Summary

Mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathways are major mediators of extracellular signals that are transduced to the nucleus. MAPK signaling is attenuated at several levels and one class of dual-specificity phosphatases, the MAPK phosphatases (MKPs), inhibit MAPK signaling by dephosphorylating activated MAPKs. Several of the MKPs are themselves induced by the signaling pathways they regulate, forming negative feedback loops that attenuate the signals. We show here that in mouse embryos, Fibroblast growth factor receptors (FGFRs) are required for transcription of Dusp6, which encodes MKP3, an extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK)-specific MKP. Targeted inactivation of Dusp6 increases levels of phosphorylated ERK, as well as the pERK target, Erm, and transcripts initiated from the Dusp6 promoter itself. Finally, the Dusp6 mutant allele causes variably penetrant, dominant postnatal lethality, skeletal dwarfism, coronal craniosynostosis and hearing loss; phenotypes that are also characteristic of mutations that activate FGFRs inappropriately. Taken together, these results show that DUSP6 serves in vivo as a negative feedback regulator of FGFR signaling and suggest that mutations in DUSP6 or related genes are candidates for causing or modifying unexplained cases of FGFR-like syndromes.

Keywords: Mkp3, Pyst1, dual specificity phosphatase, craniosynostosis, middle ear, otic capsule

Introduction

Fibroblast growth factors (FGFs) comprise a family of small, highly basic proteins that typically are secreted and bind to and activate high-affinity FGF receptors (FGFRs), a family of single-pass transmembrane proteins with intracellular tyrosine kinase activity. FGF signals are transduced to cellular targets by several distinct intracellular signaling pathways. Cells respond to FGF signals in a context dependent manner; in different instances they may be stimulated to divide, to differentiate, to migrate or to survive. Loss-of-function genetic studies are beginning to reveal the ways in which these FGF-dependent cell behaviors are deployed during the development of many different organs (Itoh and Ornitz, 2004; Thisse and Thisse, 2005). The responses to FGF signals are dose-dependent. Just as a reduction in FGF signals can lead to developmental abnormalities, so too does an increase in FGF signaling. Indeed, some of the most frequently observed human mutations are activating mutations in FGFR genes that cause a variety of dominant skeletal disorders (Cohen, 2004; Wilkie, 2005).

Many FGF signals travel and are amplified through the extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathway. FGF binding stimulates autophosphorylation of the FGFR, which recruits signal adapters and leads to sequential phosphorylation and activation of cytoplasmic protein kinases, ultimately resulting in the di-phosphorylation of ERK on threonine and tyrosine residues. This activated form of ERK has substrates in all cellular compartments, including the nucleus, where it phosphorylates and activates transcription factors, effecting changes in gene expression (Powers et al., 2000; Chen et al., 2001; Tsang and Dawid, 2004; Eswarakumar et al., 2005). Significantly, Corson and colleagues (2003) showed that most of the di-phosphorylated ERK (dpERK, an indicator of ERK pathway activity) in early mouse embryos (E6.5-E10.5) is dependent on FGFR activity. This suggests that FGFs, as opposed to other signals that also act through receptor tyrosine kinases, are the major input into the ERK pathway at these stages.

Signaling through MAPK pathways can be attenuated at several levels and one class of dual-specificity phosphatases, the MAPK phosphatases (MKPs) inhibit MAPK signaling by dephosphorylating activated MAPKs. For example, in S. cerevisiae, mating pheromone-induced signaling through the MAPK, Fus3p, induces the MKP, Msg5p, which feeds back to turn off the signal by inactivating Fus3p (Zhan et al., 1997). Similarly, during Drosophila embryogenesis, signals required for dorsal closure activate the DJNK (basket) MAPK pathway, leading to transcriptional induction of the MKP, puckered, which feeds back to inactivate DJNK and dampen the signal (Martin-Blanco et al., 1998). In addition, Gomez and colleagues (2005) found that Drosophila MKP3 functions as a negative feedback regulator of epidermal growth factor receptor-stimulated ERK signaling during wing vein development.

