Musaid bin Abdul Rahman Al Saud

| Musaid bin Abdul Rahman Al Saud | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||

| Minister of Finance | |||||

| In office | 15 March 1962 – 14 October 1975 | ||||

| Predecessor | Nawwaf bin Abdulaziz Al Saud | ||||

| Successor | Mohammed bin Ali Aba Al Khail | ||||

| Monarch |

| ||||

Prime Minister |

| ||||

| Minister of Interior | |||||

| In office | 1960 | ||||

| Predecessor | Faisal bin Abdulaziz Al Saud | ||||

| Successor | Abdul Muhsin bin Abdulaziz Al Saud | ||||

| Monarch | Saud | ||||

Prime Minister | Crown Prince Faisal bin Abdulaziz | ||||

| Born | 1922 Riyadh, Sultanate of Nejd | ||||

| Died | 1992 (aged 69–70) Riyadh, Saudi Arabia | ||||

| |||||

| Dynasty | House of Saud | ||||

| Father | Abdul Rahman bin Faisal Al Saud | ||||

| Mother | Amsha bint Faraj Al Ajran Al Khalidi | ||||

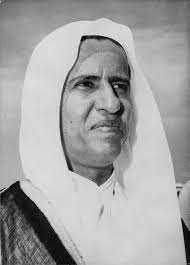

Musaid bin Abdul Rahman Al Saud (Arabic: مساعد بن عبد الرحمن بن فيصل آل سعود Musāʿid bin ʿAbdur Raḥman Āl Saʿūd; 1922 – 1992) was a Saudi Arabian statesman and official who served as the Saudi Arabian minister of interior in 1960 and as the minister of finance from 1962 to 1975.[1] A member of the House of Saud, he was the son of Abdul Rahman bin Faisal Al Saud and Amsha bint Faraj Al Ajran Al Khalidi. Prince Musaid was one of the younger half-brothers of King Abdulaziz and was one of the senior royals who shaped the succession of the rulers during his lifetime.[2]

Early life and education

[edit]Musaid bin Abdul Rahman was born in Qasr Al Hukm, Riyadh,[3] around 1922.[4][5] He was the son of the former emir of Nejd Abdul Rahman bin Faisal and Amsha bint Faraj Al Ajran Al Khalidi.[6] He had a number of half-siblings from his father's other marriages.[7] One of them was King Abdulaziz and others, Muhammad, Abdullah, and Ahmed, served in the Saudi government.[8]

Prince Musaid attended the Mufirej school founded by Sheikh Abdul Rahman Al Mufirej in 1879 which was based in the Sheikh Abdullah bin Abdul Latif mosque in the Dukhna neighborhood of Riyadh.[9] His religious educators included Sheikh Saad bin Ateeq, Hamad bin Faris, Muhammad bin Abd al Latif, Muhammad bin Ibrahim, Ibn Sahman and others.[5] Several sources indicate that he was the only son of Abdul Rahman who received university-level education.[5][6][10]

Career

[edit]Prince Musaid held several governmental positions. He was among the advisors of King Abdulaziz and King Saud.[5][11] He was made the head of the bureau of grievances in 1954 when it was established.[12][13] His appointment was not announced in Saudi newspapers, but in a Bahraini newspaper, Al Qafilah, on 12 November 1954.[13] The bureau was responsible for dealing with all complaints submitted by the citizens against any administrative action, including the examination of each complaint and suggesting the necessary steps to be taken.[14] In 1955 the bureau became an independent unit, and its president, Prince Musaid, was promoted to the rank of minister.[12] It was based in Riyadh with a branch in Jeddah.[15]

Prince Musaid was also the chief of Royal Diwan during the reign of King Saud and accompanied him in his state visit to the US in 1957.[16] In 1960 Prince Musaid briefly served as the minister of interior.[4] Then he was named as the minister of finance on 15 March 1962, replacing his nephew Prince Nawwaf in the post.[4][17] He was reappointed to the post on 31 October 1962, when the cabinet was formed by Crown Prince Faisal.[18] On the request of Crown Prince, Prince Musaid identified the eligible members within the royal family to receive a stipend in 1963.[19] At the beginning of King Faisal's reign Prince Musaid became a member of the council, which had been established by the king to guide the succession issues.[20]

Prince Musaid's tenure as minister of finance ended on 14 October 1975[21] when he was dismissed from the office by King Khalid.[22] He was replaced by Mohammed bin Ali Aba Al Khail in the post.[21] There is another report arguing that Prince Musaid requested to be removed from the post citing his health condition.[23] On the other hand, during the reign of King Khalid, Prince Musaid was one of the members of the inner family council which was led by King Khalid and included Prince Musaid's half-brother Prince Ahmed and his nephews Prince Mohammed, Crown Prince Fahd, Prince Abdullah, Prince Sultan, and Prince Abdul Muhsin.[24]

Personal life and death

[edit]One of his spouses was Tahani bint Abdul Sattar Al Khatib who died in March 2018.[10][11] She was the mother of Hassan bin Musaid.[10] Prince Musaid's other sons are Abdullah (born 1945), Khalid, Faisal and Muhammad.[25][26] Of them Abdullah and Khalid are businessmen.[26][27] His daughter, Noura bint Musaed, married her cousin, Abdul Rahman bin Abdullah bin Abdul Rahman,[25] who was one of the members of Al Saud Family Council established in June 2000 by Crown Prince Abdullah to discuss private issues.[28] Noura bint Musaid died in July 2016.[25]

Prince Musaid's private library with rare book collections in Riyadh was made by him as the first public library in the country.[5] Following his death his books were donated to the library of Imam Muhammad bin Saud Islamic University in Riyadh.[5]

Prince Musaid died in 1992 at age 70 in King Faisal Specialist Hospital in Riyadh.[5]

References

[edit]- ^ Dana Adams Schmidt (12 May 1962). "Saudi Oil Money Put to New Uses: King and Faisal Build Public Welfare and Economy". The New York Times. ProQuest 116058604. Retrieved 30 August 2020.

