Larry Eyler

Larry Eyler | |

|---|---|

September 30, 1983 mugshot of Eyler | |

| Born | Larry William Eyler December 21, 1952 Crawfordsville, Indiana, U.S. |

| Died | March 6, 1994 (aged 41) |

| Other names | The Highway Killer The Interstate Killer |

| Height | 6 ft 1 in (185 cm) |

| Parent(s) | George Howard Eyler Shirley Phyllis Kennedy |

| Motive | Rage[1] |

| Conviction(s) | Illinois Murder Aggravated kidnapping Concealment of a homicidal death Indiana Murder[2] |

| Criminal penalty | Illinois Death (October 3, 1986) Indiana 60 years imprisonment (December 28, 1990)[3] |

| Details | |

| Victims | 21+[4] |

Span of crimes | October 23, 1982 – August 19, 1984[5] |

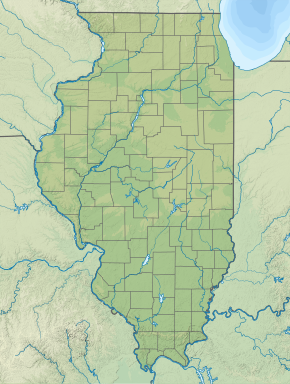

| Country | United States |

| State(s) | Illinois Indiana Kentucky (alleged) Wisconsin (alleged) |

Date apprehended | August 21, 1984 |

| Imprisoned at | Pontiac Correctional Center |

Larry William Eyler (December 21, 1952 – March 6, 1994) was an American serial killer who is believed to have murdered a minimum of twenty-one teenage boys and young men in a series of killings committed in the Midwest between 1982 and 1984.[6] Convicted and sentenced to death by lethal injection for the 1984 kidnapping and murder of 16-year-old Daniel Bridges, he later voluntarily confessed to the 1982 murder of 23-year-old Steven Agan, offering to also confess to his culpability in twenty further unsolved homicides if the state of Illinois would commute his sentence to life imprisonment without parole.[7]

Eyler died of AIDS-related complications in 1994 while incarcerated on death row. Shortly before his death, he confessed to the murders of twenty further young men and boys to his defense attorney Kathleen Zellner, although he denied being physically responsible for the actual murder of Bridges, which he insisted had been committed by an alleged accomplice in five of his homicides, Robert David Little.[8] With her client's consent,[9] Zellner posthumously released Eyler's confession following the formal announcement of his death.[10]

Eyler was known as the Interstate Killer and the Highway Killer due to the fact many of his confirmed and alleged victims were discovered across several midwestern states in locations close to or accessible via the Interstate Highway System.[11]

Early life

[edit]Larry Eyler was born on December 21, 1952, in Crawfordsville, Indiana, the youngest of four children born to George Howard Eyler (September 19, 1924 – September 25, 1971) and Shirley Phyllis (née Kennedy, later DeKoff; April 22, 1928 – June 8, 2016).[12] His father was an alcoholic who is known to have physically and emotionally abused his wife and children. Eyler's parents divorced in mid-1955, and he and his sister were regularly placed in the care of babysitters, foster families, or simply left in the care of their two older siblings (the oldest of whom was aged ten) as their mother struggled to financially support and provide adequate care for four children, working two jobs as a waitress and in a factory on weekdays, and occasionally in a bar at weekends. Nonetheless, when Eyler and his sister were in the care of foster families, their mother would frequently visit her two youngest children, and Eyler would claim these separations and reunions brought the family closer.[7]

In 1957, Eyler's mother remarried. This marriage lasted one year before the couple divorced. His mother married for a third time in 1960, although the couple divorced four years later. She married for the fourth time in 1972. Eyler's father and his first two stepfathers drank heavily, and he and his siblings were subjected to frequent abuse, with one of his stepfathers frequently holding Eyler's head beneath scalding water as a form of discipline.[13]

Eyler attended St. Joseph School in Lebanon, Indiana. Although tall for his age and active in sporting activities, he was regularly targeted by bullies due to his being from a poor family and his parents' divorce, frequently leading to his sister, Theresa, confronting her brother's tormentors. Eyler was viewed by teachers as a quiet yet likable pupil, with few friends.[14] Due to his increasing stubbornness and erratic behavior, Eyler's mother placed him in a home for unruly boys in 1963. He found this experience emotionally devastating, and within weeks had tearfully persuaded his mother to allow him to return home. Shortly thereafter, Eyler underwent psychological tests which revealed him to be of average intelligence, although suffering from severe insecurity and holding an extreme fear of separation and abandonment.[13] Deducing these fears sourced from his home life, staff recommended Eyler be temporarily placed in a Catholic boys' home in Fort Wayne. He remained at this residence for six months before he returned to the care of his mother.[15]

Adolescence and early adulthood

[edit]When he reached puberty, Eyler discovered he was homosexual. He was open about his sexuality only to his family, although he struggled with deep-seated feelings of self-hatred regarding his sexual orientation.[16] Throughout high school, he occasionally dated girls, although none of these relationships became physical.[17] Having been somewhat religious since childhood, Eyler did confide to some close acquaintances how he struggled to accept his sexuality.[18]

In part due to his lackadaisical attitude towards schooling, Eyler failed to graduate from high school, although he did later obtain a General Educational Development certificate.[13] Shortly after leaving college, Eyler obtained employment as a private security guard in the Marion County General Hospital. He worked in this employment for six months before losing this position and finding alternate work within a shoe store. While in this employment, Eyler began familiarizing himself with Indianapolis's gay community, frequenting gay bars and frequently engaging in casual liaisons with men.[17] Several of these individuals noted Eyler averted his eyes from his partner during intercourse while shouting profanities such as bitch and whore, leading many to believe Eyler was fantasizing his partner was female.[19]

Paraphilia

[edit]By the mid-1970s, Eyler was well known within the gay community of Indianapolis—particularly among those with a leather fetish.[15] Several acquaintances within this community described him as a good-looking, "laid-back guy" and avid bodybuilder who was close to his mother and sister, although others who had engaged in sexual activity with him described him as an individual with a sadistic streak and violent temper which would only surface within their sexual encounters,[20] often involving Eyler extensively bludgeoning, then inflicting light knife wounds upon unwilling partners—particularly to their torsos.[19]

Eyler primarily worked as a house painter,[21] and although never having served in the military, he was fond of wearing Marine Corps T-shirts. He resided in a condominium in Terre Haute with a 38-year-old library science professor named Robert David Little, whom he had first met in 1974 while studying at the Indiana State University.[22] The relationship between the two men was a platonic one, with Eyler viewing Little as something of a father figure.[23]

Eyler and Little regularly socialized within Indianapolis's gay community, although Little—a socially awkward, taciturn and unattractive individual—typically struggled to form friendships or obtain sexual partners during these excursions, resulting in Eyler frequently bringing young men to Little's home to engage in sex with the two.[24]

First attempted murder

[edit]On August 3, 1978, Eyler picked up a 19-year-old hitchhiker named Craig Long on 7th Street in Terre Haute.[25] Shortly after Long entered the pickup truck, Eyler propositioned the youth, resulting in Long attempting to leave the vehicle. In response, Eyler pressed a knife against the youth's chest as Long stated, "I don't have any money." Eyler then drove towards a rural field, stating: "It's not your money I want. I'm not after your money." He then ordered Long to undress before he handcuffed the youth, bound his ankles, then ordered him to climb into the back of the pickup. When Long attempted to flee from the pickup as Eyler undressed, Eyler chased after him as Long shouted: "You queer!"[26] In response, Eyler stabbed the youth once in the chest, penetrating his lung. Long slumped to the ground, feigning death. He later stumbled to a nearby house, where the occupants summoned paramedics.[15]

Shortly thereafter, Eyler drove to the house as Long received first aid and offered the handcuff key to a sheriff's deputy, claiming he had stabbed the young man accidentally. He was arrested and taken into custody. A search of his vehicle recovered a hunting knife, a metal-tipped whip, a butcher knife, a further set of handcuffs, tear gas, and a sword.[27]

"His urges got to him. He wasn't realizing what he was doing. He was fantasizing. He learned on that case not to let them be alive anymore, because then ... they can't come back. He learned to kill them."