Mammalian genomes contain at least 11 DUSP genes encoding the MKPs (Alonso et al., 2004), several of which have been analyzed biochemically. Some MKPs are relatively non-specific towards different dpMAPKs in vitro. Other MKPs, however, show substrate specificity, including the structurally related cytosolic MKPs -3 (DUSP6), -X (DUSP7), and -4 (DUSP9), which inactivate dpERK in preference to other activated MAPKs (Camps et al., 2000; Keyse, 2000; Theodosiou and Ashworth, 2002). Dusp6 (also known as Mkp3 or Pyst1) transcripts can, in some circumstances, be induced in cultured cells by growth factors that stimulate the ERK pathway (Mourey et al., 1996; Muda et al., 1996a), but clues to physiologic inducers have come from embryonic expression analyses. We and others noticed that Dusp6/Mkp3 is expressed during embryonic development of several vertebrate species in a pattern that corresponds with areas of active FGF signaling, suggesting that it could be a conserved transcriptional target of FGF signals (Dickinson et al., 2002a; Klock and Herrmann, 2002; Eblaghie et al., 2003; Kawakami et al., 2003; Tsang et al., 2004; Gómez et al., 2005; Li and Mansour, unpublished observations). Indeed, ectopic FGF signals activate Dusp6/Mkp3 transcription in chick, zebrafish and frog embryos, as well as in explanted mouse neural tube cultures; ectopic Dusp6/Mkp3 expression reduces dpERK levels, and local siRNA, global morpholino-mediated knock-down, or dominant negative experiments suggest roles for Dusp6/Mkp3 in chick limb development, axial patterning of zebrafish embryos and anterior development of frog embryos, respectively (Eblaghie et al., 2003; Kawakami et al., 2003; Tsang et al., 2004; Echevarria et al., 2005; Gómez et al., 2005; Smith et al., 2005). Taken together, these results show that Dusp6/Mkp3 can be activated by FGF signaling and suggest a negative feedback role for DUSP6/MKP3 in FGF/ERK signaling, but genetic loss-of-function data are lacking.

To address the hypothesis that mouse DUSP6/MKP3 plays a role in FGF-stimulated ERK signaling analogous to the MKPs that play clearly established negative feedback roles in regulating invertebrate MAPK signaling pathways, we studied Dusp6/Mkp3 expression in FGFR-deficient mouse embryos and generated and analyzed a targeted loss-of-function Dusp6/Mkp3 allele. Our data show that in mouse embryos, Dusp6/Mkp3 transcription depends on FGF signaling and that dpERK is a physiologic DUSP6/MKP3 substrate. Furthermore, we find that loss of Dusp6/Mkp3 leads to dominant, incompletely penetrant and variably expressive phenotypes that have features, including skeletal dwarfism, coronal craniosynostosis and hearing loss, in common with dominant gain-of-function mutations in human and mouse FGFRs.

Materials and methods

Dusp6 is the official symbol for the mouse gene encoding MKP3 (MGI:1914853), and this nomenclature is used from here on.

Whole mount RNA in situ hybridization and dpERK immunohistochemistry

Whole mouse embryos isolated from timed pregnancies were hybridized with digoxigenin-labeled anti-sense RNA probes, which were detected according to Henrique et al. (1995). Stained embryos were cryoprotected and sectioned at 14 μm as described (Wright and Mansour, 2003). The Dusp6 probe was complementary to nucleotides 1-413 of the Dusp6 reference sequence (5′ UTR; GenBank accession NM_02628). The Erm probe was complementary to nucleotides 1309-1766 of the Etv5 reference sequence (GenBank accession NM_023794). The Fgfr1 probe was complementary to nucleotides 1-459 of the Fgfr1 cDNA (5′ UTR; GenBank accession BC010200). The Fgf8, Fgf10, Fgfr2b and Fgfr2c isoform-specific and Fgfr4 probes were generated as described (Wright et al., 2003; Wright and Mansour, 2003; Ladher et al., 2005). Whole mouse embryos were stained with antibodies directed against di-phosphorylated ERK1/2 exactly as described by Corson et al. (2003).

