This article has been reviewed according to Science X's editorial process and policies. Editors have highlighted the following attributes while ensuring the content's credibility:

fact-checked

peer-reviewed publication

trusted source

proofread

Glass beads indicate Indigenous Americans shaped early transatlantic trade

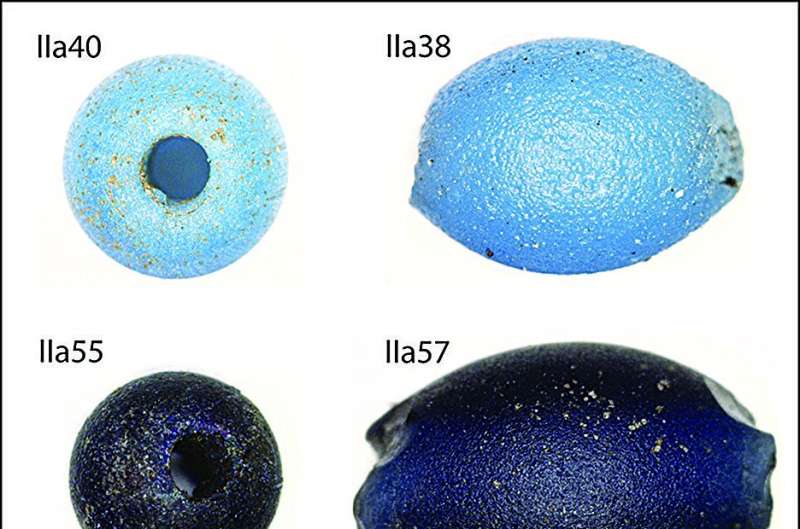

Archaeologists have analyzed the chemical makeup of glass beads from across the Great Lakes region of North America, revealing the extent of Indigenous influence on transatlantic exchange networks during the 17th century AD.

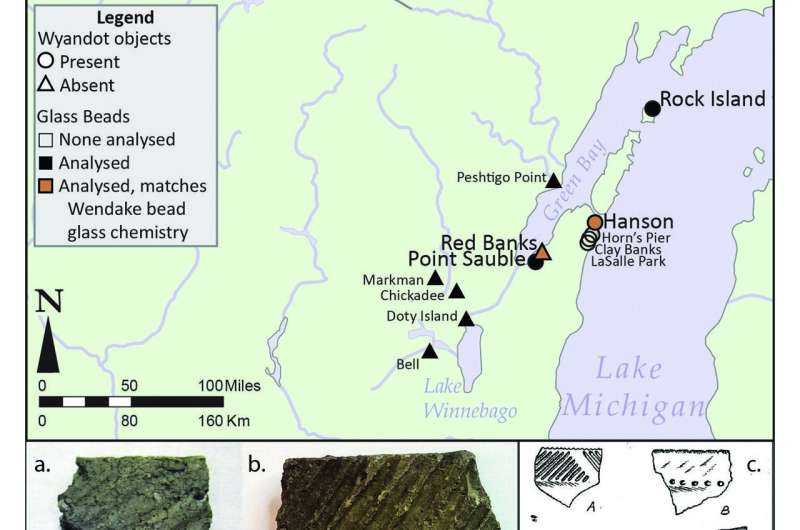

Glass beads were a key component of trade between Europeans and Indigenous Americans during early interactions between the two continents. One of the key actors in these networks was the Wendat Confederacy, which was based in southern Ontario until around 1650, when some Wendat people moved into the Western Great Lakes region.

Beads are a key symbol of European colonization, as they were produced in Europe but had a lasting impact on Indigenous Americans, with beadwork continuing to be integral to many Indigenous cultures to this day.

As such, it was thought that trans-Atlantic bead exchange networks must have been driven by European colonization. The first Europeans colonized the Western Great Lakes region around 1670.

To assess the validity of this idea, Drs Heather Walder and Alicia L. Hawkins, from the Universities of Wisconsin—La Crosse and Toronto Mississauga respectively, examined the chemical compositions of over 1000 17th-century glass artifacts from Europe and eastern North America. Their results are published in the journal Antiquity.

"Previously, archaeologists have studied glass beads to understand the timing of site occupations of the 16th and 17th century," states Dr. Walder. "Instead of treating beads simply as chronological markers, we address their social significance to answer questions about interaction, exchange, and community-level relationships among Indigenous peoples."

They found that glass from different glassmaking centers in Europe is distinguishable by amounts of trace elements, providing a way to determine where the glass beads in North America originated.

This reveals that glass beads in the pre-1650 Western Great Lakes region shared sources with those from Wendat villages hundreds of kilometers away in Ontario. This means that the Wendat were trading beads with the region's inhabitants, the Anishinaabe and other Nations, before they migrated into the area.

Importantly, these results clearly indicate that European glass beads were reaching areas outside of European influence, since significant numbers of French colonizers did not reach the Western Great Lakes region until at least 1670.

Additionally, the colors of beads were changing over time. While white and blue beads were initially most common, later examples are overwhelmingly red; a color favored by the Wendat.

This means that Indigenous Americans were not only incorporating glass beads into their exchange networks, but also influenced bead production in Europe, since the colors of beads changed over time to reflect Indigenous preferences.

"Glass beads can show how Indigenous people maintained social relationships and actively moved as strategies of resilience and resistance during the 17th century in the North American Great Lakes Region," concludes Dr. Walder.

"In short, beads are not (just) clocks. Unlocking their chemical composition using high-tech methods can help us tell stories of the relationships among communities on both sides of the Atlantic Ocean."

More information: Heather Walder et al, Tracking glass beads: communities and exchange relationships across the Atlantic in the seventeenth century, Antiquity (2024). DOI: 10.15184/aqy.2024.80

Journal information: Antiquity

Provided by Antiquity