Journalist and author Gera-Lind Kolarik, reflecting on Eyler's abduction and stabbing of Craig Long (2015)[28]

Eyler was later charged with aggravated battery, to which he agreed to plead guilty. A judge set his bond at $10,000, a sum which was raised by friends. He was released on bail until August 23. On this date, Eyler's lawyers offered Long a check from Little for $2,500 in return for his agreeing not to press charges. Long accepted the offer, and Eyler changed his plea to not guilty. As such, he was acquitted on November 13, being fined $43 in court costs.[29]

Long-term relationship

[edit]In August 1981, Eyler formed a long-term relationship with a 20-year-old married man named John Dobrovolskis. Dobrovolskis lived with his wife, two children, and three foster children on North Greenview Avenue in Chicago, Illinois. His wife, Sally, was tolerant of her husband's sexual orientation and of the fact her husband's lover often lodged with them on weekdays, paying a third of the rent.[30]

Both Eyler and Dobrovolskis held a penchant for sadomasochism, and their sexual activity frequently involved Eyler binding his partner to devices before proceeding to beat and lash him as he hurled curses at Dobrovolskis before the two engaged in penetrative sex.[31] Although neither Eyler nor Dobrovolskis was inclined towards monogamy, the couple considered their relationship a permanent one. Nonetheless, Eyler constantly sought assurance he was the only man in his lover's life, and the two are known to have frequently argued over Eyler's accusations of his lover's infidelity. These arguments would occasionally lead to Dobrovolskis striking Eyler, who never retaliated in these physical altercations. Occasionally, the couple's arguments were initiated by the perceptions and recriminations of Robert Little, who made no secret of his intense dislike of Dobrovolskis to Eyler and resented the fact he was in a long-term relationship.[32]

Although Eyler primarily, and intermittently, worked as a house painter in Illinois on weekdays, he also worked as a liquor store clerk in Greencastle, Indiana on Saturdays. As such, he regularly traveled between the two states, living rent free at Little's Terre Haute residence at weekends.[33]

Murders

[edit]Between 1982 and 1984, Eyler is known to have committed a minimum of twenty-one murders and one attempted murder. All his murders involved the restraining of his victim, and several victims were subjected to varying degrees of sadomasochism before being stabbed and/or slashed to death, with the majority of the wounds being inflicted to the victim's chest and abdomen.[35] His victims were typically plied with alcohol and sedatives such as ethchlorvynol before their restraint and murder. Several victims were disemboweled after death, and Eyler is known to have dismembered the bodies of four of his victims. His victims were typically discarded in fields close to major Interstate highways with their trousers and underwear frequently discovered around their knees or ankles and their shirts and wallets missing from the crime scene.[36][7]

On October 12, 1982, Eyler lured a 21-year-old named Craig Townsend into his vehicle in Crown Point, Indiana. Although drugged, extensively beaten and later abandoned naked and comatose in a rural field (causing Townsend to also suffer from exposure), the young man survived this assault.[37] Eleven days later, on October 23, Eyler abducted and murdered a 19-year-old named Steven Crockett.[38][39] His body was discovered in a cornfield in Kankakee County approximately twelve hours after his murder. An autopsy revealed Crockett had been beaten, then stabbed to death, suffering thirty-two knife wounds, including four to his head.[7] One week later, on October 30, a 26-year-old named Edgar Underkofler disappeared from Rantoul, Illinois. His body was not discovered until March 4, 1983, in a field close to Danville, Illinois.[40] Sometime the following month, Eyler murdered a 25-year-old barman named John Johnson. His body was discovered one month later in Lowell, Indiana.[41] On November 20, Eyler abducted a 19-year-old hitchhiker named William Lewis at a location close to Vincennes, Indiana. He was stabbed to death and buried in a field close to Rensselaer, Indiana.[42][43]

On December 19, a 23-year-old named Steven Agan was abducted in Terre Haute. His body was discovered in woodland close to Indiana State Road 63 on December 28. An examination of the outbuilding of an abandoned farm close to the crime scene revealed several traces of human flesh upon the walls in areas where plaster had been damaged, leading investigators to speculate Agan had been suspended against the walls of this property as his murderer had inflicted the injuries to his body.[44] Noting the extensive mutilation upon Agan's abdomen, chest, and throat, the coroner who performed this autopsy, Dr. John Pless, referenced the "tremendous rage" Agan's killer had exhibited upon his victim in his autopsy report, adding a likelihood of there being more than one perpetrator in this murder.

Immediately after concluding Agan's autopsy, Pless conducted the autopsy upon the body of a 21-year-old named John Roach, whose body had been found close to Interstate 70 in Putnam County that day. Pless noted striking similarities in the injuries inflicted upon Roach and Agan; again noting multiple stab wounds to the victim's abdomen, upper chest and throat, suggesting an overt rage exhibited by the perpetrator.[45]

On December 30, a 22-year-old Yale University graduate named David Block disappeared from the Illinois suburb of Highland Park, having told his family of his intentions to visit a friend in the nearby city of Highwood.[46] His body was discovered by a farmer in a field south of Illinois Route 173 on May 7, 1984.[47]

1983

[edit]On January 24, 1983, Eyler abducted and murdered a 16-year-old named Ervin Gibson in Lake County, Illinois. His body was not discovered until April 15, discarded atop the body of a dog which had also been stabbed to death.[48] Between March and April 1983, Eyler is believed to have killed a minimum of five further victims between the ages of 17 and 29. On May 9, the body of 21-year-old Daniel Scott McNeive was discovered in a field close to Indiana State Road 39 in Hendricks County. The wounds inflicted to McNeive immediately tied his murder to other victims tentatively linked to the same perpetrator. He had suffered eleven knife wounds to his neck, five to his back, and eleven to his abdomen, with one wound causing sections of his small intestine to protrude through his abdomen. Furthermore, welt marks were discovered on McNeive's wrists and ankles, and his jeans had been pulled down to his ankles. As with other victims, McNeive's body bore no signs of his being subjected to a sexual assault.[49] Nine days later, Eyler murdered a 25-year-old named Richard Bruce in Effingham, Illinois. His body was thrown from a bridge into a creek, and remained undiscovered until December 5.[50]

Many advocates within Indiana's gay community had speculated the sudden increase in the number of disappearances and murders of young males might be the work of a single perpetrator by early 1983. Although police had routinely raided gay bars and bookstores in addition to continually overtly filming patrons of these premises in their efforts to identify the movements of suspects, that month the gay newspaper The Works, in their own efforts to assist police, created an anonymous telephone hotline and published an article speculating as to both the identity and motive of the perpetrator, whom they speculated struggled to accept his sexuality. With assistance from members of the gay community and the family of one murder victim, the editors of the newspaper offered a reward of $1,500 for any information obtained leading to the arrest and conviction of the killer.[51]

By the early spring of 1983, police in Indiana had tentatively linked several murders of young males committed in the state to the same perpetrator.[52] Six days after the discovery of McNeive's body, the Indiana State Police conducted a meeting attended by thirty-five detectives from each of the four jurisdictions where bodies of young males bearing wounds suggesting the same perpetrator had been discovered. The conclusion of this meeting was that the same individual had murdered in each jurisdiction, and that all involved in the investigation should form a unified task force dedicated to the apprehension of the suspect. The four separate murder investigations within Indiana were amalgamated into one, with investigators agreeing that this task force would comprise two detectives from the state police, two from the Indianapolis police, and two from each county involved in the manhunt. This task force—named the Central Indiana Multi-Agency Investigation Team (CIMAIT)—was commanded by Lieutenant Jerry Campbell of the Indianapolis police. All information obtained was entered into a computerized database linked to the statewide police system.[53]

Coordinated task force

[edit]On the first day of CIMAIT's existence, the task force contacted the FBI's National Crime Information Center, describing the method of murder and body disposal of the offender they were seeking and requesting police forces who had discovered young male murder victims whose wounds matched this pattern to contact them. Shortly thereafter, investigators in Kentucky contacted the task force reporting that a 29-year-old Lexington resident named Jay Reynolds had been discovered stabbed to death in Madison County on March 22, and that his body had likely been transported to the site of its discovery.[54] Days later, investigators in Chicago reported that the body of an 18-year-old African-American teenager named Jimmie Roberts had been found with thirty-five stab wounds to his body in Thorn Creek on May 9.[37] Both victims were linked to the manhunt for the same perpetrator, whom this task force termed the Highway Murderer.[55]

