 49960917..

- Hessler, Peter. Oracle Bones: A Journey Through Time in China. New York: Harper Perennial, 2006.

- Hierman, Brent. "The Pacification of Xinjiang: Uighur Protest and the Chinese State, 1988-2002." Problems of Post-Communism, May/Jun2007, Vol. 54 Issue 3, pp 48–62

- Human Rights in China: China, Minority Exclusion, Marginalization and Rising Tensions, London, Minority Rights Group International, 2007

- Kaltman, Blaine (2007). Under the Heel of the Dragon: Islam, Racism, Crime, and the Uighur in China. Athens: Ohio University Press. ISBN 978-0-89680-254-4.

- Kamberi, Dolkun. 2005. Uyghurs and Uyghur identity. Sino-Platonic papers, no. 150. Philadelphia, PA: Dept. of East Asian Languages and Civilizations, University of Pennsylvania.

- Mackerras, Colin. Ed. and trans. 1972. The Uighur Empire according to the T'ang Dynastic Histories: a study in Sino-Uyghur relations 744–840. University of South Carolina Press. ISBN 0-87249-279-6

- Millward, James A. and Nabijan Tursun, (2004) "Political History and Strategies of Control, 1884–1978" in Xinjiang: China's Muslim Borderland, ed. S. Frederick Starr. Published by M. E. Sharpe. ISBN 978-0-7656-1318-9.

- Millward, James A. (2007). Eurasian Crossroads: A History of Xinjiang. Columbia University Press, New York. ISBN 978-0-231-13924-3.

- Rall, Ted. Silk Road to Ruin: Is Central Asia the New Middle East? New York: NBM Publishing, 2006.

- Rudelson, Justin Ben-Adam, Oasis identities: Uyghur nationalism along China's Silk Road, New York: Columbia University Press, 1997.

- Tyler, Christian. (2003). Wild West China: The Untold Story of a Frontier Land. John Murray, London. ISBN 0-7195-6341-0.

- Islam in China, Hui and Uyghurs: between modernization and sinicization, the study of the Hui and Uyghurs of China, Jean A. Berlie, White Lotus Press editor, Bangkok, Thailand, published in 2004. ISBN 974-480-062-3, ISBN 978-974-480-062-6.

External links

- Britannica Uighur people

- London Uyghur Ensemble Uyghur Culture and History; multimedia site-links to cultural and historical background, current news, research materials and photographs.

- Uyghur News News aggregator representing the views of Uyghur activists

- Introduction to Uyghur Culture and History Links to cultural and historical background, current news, research materials and photographs.