- ^ Nabil Mouline (April–June 2010). "Power and Generational Transition in Saudi Arabia". Critique Internationale. 46. doi:10.3917/crii.046.0125.

- ^ ""قصر الحكم" يحتفظ بأجمل الذكريات لأفراد الأسرة ... - جريدة الرياض". Al Riyadh (in Arabic). 23 May 2007. Retrieved 26 October 2020.

- ^ a b c J. E. Peterson (2003). Historical Dictionary of Saudi Arabia (2nd ed.). Lanham, MD: Scarecrow Press. p. 100. ISBN 9780810827806.

- ^ a b c d e f g "الأمير مساعد بن عبدالرحمن.. رجل العلم والإدارة". Al Jazirah (in Arabic). 24 October 2010. Archived from the original on 23 March 2019. Retrieved 30 August 2020.

- ^ a b Rashid Saad Al Qahtani. "مساعد بن عبدالرحمن أمير الفكر والسياسة والإدارة". Arabic Magazine (in Arabic). Retrieved 30 August 2020.

- ^ Alexei Vasiliev (2013). King Faisal: Personality, Faith and Times. London: Saqi. p. 12. ISBN 978-0-86356-761-2.

- ^ Christopher Keesee Mellon (May 2015). "Resiliency of the Saudi Monarchy: 1745-1975" (Master's Project). American University of Beirut. Beirut. hdl:10938/10663. Retrieved 23 January 2021.

- ^ "من أعلام الراوي - خاص - مدارات ونقوش". Jamal bin Howaireb Studies Center (in Arabic). Archived from the original on 7 June 2019. Retrieved 13 September 2020.

- ^ a b c وفاة الأميرة تهاني والدة الأمير حسان بن مساعد بن عبدالرحمن آل سعود. Marsad News (in Arabic). 31 March 2018. Retrieved 30 August 2020.

- ^ a b Sharaf Sabri (2001). The House of Saud in Commerce: A Study of Royal Entrepreneurship in Saudi Arabia. Delhi: I. S. Publications. p. 198. ISBN 978-81-901254-0-6.

- ^ a b Maren Hanson (August 1987). "The Influence of French Law on the Legal Development of Saudi Arabia". Arab Law Quarterly. 2 (3): 272–291. doi:10.1163/157302587X00318. JSTOR 3381697.

- ^ a b Charles W. Harrington (Winter 1958). "The Saudi Arabian Council of Ministers". The Middle East Journal. 12 (1): 1–19. JSTOR 4322975.

- ^ Hisham Mosely (June 1973). The rule of the bureaucracy and the development of the kingdom of Saudi Arabia (MA thesis). California State University, Northridge. hdl:10211.2/4506.

- ^ Samir Shamma (July 1965). "Law and lawyers in Saudi Arabia". International and Comparative Law Quarterly. 14 (3): 1034–1039. doi:10.1093/iclqaj/14.3.1034. JSTOR 757066.

- ^ Helmut Mejcher (2004). "King Faisal ibn Abdul Aziz Al Saud in the arena of world politics: A glimpse from Washington, 1950 to 1971". British Journal of Middle Eastern Studies. 31 (1): 5–23. doi:10.1080/1353019042000203412. S2CID 218601838.

- ^ "Chronology December 16, 1961-March 15, 1962". The Middle East Journal. 16 (2): 207. Spring 1962. JSTOR 4323471.

- ^ "Chronology September 16, 1962 – March 15, 1963". The Middle East Journal. 17 (1–2): 133. Winter–Spring 1963. JSTOR 4323557.

- ^ Mordechai Abir (April 1987). "The Consolidation of the Ruling Class and the New Elites in Saudi Arabia". Middle Eastern Studies. 23 (2): 150–171. doi:10.1080/00263208708700697.

- ^ David Rundell (2020). Vision or Mirage: Saudi Arabia at the Crossroads. London; New York: Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 63. ISBN 978-1-83860-594-0.

- ^ a b "Previous Ministers". Ministry of Finance. Archived from the original on 20 September 2020. Retrieved 30 August 2020.

- ^ Joseph A. Kechichian (2014). 'Iffat Al Thunayan: an Arabian Queen. Brighton: Sussex Academic Press. p. 81. ISBN 9781845196851.

- ^ Gary Samuel Samore (1984). Royal Family Politics in Saudi Arabia (1953-1982) (PhD thesis). Harvard University. p. 351. ProQuest 303295482.

- ^ Gulshan Dhahani (1980). "Political Institutions in Saudi Arabia". International Studies. 19 (1): 59–69. doi:10.1177/002088178001900104. S2CID 153974203.

- ^ a b c "بالصور.. أمير الرياض يؤدي صلاة الميت على الأميرة نورة بنت مساعد بن عبد الرحمن". Hasa News (in Arabic). 25 July 2016. Retrieved 30 August 2020.

- ^ a b Who's Who in the Arab World 2007-2008 (18th ed.). Beirut: Publitec Publications. 2007. p. 715. doi:10.1515/9783110930047. ISBN 9783598077357.

- ^ Alan D. Gray (11 July 1974). "Closer ties predicted result of visit from Saudi Prince". The Gazette. Retrieved 24 January 2021.

- ^ Simon Henderson (August 2009). "After King Abdullah: Succession in Saudi Arabia". The Washington Institute. Retrieved 27 May 2012.

External links

[edit] Media related to Musaid bin Abdul Rahman Al Saud at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Musaid bin Abdul Rahman Al Saud at Wikimedia Commons