On June 6, a former lover of Eyler's named Thomas Henderson phoned the investigation team's confidential hotline to voice his suspicions that Eyler might be the killer they were seeking; he explained that his former lover had been charged with "some sort of stabbing" of a young hitchhiker in 1978, possessed a violent temper, and had a penchant for bondage. Henderson added that Eyler worked in a liquor store in Greencastle on Saturdays and lived in Terre Haute with an older male on the weekends. He also informed investigators that in May 1982,[56] Eyler had drugged a 14-year-old boy, later abandoning the unconscious teenager in woodland close to Greencastle. The boy had not been molested, and investigators theorized the reason Eyler had given the boy sedatives was as a means to test the effectiveness of the drug.[57]

Conducting a background check on Eyler, investigators discovered he had been arrested in 1978 for attempting to sexually assault a teenage hitchhiker whom he had stabbed and left for dead. The handcuffing of the youth's wrists and binding of his ankles matched the modus operandi of the Highway Murderer, whose victims had also been discovered with welt marks upon their wrists and ankles. Furthermore, Eyler was known to regularly travel between Indianapolis and Chicago.[58] This information was considered sufficient to keep an informal track of Eyler's whereabouts, but not to place him under full surveillance.[59][n 1]

FBI profile

[edit]At the request of CIMAIT, the FBI developed a psychological profile of the unknown killer, whom they predicted to be a white male in his late twenties or early thirties who worked in a menial profession and who presented a rough exterior in part due to his self-hatred regarding his sexual attraction to other males.[61]

The individual would project a "macho" image and seek the company and approval of other masculine males in order to feel a sense of belonging;[61] as such, this individual would frequent "redneck bars" and be something of a night owl, yet live on the edge of homosexual panic; always fearful of being labeled by others as "queer". Due to this fear, this offender may express a hatred of homosexuals in order to mask his sexual attraction to those from whom he sought acceptance.[62] Furthermore, the FBI predicted that upon completion of a murder, the offender would symbolically erase the act by making a rudimentary effort to cover his victim with leaves or soil,[7] and that this individual likely had a middle-aged, middle-class, and markedly more intelligent accomplice in several of his initial homicides.[13][63]

As many victims had been athletic and lithe in stature, this profile also predicted the offender to be a physically strong individual. The predictions within this profile regarding the offender's strength were supported by the presence of deep welt marks upon the wrists of many victims, suggesting they had struggled to resist being bound and handcuffed.[64]

Further murders

[edit]On July 2, the partially-clad body of an unidentified Hispanic man was discovered in a field two miles from the city of Paxton in Ford County, Illinois.[65] This victim had been dead since June 27 or 28, and had been repeatedly stabbed in the abdomen.[66] Eight weeks later, on August 31, a tree-trimming crew discovered the body of a further victim, a 28-year-old named Ralph Calise, in a field close to a tollway near Illinois Route 60. He had been stabbed seventeen times with a butcher or hunting knife, with several wounds inflicted to his abdomen causing sections of his small intestine to protrude through his body.[67] Lake County investigators quickly linked this murder to the stabbing deaths of two other young men whose bodies had been discovered close to this decedent earlier in 1983 (Ervin Gibson and Gustavo Herrera).[68]

In early September, a Chicago-based reporter for WLS-TV named Gera-Lind Kolarik noted similarities between the August 31 murder of Calise and the two earlier deaths of young males within Lake County.[7] Kolarik was familiar with other murders of young males committed in Indiana, bearing similar signature knife mutilations, and speculated that the perpetrator of these earlier Indiana murders had begun to murder and/or dispose of his victims' bodies in Lake County.[69] Conversing with Cook County investigators, Kolarik discovered that a further two young male murder victims who had lived in or disappeared from Uptown in 1982 had also been discovered with multiple stab wounds to their bodies and their trousers and underwear pulled down to their ankles in Kankakee County, Illinois, and Lowell, Indiana.[70][n 2]

On September 8, investigators from all jurisdictions in both states where these additional bodies had been discovered convened with the senior task force representatives in Crown Point to discuss whether these additional five deaths were also linked to the same perpetrator.[72] All five murders were added to the list of victims compiled by the task force, whom investigators now believed to have murdered up to seventeen young males.[73][n 3]

One month later, on October 4, two mushroom hunters discovered a human torso concealed inside a plastic bag in Kenosha County, Wisconsin.[74] The victim was identified on October 11 as 18-year-old Eric Hansen, a St. Francis teenager who had last been seen alive on September 27 in Downtown Milwaukee.[75] Hansen's head, arms, and legs had been severed from his torso with a hacksaw, and the torso itself had been completely drained of blood. The skull and hands were never found.[76][77]

On October 18 and 19, the partially-decomposed bodies of four further victims were discovered alongside an oak tree close to an abandoned farmhouse in Lake Village, Indiana.[28] Each victim had been dead for several months, and all four decedents had been partially buried, with sections of the body of each victim remaining exposed above ground, suggesting the murderer had made only rudimentary efforts to bury each victim. Three of these victims—all Caucasian—were buried at one side of the tree, three feet apart, with their heads facing north. A fourth victim—an African-American teenager—was buried at the other side of the tree.[78] All four victims had been stabbed more than two dozen times with a blade at least eight inches in length, and the trousers of each victim were discovered around their ankles.[79][n 4]

Two months later, on December 7, a hunter discovered the partially-buried skeleton of a further victim in Hendricks County, close to U.S. Route 40. The victim was identified as 17-year-old Richard Wayne, who had disappeared on March 20 while traveling from California to his home in Montpelier, Indiana.[81] The body of a second, less-decomposed victim was discovered beneath the remnants of a burned mobile home a few feet from where Wayne had been buried. This decedent was determined to be an African-American, approximately 5 feet 9 inches (1.75 m) in height, although his remains were never identified.[82]

First arrest

[edit]On September 30, Eyler was arrested in Lowell, Indiana for a routine traffic violation. He had been in the company of a young hitchhiker at the time of his apprehension and both men were arrested and detained for questioning at a Lowell state police post, with Eyler initially being detained upon charges of soliciting a young male for sexual purposes after a sergeant named William Cothran—without Eyler's consent and before informing him he was under arrest—had searched his Ford F-Series pickup at the roadside and discovered two sections of nylon rope. His vehicle was impounded.[83][n 5]

Shortly after 1:30 p.m., two investigators from CIMAIT conducted a formal interview with Eyler, whom they informed had become a suspect in the series of murders due to an anonymous phone call received from a former acquaintance of his. Although willing to discuss any other aspect of his life and their suspicions of his having committed murder, Eyler refused to discuss his sexuality. Questioned about the murders of John Roach and Daniel McNeive, Eyler claimed to have read press coverage of both murders in the Indianapolis Star, but he denied ever having committed murder. He consented to the investigators' request to conduct a forensic examination of his vehicle and also agreed to allow investigators to take his mug shot, copies of his fingerprints, and to subject him to a polygraph test at a later date.[85]

Evidence retrieval

[edit]A search of Eyler's vehicle recovered a knife,[86] two sections of nylon rope, handcuffs, a hammer, two baseball bats, a mallet, and surgical tape.[15] An inspection of Eyler's footwear and vehicle revealed the impressions of his boots to be a precise match to plaster casts taken of imprints discovered alongside the body of Ralph Calise. The pattern of his vehicle's tire tracks was also deemed similar. Moreover, blood was discovered beneath the handle of the knife found inside his vehicle, and he was known to have regularly commuted between three districts in Indiana and Illinois where several victims' bodies had been discovered: Greencastle, Terre Haute, and Chicago.[11][n 6] In addition, Eyler's lifestyle closely matched that predicted upon the psychological profile of the murderer earlier compiled by the FBI.[7][n 7]

Upon completion of the forensic examination of Eyler's pickup, Indiana investigators informed Eyler he was free to leave custody and retain possession of his vehicle. Due to concerns regarding Eyler's knowledge that he was now a murder suspect might lead to his disposing of any potential evidence, in the early hours of October 1, investigators from CIMAIT obtained a search warrant authorizing their search of the Terre Haute home of Robert Little. This search was conducted at dawn on October 2 and revealed further circumstantial evidence, such as credit card receipts, indicating Eyler's presence in jurisdictions within both Illinois and Indiana on dates identified victims linked to the Highway Murderer had been killed. An examination of phone bills retrieved from the property revealed Eyler had regularly placed collect calls to Little's home at odd hours, shortly after identified victims were believed to have been murdered. One of these calls to Little's home had been placed from a payphone near the Cook County Hospital on April 8—the murder date of victim Gustavo Herrera. Hospitalization records revealed Eyler had received treatment for a deep cut to his hand on this date, which he claimed had been caused in a fall from his truck in which he had landed upon a glass beer bottle;[87] receipts recovered from the property revealed he had purchased handcuffs and a knife the following day.[88] Investigators further discovered Eyler and Little had recently spent several weeks on vacation in New York City, returning to Indiana shortly before Calise's murder.[89] These revelations led a member of the Indiana task force named Cathy Berner to remark to her colleagues that if Eyler were not the murderer they were seeking, he was following the actual killer on a daily basis.[90]

As the tire impressions obtained by Indiana authorities were not suitable for comparison with the impressions obtained at the site of Calise's murder, Illinois investigators received approval from a state attorney to seize possession of Eyler's truck. The vehicle was impounded at the Lake County sheriff's headquarters on the evening of October 2,[n 8] and Eyler accompanied investigators to Waukegan to submit to further questioning by an investigator named Dan Colin. On this occasion, he admitted to Colin his penchant for being the dominant partner in bondage sessions, that his relationship with Dobrovolskis had been something of a love–hate relationship,[91] that he and Dobrovolskis had frequently argued, and that his lover had occasionally struck him. He denied the tire tracks and boot impressions recovered at the Calise murder scene belonged to him, adding that he had never met the victim. Colin then stated to Eyler: "Larry, we know something about you. You'd get into a fight with John and pick someone else and stab him because you think it's John." This accusation caused Eyler to visibly wince.[92]

Legal representation

[edit]Shortly after his release from custody on October 4, Eyler requested legal representation from a Chicago lawyer named Kenneth Ditkowsky. Having received confirmation from the Lake County Deputy Chief Investigator that police had insufficient evidence to formally charge his client with murder, Ditkowsky filed a civil suit against both the Lake County sheriff's police and the Indiana State Police on October 11, citing the harassment of his client and contending investigators in both states had violated the Fourteenth Amendment and Eyler's civil rights by involving him in their collective investigation with insufficient evidence to formally charge him with murder. This suit sought $250,000 in damages against eleven named officers in both states.[93]

Evidentiary analysis

[edit]On October 6, the boot and tire imprints recovered at the scene of Ralph Calise's murder were sent to the headquarters of the FBI in Washington, D.C. for further analysis and comparison with all physical evidence recovered by Indiana investigators in the task force's efforts to forensically link Eyler to this particular murder. Several days later, the FBI reported to investigators that the boot impressions were a precise match, including four distinctive areas of wearing and damage to the soles. Extensive bloodstains—determined to be type A-positive—were also discovered inside this footwear. Furthermore, the tires on Eyler's vehicle were from two separate manufacturers, and the physical impressions recovered at the murder scene were determined to be from these two separate manufacturers. The tire impressions themselves were a perfect match in terms of grip depth.[94]

On October 27, investigators from CIMAIT and Lake County held a meeting to determine whether sufficient evidence existed to charge Eyler with murder. The outcome of this meeting convinced officers from the two jurisdictions that sufficient evidence existed to charge Eyler with the murder of Ralph Calise.[42] The following day, investigators obtained a warrant permitting their retrieval of Eyler's hair and blood samples for further comparison with evidence earlier retrieved from Eyler's vehicle, to be served the following day—the date of the hearing of Ditkowsky's civil suit.[95]

Ditkowsky's civil suit was heard at the Dirksen Federal Building on October 29, with Ditkowsky requesting permission to access the affidavit investigators had used to request a search warrant for Eyler's vehicle. Although Ditkowsky argued before Judge Paul Plunkett that "not a scintilla of evidence" existed against his client, Judge Plunkett—having reviewed the investigators' collective affidavit—ruled Ditkowsky could not obtain access to the documents at the present date. As Eyler walked from this hearing, two Lake County investigators presented Ditkowsky with warrants authorizing their retrieval of Eyler's blood and hair samples. A sample of Eyler's blood revealed his blood type to be O-positive.[96]

Formal murder charge

[edit]Eyler was formally charged with Calise's murder on October 29, with his bond being set at $1 million,[97] and an initial trial date set for December 19.[98] He protested his innocence, adding in anonymous media interviews that the accusation had harmed his reputation among his family and friends, and proclaiming that, had he murdered any individual, real evidence would have existed.[99][100]

On November 1, Lake County investigators obtained a search warrant to conduct a second search of Robert Little's home. The primary purpose of this search warrant was to determine whether the victims' missing T-shirts and wallets had been retained as keepsakes. Although investigators retrieved 221 items of clothing, jewelry, pharmaceuticals, and Polaroid photographs, none of the items recovered depicted or belonged to any of the murder victims; however, a key recovered in this search was a precise match to a key found beneath the body of Steven Agan. This key was later determined to fit the door of an office where Eyler had worked in 1982.[101]

With the approval of his mother, as well as Little and Dobrovolskis, a criminal defense attorney named David Schippers was appointed to replace Kenneth Ditkowsky as Eyler's legal representative on November 12.[102] Schippers opted to reverse the defense strategy adopted by his predecessor, also forbidding his client to grant any further interviews to the media.[103]

Legality issues

[edit]Following a lengthy evidentiary hearing in December 1983, Lake County Circuit Judge William Block ruled that although Eyler's initial arrest for the traffic violation had been legally valid, his subsequent detainment during which evidence was recovered by Indiana police and now presented before him had been obtained without probable cause,[104] and that Eyler's detention had been illegal.[105] A further hearing to determine whether defense motions to suppress the physical and circumstantial evidence retrieved by investigators between September 30 and November 22 and to quash and nullify various warrants authorizing these searches and the seizure of property was scheduled for January 23, 1984.[106]

Release from custody

[edit]At the subsequent January 1984 hearing to determine whether the physical evidence recovered following Eyler's arrest should be suppressed, a police sergeant named John Pavlakovic conceded the primary reason Lowell police had prolonged Eyler's detainment on September 30 was to await the arrival in Lowell of members of the task force assembled to investigate the series of murders, and that Eyler had never formally been under arrest in relation to any offense other than soliciting a male for sexual purposes. Further testimony pertaining to the Lake County and Chicago officers' search of the Dobrovolski residence on October 3 revealed this search had been conducted without a search warrant.[107]

"The Indiana task force and we were able, working together, to trace Larry's movements for an entire year. There are twenty-one murders that we know of. Through receipts and bills and what have you, we were able to place him at nine of the scenes ... here is the date Steve Crockett disappeared; here is when he was found, and here is where Larry bought gas nearby. Over here is a collect call from the gym where Larry and John Bartlett worked out. Here is when Bartlett disappeared, and here is a gas receipt from practically where Bartlett was found ... don't you see the pattern? He kills, and he makes a call. It's his pattern. Now that you got him off, you better hope there aren't any more long-distance calls to Terre Haute."

Lake County investigator Dan Colin, conversing with Eyler's attorney, David Schippers, following Judge Block's ruling to suppress much of the evidence against his client. February 1, 1984[108]

Following four days of testimony, Judge Block adjourned the hearing until January 27 to consider his ruling, informing the Assistant State's Attorney and David Schippers that sufficient precedents existed for both admitting and suppressing the evidence.[109]

On February 1, Judge Block ruled that although Eyler had signed a Miranda waiver upon being detained, he had been taken into custody for interrogation upon charges unrelated to the crime of murder and was only later detained on charges of soliciting. Citing the exclusionary rule as the basis for his decision, Judge Block ruled the physical evidence recovered by Illinois investigators in their comparison of his boot prints and tire tracks to the plaster casts recovered at the Calise crime scene had been tainted as the search had been prompted by Eyler's initial illegal detainment by Indiana investigators, in violation of his constitutional rights.[99] Furthermore, although Illinois investigators had obtained possession of Eyler's boots from their Indiana counterparts through a subpoena, the boots had never been formally seized by Indiana authorities.[110] Block further ruled the facts detailed in the police affidavit to search Robert Little's home were insufficient to obtain a search warrant. With the exception of the tire impressions and hair and blood samples obtained from Eyler, Block ordered all evidence obtained to be suppressed.[111] Block also reduced Eyler's bond sum to $10,000 on this date.[7]

As a result of this ruling, Eyler was freed from custody on February 6, 1984, his family and Robert Little having paid the reduced bond fee.[7] Terms imposed upon Eyler's bond stipulated he was unable to leave Illinois.[112] In attempts to appeal this ruling, prosecutors submitted several legal challenges, including an appeal against the suppression of this evidence to the Supreme Court of the United States. These appeals were unsuccessful.[99]

Four weeks after his release from custody, Eyler permanently relocated to Chicago. He resided in an apartment complex in Rogers Park, with Robert Little purchasing the furniture within the property, paying the weekly rent,[113] and purchasing a new set of tires for his pickup.[114] At his lawyers' request, Eyler refused to provide John Dobrovolskis with his new address, although his lover soon discovered where Eyler lived.[115]

Murder of Daniel Bridges

[edit]At approximately 10:30 p.m. on August 19, 1984, Eyler lured a 16-year-old Uptown youth named Daniel Bridges to his apartment. The youngest of thirteen children, Bridges was a neglected child and habitual runaway who, although heterosexual,[116] had been a male prostitute since the age of twelve.[105] Bridges had been a close acquaintance of victim Ervin Gibson, and is known to have been wary of Eyler, whom he had described to an NBC reporter (commissioned to film a documentary focusing on child exploitation in America two months before his murder) as a "real freak" who was well known to the male prostitutes of Uptown.[13][117]

Inside Eyler's apartment, the youth was bound to a chair with clothesline before he was beaten, tortured, then stabbed to death. Eyler then dismembered Bridges' body in his bathroom. His body was cut into eight pieces; each of which was completely drained of blood before being placed inside six separate plastic bags.[97]

The dismembered body of Daniel Bridges was discovered by a janitor named Joseph Balla on the morning of August 21, 1984.[118] His remains had been placed inside a garbage dumpster close to Eyler's apartment and within a unit not intended for usage by tenants within Eyler's apartment complex.[13] Believing the bags to have been illegally dumped, Balla chose to remove the bags from the garbage receptacle to inspect the contents. Removing the first bag from the disposal unit caused the bag to split open and reveal the contents to be a severed human leg.[97]

Second arrest

[edit]Reporting his discovery to police, Balla stated that other janitors had observed a tenant named Larry Eyler placing the bags in the dumpster the previous afternoon.[119] Recognizing Eyler's name, a police captain named Francis Nolan informed the four other officers present: "Detain anyone occupying [apartment] 106. I don't care who it is."[120] Within minutes, Eyler was arrested within his apartment. Dobrovolskis was also taken into custody, although he was soon released without charge.[119]

A forensic examination of Eyler's apartment conducted on August 21 and 22 revealed copious quantities of blood had recently been cleaned from his bedroom, which had recently been repainted, although extensive traces of blood spattering were located across the floor, walls, and ceiling.[121] Numerous traces of blood later determined to belong to Daniel Bridges were also discovered upon a mattress, the seat of a chair, a leather belt, a sofa within this room, and beneath the floorboards of the doorway to the bathroom.[28]

Inside Eyler's closet, investigators discovered the decedent's jeans, saturated with rivulets of bloodstains. Bridges' distinctive Duke University T-shirt—also extensively bloodstained—was discovered in a hamper, along with a leather vest belonging to Eyler that had recently been washed.[119] Moreover, investigators discovered a hacksaw on the property. Blades for this tool, plus an awl, were also recovered from a drawer within the utility room.[122] Receipts recovered from the property revealed Eyler had recently purchased several hacksaw blades.[28]

The forensic examination of the bags used to conceal Bridges' remains revealed several fingerprints determined to belong to Eyler.[123] These fingerprints were discovered on both the internal and external surfaces of the bags.[119] On August 24, investigators conducted a luminol test inside Eyler's now empty apartment. This test revealed extensive traces of blood in the bedroom. Further markings across the floors indicated Bridges' body had been dragged from the bedroom into the bathtub, where the teenager's body had evidently been dismembered.[119]

Second murder charge

[edit]On August 22, Eyler was formally charged with Bridges' murder.[124] He denied any knowledge of the crime, insisting his fingerprints must have been inadvertently placed upon the bags containing Bridges' body as he had moved them aside as he had placed other garbage bags within the dumpster.[123]

The same day, Cook County medical examiner Dr. Robert Stein conducted the autopsy upon Bridges' body. This autopsy determined death had been caused due to multiple wounds inflicted via a knife and an awl-like instrument. No facial fractures were evident, although the teenager had evidently been beaten around the right eye, also suffering numerous shallow cuts to his face before his death. Fourteen wounds likely inflicted with an ice pick or an awl were also evident upon and around Bridges' sternum; these wounds had also been inflicted prior to death. Moreover, five knife wounds to the abdomen were markedly deep and had caused sections of Bridges' intestine to protrude through the wounds. Three additional knife wounds to the teenager's back had been inflicted with such force the heart and left lung had been perforated.[125]

In order to legally seek the death penalty, the prosecutors at Eyler's upcoming trial, Mark Rakoczy and Rick Stock, opted to charge Eyler with the felonies of aggravated kidnapping, unlawful restraint, and concealment of Bridges' body, in addition to the charge of murder.[126][n 9]

Trial

[edit]Eyler was brought to trial for the aggravated kidnapping, unlawful restraint, murder, and concealment of the body of Daniel Bridges on July 1, 1986. He was tried in Cook County, Illinois, before Judge Joseph Urso, and chose to enter a formal plea of not guilty to the charges against him.[127] As Eyler was financially insolvent, he was defended by two public defenders named Claire Hilliard and Tom Allen, with David Schippers also informing Judge Urso of his intention to offer his legal services pro bono. Eyler's attorneys instructed their client not to testify on his own behalf.[128]

In his opening statement to the jury on this date, Rakoczy outlined the physical and circumstantial evidence to be presented against the defendant, stating how close Eyler had been to eluding justice in this murder; had janitor Balla not suspected Eyler of simply illegally dumping trash, Bridges' body "would be buried in some landfill". Rakoczy also referenced a remark Eyler had made to a janitor who had asked him what he was disposing into the garbage receptacle as he had placed the bags into the disposal unit: "Just getting rid of some shit from my apartment."[99]

David Schippers delivered the opening statement on behalf of the defense, arguing the sole evidence proving Eyler's involvement in the murder was that he had handled the bags containing Bridges' body, with eyewitnesses also having observed him disposing of the bags in the garbage receptacle, but that no witnesses could prove he had actually murdered the victim. Schippers asserted that two other men had alternately been within Eyler's apartment between August 19 and 21, one of whom had spent a great deal of time there. Furthermore, in relation to the charge of aggravated kidnapping, Schippers stated no evidence existed attesting to Bridges having entered Eyler's apartment involuntarily, adding that there was no evidence he had even been inside Eyler's pickup truck, as a detailed forensic examination of the vehicle had yielded no fibers or fingerprints of the decedent.[129]

Witness testimony

[edit]The first prosecution witness to testify against Eyler was Robert Little, who testified to having been in Eyler's company between 17 and 19 August, although he claimed to have returned to Terre Haute at approximately 10:15 p.m. on the evening of Bridges' murder.[13]

Dr. Robert Stein testified on behalf of the prosecution on July 2. Stein described the extensive torture and mutilation inflicted upon Bridges before and after his death as being "one of the worst cases" he had ever seen, adding the pattern and depth of the serrations discovered upon the decedent's body precisely matched the hacksaw blades recovered from Eyler's apartment. Upon cross-examination, Stein admitted to Tom Allen he had discovered traces of alcohol and cocaine in the victim's blood, suggesting a possibility he had not been kidnapped and had willingly entered Eyler's apartment.[130]

On July 4, a janitor named Al Burdicki testified to having witnessed Eyler make between eight and twelve trips to his communal storage locker on August 20, with Eyler explaining to him he was "getting tools for a job". Several hours later, Burdicki had also witnessed Eyler making three separate trips to the garbage receptacle.[131]

On July 7, John Dobrovolskis testified on behalf of the prosecution, stating he had telephoned Eyler on three occasions between 8:45 p.m. and 11:25 p.m. on the date of Bridges' disappearance, and again at 2:45 a.m. on August 20, only to be informed not to visit his apartment as Eyler was still in the company of Robert Little. Dobrovolskis stated this had been extremely unusual, as Little had typically returned to Terre Haute early on Sundays.[119] Dobrovolskis further testified that in his final phone call, he had informed Eyler of his intentions to be at his apartment in fifteen minutes, only for Eyler to state: "No, don't do that." Eyler had then agreed to travel immediately to Dobrovolskis's home, and upon his arrival, Dobrovolskis noted he had evidently recently bathed or showered. He was disinterested in engaging in sex, at which point Dobrovolskis believed Eyler had been with another man.[132]

Little later confirmed sections of Dobrovolskis's testimony, although he insisted he had left Eyler's apartment approximately fifteen minutes before Bridges is known to have last been seen alive.[119] To support his assertion that he had left Eyler's apartment late on August 19, Little's attorney introduced into evidence a tax receipt proving Little had paid property taxes on his Terre Haute condominium at noon on August 20. When questioned as to why he had paid the bill on this date despite the fact this tax bill was not due until October, Little claimed he had opted to do so as he had the sufficient finances and had simply "decided to pay off some bills".[13]

In efforts by the defense to cast a reasonable doubt in the minds of the jury as to who had committed Bridges' murder, Schippers succeeded in getting Dobrovolskis to concede that the reason Eyler had been "disinterested" in sex may have been that he had engaged in sexual activity with a consenting lover at his apartment, and that this could have been the reason Eyler had actively dissuaded him from visiting his apartment on August 19 and 20.[133] Schippers also referenced the convenience in Little traveling from Rogers Park to Terre Haute to pay a tax bill not due for another two months on the morning after Bridges' murder, also adding that it was odd he had chosen to pay the bill in person, when he habitually paid his bills by mail. Schippers suggested the reason Little had paid this bill in person was an effort to construct an alibi.[131]

Supporting the prosecution's contention Eyler had lured Bridges to his home not to engage in sexual relations but simply to torture and murder the youth a forensic technician named Marion Caporusso testified on July 8 that no semen was found upon or within the victim's body. Upon cross-examination, Caporusso conceded some bloodstains found upon fingernails retrieved from an ashtray in Eyler's apartment did not belong to either Eyler or the decedent, and that no other individual known to have been present in Eyler's apartment between August 19 and 21 had had samples of his blood taken for comparison with these bloodstains.[134]

Closing arguments

[edit]Both prosecution and defense attorneys delivered their closing arguments before the jury on July 9. Deputy Prosecutor Rick Stock delivered the state's closing argument on behalf of the prosecution, outlining the injuries Bridges had received before his death, referencing the premeditated nature of the murder and Eyler's efforts to conceal all evidence of the crime.[135]

Following Stock's closing argument, David Schippers began his own presentation before the jury, promising to "talk sense" regarding the case and the felony charges against his client, before stating: "Where is the evidence Danny Bridges was kidnapped by anyone?" Referencing the welt marks upon the decedent's wrists and ankles, Schippers speculated that as Eyler held a penchant for bondage, Bridges may have willingly submitted to this act. Speculating Eyler may not have been the actual murderer, Schippers hearkened to Dobrovolskis's testimony regarding Robert Little being at Eyler's apartment as late as 2:45 a.m. on August 20 and the convenience in his choosing to pay a tax bill not due for two months later that day in a possible effort to build himself an alibi. Schippers then referenced the state's acceptance of Little's version of events and a lack of any investigation into his potential culpability, adding: "Well, if Little says it, it must be true."[13]

Mark Rakoczy delivered a brief rebuttal argument in which he argued the evidence presented overwhelmingly attested to Eyler's guilt before the state rested its case. Judge Urso then informed the jury of the factors to consider in reaching their deliberations, adding they should allow neither prejudice or sympathy to influence their verdicts. The jurors then retired to consider their verdict.[136]

Conviction

[edit]The jury deliberated for three hours before returning their verdict. Eyler was found guilty of the aggravated kidnapping, unlawful restraint and murder of Daniel Bridges, in addition to the concealment of the teenager's body.[128] His face displayed little emotion as the verdict was announced,[137] although his hands clenched the legs of the attorneys sitting either side of him.[138]

Penalty phase

[edit]On September 30, both prosecution and defense attorneys outlined their arguments in relation to the sentence to be imposed upon Eyler before Judge Urso; these arguments concluded the following day.[139] Prosecutor Richard Stock introduced four individuals who each testified to instances in which they had been assaulted and, in one case, left for dead by Eyler between 1978 and 1981. Outlining the similarities in Eyler's restraining or immobilizing these individuals to the restraint and torture Bridges had endured before he was "finally put out of his misery", Stock added: "There is nothing, Your Honor, that can mitigate the tears and the agony that Larry Eyler has caused in his entire life, thirty-three years, and he has caused more tears than anyone [...] a sentence other than death will be giving him his freedom."[140]

On October 1, David Schippers introduced four character witnesses (Eyler's mother, stepfather, sister, and a Catholic chaplain) to testify to the kindness and decency they had observed in Eyler's character, with Eyler's mother, Shirley DeKoff, referencing her son's emotionally difficult childhood and her frequently marrying and divorcing a succession of abusive husbands as she constantly sought stability for her children. Both Eyler's mother and sister wept as they pleaded with Judge Urso to spare Eyler's life.[141]

Schippers outlined his belief the death penalty should be inappropriate by stating the evidence presented before the jury asserting his client had committed murder was based upon circumstantial evidence. He also referenced historical cases where witnesses had provided false testimony and cases where juries had incorrectly returned guilty verdicts against innocent defendants. Schippers closed his argument before Judge Urso by emphasizing the existence of mitigating factors[13] regarding Eyler's culpability in the actual act of homicide before requesting his client's sentence be life imprisonment.[142]

Death penalty

[edit]Upon hearing the counsels' closing arguments, Judge Urso announced he would return his decision at 10:00 a.m. on October 3.[118] On this date, Judge Urso formally sentenced Eyler to death by lethal injection.[143] Emphasizing his decision had been difficult for him to reach due to his religious beliefs, Urso explained: "The senseless and barbaric murder of a 16-year-old boy, a killing which was so brutal it defies description, shows me your complete disregard for human life. If there ever was a person or a situation for which the death penalty is appropriate, it is you. You are an evil person. You truly deserve to die for your acts. I thereby sentence you to death for the murder of Danny Bridges, committed during the course of his aggravated kidnapping."[13][144]

Following his sentencing, Eyler was transferred to the Pontiac Correctional Center, where he remained incarcerated on death row.[111] Within this facility, Eyler underwent several psychiatric evaluations. These tests concluded Eyler suffered from a severe borderline personality disorder. Noting Eyler's pathological sensitivity to feelings of abandonment, experts theorized Eyler had killed in response to real or perceived feelings of rejection from his lover, discharging his rage upon his victims. Furthermore, these experts believed he had also murdered in order to maintain a sense of control.[145]

Appeal

[edit]In May 1988, Eyler filed a formal appeal against his conviction, contending that although he had dismembered Bridges' body and disposed of the remains, the actual murder itself had been committed by Robert Little in his absence, and this contention had not been rebutted by the prosecution at his trial.[146] This appeal further contended Bridges had been driven to Eyler's apartment by Robert Little (whose vehicle had not been subjected to a forensic examination), and that his alibi had never been corroborated.[113]

This appeal was heard on May 10, 1989, and later dismissed on October 25.[119] An initial execution date was set for March 14, 1990.[147]

On November 5, 1990, an attorney named Kathleen Zellner was appointed by the Illinois Appellate Defender's office to represent Eyler in his ongoing appeals against his conviction.[13]

Further murder conviction

[edit]In November 1990, a Vermillion County prosecutor named Larry Thomas obtained the physical evidence retrieved against Eyler in relation to the murder of Ralph Calise (previously ordered suppressed by Judge William Block) with the intention of presenting the evidence before an Indiana grand jury to determine whether sufficient evidence existed to charge Eyler with the December 1982 murder of Steven Agan.[148]

Upon being informed of his impending indictment in Agan's murder, Eyler agreed to voluntarily confess to his culpability, although he insisted this particular murder had been committed with the assistance of Robert Little.[149] He agreed to confess to his guilt and testify against his alleged accomplice on the condition he be given a fixed term of imprisonment as opposed to a further death sentence. His offer was accepted, and Eyler provided his attorney with a seventeen-page confession on December 4.[150][n 10]

On December 13, Eyler pleaded guilty to the murder of Steven Agan before Judge Don Darnell, additionally testifying Robert Little had been a knowing and willing participant in this murder.[151] (An independent polygraph test conducted prior to Little's trial indicated the authenticity of this assertion, and to Eyler's further claim that Little had been the individual who had actually murdered Daniel Bridges.[13])

Eyler received a sentence of 60 years' imprisonment on December 28, to be served concurrently with his existing sentence.[152] Little (aged 53) was arrested on December 18 and formally charged with Agan's first-degree murder, facing a sentence of 60 years' imprisonment if convicted.[153]

The following month, Kathleen Zellner offered a deal on behalf of her client whereby Eyler would confess to his culpability in twenty further homicides committed across ten counties in Illinois and Indiana if the state of Illinois would commute his death sentence to one of life imprisonment without parole. According to Zellner, her client had offered until the end of January for this deal to be accepted or he would "take his secrets to the grave".[9] Although authorities in eight of these ten jurisdictions readily agreed to offer Eyler a lengthy prison sentence in exchange for his confession, and a ninth jurisdiction indicated a potential willingness but awaited the official response from Cook County, the Cook County State's Attorney, Jack O'Malley, ultimately rejected Eyler's offer.[15][154]

Trial of Robert Little

[edit]Eyler's testimony

[edit]Robert Little was brought to trial on April 11, 1991. He was tried in Vermillion County before Judge Don Darnell,[155] and entered a formal plea of not guilty on this date.[156]

Eyler testified against his alleged accomplice at this trial, claiming he and Little had both committed the murder of Agan on December 19, 1982. According to Eyler, the two had regularly socialized within Indianapolis's gay community, occasionally bringing young men to Little's home to engage in sex, with Little frequently photographing the sexual acts.[157]

Testimony from Eyler asserted that on the date of the murder, Little had suggested the two "do a scene", which he had understood to mean commit a murder for sexual pleasure as Little photographed the event with a Polaroid camera.[158][n 11] He and Little had lured Agan—whom Eyler had vaguely known through frequenting the car wash where Agan had worked[159]—into Little's vehicle in Terre Haute, initially with the promise of Agan simply drinking with the two. Although Agan was heterosexual,[160] he agreed to participate in a bondage and photography session for money.[161]

The two men had initially driven Agan to a location close to the Terre Haute Regional Airport, where a guardsman ordered the three off airport grounds.[n 12] Eyler then drove toward an abandoned shed close to Indiana State Road 63. At this location, Agan's hands were tied above a beam before he was gagged and bound. According to Eyler, Little then shouted, "Get out the knife" before he had proceeded to stab Agan. Eyler further testified Little had repeatedly masturbated while photographing him as he had bound and repeatedly stabbed Agan,[157] and that Little had also stabbed the young man before stating to Eyler, "Okay, kill the motherfucker."[13] Little had taken Agan's undershirt from the crime scene, and had later complained to Eyler the overall murder ritual had been too fast for his liking.[163]

Cross-examination

[edit]Upon cross-examination, one of Little's defense attorneys, Dennis Zahn, asserted that because Little had appeared as a witness for the prosecution at Eyler's earlier trial for the murder of Daniel Bridges, he was simply implicating Little in a further murder he had committed as a form of revenge. In support of this contention, Zahn questioned Eyler in regard to fifteen other alleged victims of his; on each occasion, Eyler exercised his Fifth Amendment rights and suggested Little's attorneys could ask their client about those homicides.[164] When questioned as to whether he had dismembered the body of Daniel Bridges, Eyler admitted that he had committed this act, although he denied responsibility for the teenager's actual murder.[13]

Further questioned as to why no photographs had been found depicting Agan's restraint and murder in police searches of Little's home in either 1983 or 1990, Eyler stated Little had disposed of the photographs following the 1983 search of his home, adding the pictures had been inside a closet in Little's bedroom, which had not been searched.[165]

On April 12, Dr. John Pless recounted the autopsy he had performed upon Agan's body on December 28, 1982. Dr. Pless testified as to having viewed several eviscerated bodies in his career, before stating: "This is the [most extensively mutilated body] I've seen without the body being cut into pieces." Pless testified that many of the beating, stabbing, and slashing injuries had been inflicted after Agan was already deceased, although numerous deep wounds to the neck and groin had been inflicted while the young man was still alive. He further testified that he could not conclusively pinpoint the actual time of Agan's death, but stated his belief the young man had been killed prior to December 21.[163]

Defense attorney James Voyles claimed his client had not been in Indiana in the week before Christmas on any year between 1958 and 1989. To support this contention, Little's mother testified she had relocated from Indiana to Florida in 1958; that her son had first visited her home approximately a week before Christmas that year; and that he had "never missed a Christmas" at her home on any year since.[166] Furthermore, he had invariably stayed at her home until New Year's Day.[13] However, this claim had earlier been discredited by prosecutor Mark Greenwell, who had introduced into evidence ledger records proving Little's vehicle had been brought to a Terre Haute garage for minor repair work on December 21, 1982, and a phone bill proving a call had been made from Little's home on the same day before the prosecutors had rested their case on April 15.[167]

Although Little had been prepared to testify in his own defense, his attorneys advised him not to do so on April 16; explaining their belief his mother's testimony had made an impression on the jurors' minds and that if he testified, his sexuality would largely be on trial.[168]

Closing arguments

[edit]Both prosecution and defense attorneys delivered their closing arguments before the jury on April 17. Mark Greenwell described the murder as being "a performance" orchestrated at Little's instruction, adding that the murder had been committed to satisfy the defendant's lust for sadomasochistic bondage. Greenwell also inferred Eyler had nothing to personally gain by asserting Little had actively participated in this murder, adding Eyler had readily admitted to physically taking the decedent's life.[169]

Dennis Zahn described his client as an individual victimized because of his sexuality and portrayed Eyler as a convicted murderer cynically fabricating accusations against his client in a "last ditch" effort to have his death sentence commuted. Referencing the twenty-four occasions in which Eyler had exercised his Fifth Amendment rights in response to questioning by the defense, Zahn ended his closing argument by asking the jurors: "Would you convict an honorable man on the word of Larry Eyler?"[170]

Acquittal

[edit]After deliberating for over seven hours, the jury found Little not guilty of all charges on April 17. Little grinned as the verdict was read before hugging his attorney as Steven Agan's brother and parents ran out of the courtroom. Following his acquittal, Little held a press conference in which he informed reporters: "I'm just so happy the ordeal is over", before stating his intentions to return to his teaching position at the Indiana State University.[167]

Death

[edit]Larry Eyler died in the infirmary of the Pontiac Correctional Center on March 6, 1994.[171] His death was due to AIDS-related complications; he had been seriously ill for approximately ten days prior to his death.[121]

At the time of Eyler's death, his attorney, Kathleen Zellner, had prepared a further appeal disputing her client's conviction in the Bridges murder. This appeal was pending in the Illinois Supreme Court, and Zellner remained confident Eyler's conviction would have been overturned.[13]

The appeal itself maintained that one of Eyler's defense attorneys, David Schippers, had a conflict of interest as he had received a payment of $16,875 from Robert Little to assist in Eyler's defense at his trial for the murder of Daniel Bridges, although Little had appeared as a witness for the prosecution. Schippers had informed Judge Urso he was offering his legal services free of charge; adding he would inform the court if these circumstances changed.[172] As such, the appeal contended Schippers had been guilty of attorney misconduct and that Eyler's conviction had therefore been unsafe.[13] Zellner maintained her conviction that a conflict of interest of this magnitude would undoubtedly have resulted in Eyler securing a retrial.[173] This appeal further claimed that Little had been the individual who had actually murdered Daniel Bridges.[174]

Shortly after her client's death, Zellner confirmed that she would proceed with filing the appeal to clarify various outstanding legal issues pertaining to a lack of police investigation into Robert Little as a potential culprit in Bridges' abduction and murder and regarding documents negating her client's aggravated kidnapping conviction, which had not been made available to Eyler's defense attorneys either prior to or after his trial.[174]

Posthumous confession

[edit]Two days after Eyler's death, Kathleen Zellner called a press conference in which she revealed the names and/or descriptions of seventeen individuals whom her client confessed to having personally murdered, and naming four other individuals—Steven Crockett, Steven Agan, an unidentified Caucasian murdered in late-May 1983,[175][n 13] and a further unidentified Caucasian male murdered in April 1984[178]—whom Eyler claimed had been murdered with the assistance of Robert Little (to whom Zellner referred in this press conference as "an unnamed individual still living in Indiana").[179] Zellner emphasized her client's insistence Little had been the individual who had actually murdered Daniel Bridges.[8]

According to Zellner, her client had been an emotionally insecure individual who had viewed Robert Little as something of the father figure he had never had in his life, and this had left Eyler vulnerable to manipulation, with Little using him as a means of facilitating his own access to young males for sexual purposes in return for the financial support he provided. Zellner further asserted Eyler's paraphilia had inadvertently increased his penchant for violence and that Little had begun to encourage her client to project his extreme self-hatred regarding his homosexuality and the conflict between his sexual preference and his religious beliefs onto other males approximately six months before the two had abducted and murdered Steven Crockett.[180] Furthermore, Eyler had been actively encouraged, aided and abetted in all his subsequent murders by Little,[113] who had known of all of his crimes.[181]

Emphasizing her belief in Eyler's confessions, Zellner elaborated that her client had been formally diagnosed with AIDS in March 1991 and therefore "knew when he testified at [Little's] trial in the Steven Agan murder that he was dying. I believe Larry was truthful. Larry had no incentive to lie to anyone."[113]

In his posthumous confession, Eyler stated he had typically lured his victims—who included both heterosexuals and homosexuals[182]—with promises of drugs, alcohol, money, or transport[183][184] and that, immediately prior to stabbing several of his victims, he had pressed the blade of his knife against their abdomen before informing his victim to "make peace with God".[151][185] Furthermore, Eyler claimed he had never engaged in sex with any of his victims,[186] and he had frequently given his victims' T-shirts to Robert Little to use in masturbatory fantasies.[181]

Zellner stated Eyler had begun compiling a list of his victims shortly after she had been appointed as his legal representative in November 1990 in an effort to obtain a plea bargain whereby his sentence would be commuted to one of life imprisonment. With his health in gradual decline, Eyler had authorized his attorney to publicly release his confessions after his death, with his explanation being that the families of his victims would know he had confessed to the murders of their relatives.[187][10]

"I think the only right thing he ever did with his life was giving me permission to come here today ... the reason I'm here is so that the families know, he did confess to the murders of your sons. He told me that, and I hope that can bring you some peace of mind."

Attorney Kathleen Zellner, addressing family members of Eyler's victims. March 8, 1994[188][189]

Victims

[edit]Eyler's posthumous confession revealed he had murdered twenty-one teenage boys and young men between 1982 and 1984, being assisted by his alleged accomplice Robert Little in four of these murders.[37] He denied any culpability in the physical murder of Daniel Bridges, although he admitted to the dismemberment and disposal of the teenager's body.[8] Investigators strongly believe Eyler is also responsible for two further homicides committed in Wisconsin and Kentucky in 1983.[178]

In his formal confession, Eyler claimed to have committed his murders in part as a means of relieving internal frustrations frequently triggered by fights with his lover,[190] and to his achieving a sense of relief after the act.[191] His victims were hitchhikers,[192] male prostitutes, or individuals he had generally encountered by happenstance.[193] Each victim would be plied with alcohol and sedatives and driven to a remote area where Eyler would typically wait for an opportune moment to handcuff his victim.[194] He would then overpower, gag, blindfold, and bind his victim hand and foot before proceeding to bludgeon and lash his victim before murdering him.[195]

Of these twenty further victims to which Eyler posthumously confessed, ten had been committed in Indiana, and ten in Illinois. Furthermore, according to Eyler, the body of one of these victims—an Uptown male prostitute known as "Cowboy" killed in his Rogers Park apartment in April 1984—had never been found.[196][n 14]

In April 2021, one of the four victims discovered alongside an oak tree close to an abandoned farmhouse in Lake Village, Indiana on October 18 and 19, 1983 was positively identified using DNA and genetic genealogy as John Brandenburg Jr. of Chicago.[197] A further victim, discovered in Jasper County, Indiana on October 15, 1983, was identified in December 2021 as William Lewis of Peru, Indiana,[198][199] and a further victim discovered at the abandoned farmhouse in Lake Village was identified in July 2023 via forensic genealogy as Keith Bibbs.[200]

Summary

[edit]| Name | Age | Date of murder | Date of discovery | Location of murder |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Steven Malcolm Crockett[201] | 19 | October 23, 1982 | October 23, 1982 | Kankakee County, Illinois |

| Edgar Anthony Underkofler[40] | 26 | October 30, 1982 | March 4, 1983 | Vermilion County, Illinois |

| John R. Johnson[41] | 25 | November 1982 | December 25, 1982 | Lake County, Indiana |

| William Joseph Lewis[198] | 19 | November 20, 1982 | October 15, 1983 | Jasper County, Indiana |

| Steven Ray Agan[202] | 23 | December 19, 1982 | December 28, 1982 | Vermillion County, Indiana |

| John Lee Roach[45] | 21 | December 22, 1982 | December 28, 1982 | Putnam County, Indiana |

| David M. Block[160] | 22 | December 30, 1982 | May 7, 1984 | Lake County, Illinois |

| Ervin Dwayne Gibson[203] | 16 | January 24, 1983 | April 15, 1983 | Lake County, Illinois |

| John Daniel Bartlett[204][205] | 19 | March 2, 1983 | October 18, 1983 | Newton County, Indiana |

| Michael Christopher Bauer[193] | 22 | March 8, 1983 | October 18, 1983 | Newton County, Indiana |

| Richard Arthur Wayne Jr.[206] | 17 | March 20, 1983 | December 7, 1983 | Hendricks County, Indiana |

| Jay Trulon Reynolds*[54] | 29 | March 22, 1983 | March 22, 1983 | Madison County, Kentucky |

| Gustavo Pineda Herrera[207] | 26 | April 8, 1983 | April 8, 1983 | Lake County, Illinois |

| Jimmie T. Roberts[208] | 18 | May 4, 1983 | May 9, 1983 | Cook County, Illinois |

| Daniel Scott McNeive[209] | 21 | May 7, 1983 | May 9, 1983 | Hendricks County, Indiana |

| Richard Edward Bruce Jr.[192] | 25 | May 18, 1983 | December 5, 1983 | Effingham County, Illinois |

| John Ingram Brandenburg Jr.[210][211] | 19 | c. May 29, 1983 | October 19, 1983 | Newton County, Indiana |

| Keith Lavell Bibbs[212] | 16 | c. July 11, 1983 | October 18, 1983 | Newton County, Indiana |

| Ralph Ervin Calise[7] | 28 | August 31, 1983 | August 31, 1983 | Lake County, Illinois |

| Eric R. Hansen*[213] | 18 | September 27, 1983 | October 4, 1983 | Kenosha County, Wisconsin |

| Daniel H. Bridges[214] | 16 | August 19, 1984 | August 21, 1984 | Cook County, Illinois |

Footnote

- Although Eyler did not confess to the murders of Jay Reynolds and Eric Hansen, he is considered a strong suspect in both homicides.[215]

Unidentified victims

[edit]Three of Eyler's victims still remain unidentified,[216] the body of one of whom has never been found. The body of one of these unidentified decedents was discovered in Indiana, with one further victim discovered in Illinois. Each unidentified decedent is listed below in order of body discovery,[6] with the final entry being an entry within Eyler's posthumous confession to one further murder he claimed to have committed with the assistance of Robert Little in 1984.[175][195]

|

Aftermath

[edit]Following Eyler's arrest and conviction for the murder of Daniel Bridges, Lake County Circuit Judge William Block suffered political repercussions as a result of his decision to suppress evidence pertaining to Eyler's guilt in the murder of Ralph Calise and to reduce his bond sum to $10,000. Block later unsuccessfully bid to be appointed to the Illinois Appellate Court. He remained a circuit court judge in Waukegan.[219]

Eyler's lover, John Dobrovolskis, relocated to California shortly after his arrest. He later returned to live with his wife, Sally, in Chicago. Dobrovolskis died of AIDS in January 1990 at the age of 29.[220]

Shortly after his 1991 acquittal of the murder of Steven Agan, Robert Little returned to the teaching position he had held at the Indiana State University since 1971, and continued to maintain his lack of knowledge of and innocence in any murders Eyler had committed.[153]

On the day Eyler's posthumous confession was revealed by his attorney, a spokesman for the Cook County State's Attorney stated to the media that despite Eyler's claims to have been assisted by Little in four murders,[221] and that Little had actually murdered Daniel Bridges, insufficient real evidence existed to substantiate Eyler's admissions and that no further investigation into Little's alleged participation in Eyler's murders would ensue.[188]