Dusp6 gene targeting

A Dusp6-containing lambda genomic phage was isolated from a strain 129SV/J library (Stratagene). Standard techniques were used to isolate a 6.9 kb fragment containing the entire gene and transform it into a LacZ knock-in gene targeting vector (Fig. 3A). An nlsLacZSV40pA cassette was excised from a gene-trap vector (Yang et al., 1997), excluding the splice acceptor sequence, and inserted into the Dusp6 Msc I site in exon 1, fusing the first 56 codons of the DUSP6 open reading frame (ORF) in-frame with the βgal ORF. A self-excising Neor expression cassette (ACN, Bunting et al., 1999) was placed immediately downstream of the LacZ gene for positive selection of targeted cell lines. In anticipation of the small possibility of spurious transcription initiation from inside the LacZ cassette, followed by translation initiation from an internal Dusp6 AUG and/or the remote possibility of translation initiating downstream of the DUSP6/βGAL ORF on an SV40pA read-through transcript, we added a linker containing a stop codon in the DUSP6 frame into the BstB I site in exon 3. Any hypothetical DUSP6 fragment produced from such transcripts would be missing portions of both the amino- and carboxy-terminal domains that are essential for DUSP6 activity (Camps et al., 1998; Zhou et al., 2001). The targeting construct was flanked by two different thymidine kinase expression cassettes for negative selection. The targeting DNA was linearized and electroporated into R1-45 ES cells. After selection in 380 μg/ml G-418 by weight (Invitrogen) and 2 mM ganciclovir (Sigma), drug resistant colonies were cloned and expanded. DNA isolated from each colony was screened by Southern blot hybridization using Nde I digestion and a 3′ flanking probe. DNAs showing the 7.0 kb targeted band were further screened by PCR with primers 376 (5′-GGTATCAGCCGCTCTGTCAC-3′) and 331 (5′-GGACACGGTTGTCACAAGG-3′) for the presence of the stop codon in exon 3. The wild type allele was 187 bp and the mutant (stop-containing) allele was 198 bp. DNAs from targeted cell lines that carried the stop codon were further analyzed by Southern blotting using a variety of enzymes and probes. Of 192 drug resistant cell lines tested, 12 had a targeted insertion in the Dusp6 locus and of these, 8 also carried the stop codon.

Figure 3.

Gene targeting at the Dusp6 locus. (A) Structure of the linearized Dusp6 targeting vector and depiction of the wild type Dusp6 allele (Dusp6+), the correctly targeted mutant allele in ES cells (Dusp6LACN) and the targeted allele found in mice following expression of CRE in germline-transmitting chimeras (Dusp6L). Mouse genomic Dusp6 DNA is depicted with solid thick lines; dotted lines indicate Dusp6 genomic DNA not present in the targeting vector; open boxes indicate untranslated regions; solid boxes indicate protein coding regions. The LacZ gene (nls-lacZpA) is shown as a dark grey box; the Cre/Neo “suicide cassette” (ACN) as a light grey box; the stop codon in the DUSP6 frame in exon 3 as an asterisk. Flanking thymidine kinase genes (TK1 and TK2, transcriptional orientation indicated by arrows) and the plasmid backbone are depicted as open boxes. Recognition sites for Nde I are indicated by “N”; probes used for Southern analysis by black bars. Numbered arrows indicate the identity, position and directionality of primers used in PCR assays. (B) Southern blot hybridization assay demonstrating correct targeting of Dusp6 in ES cells. Nde I-digested DNA from the R1 ES cell line (R1), a cell line with a random insertion of the targeting vector (Ran) and a targeted cell line (Tar) was probed sequentially with 3′ and Cre probes. Correctly targeted cell lines had a novel 7.0 kb fragment that hybridized with both probes. (C) PCR assay used to detect the stop-codon-containing insertion in exon 3. DNAs isolated from correctly targeted ES cells (Tar), a control random integrant (Ran) and wild type cells (R1) were PCR-amplified using primers 376 and 331. Targeted cell lines (TAR*) that produced both the wild type (187 bp) and the insertion amplicon (198 bp) were selected for germline transmission. (D) PCR assay used to genotype offspring of Dusp6+/L intercrosses. Tail DNAs were PCR-amplified with primers 344, 309 and 315. The mutant allele yielded a 363 bp band and the wild type allele yielded a 499 bp band. (E) Northern blot hybridization of mRNA isolated from E11.5 embryos of the indicated genotypes was probed with a fragment of Dusp6 3′ UTR, revealing a wild type transcript of ∼3 kb in +/+ and +/- samples that was absent from the -/- sample. A minor read-through transcript of ∼7.5 kb was evident in +/- and -/- samples, but due to the targeting strategy, it is incapable of encoding functional DUSP6. Rehybridization with a Gapdh probe is shown below.

Dusp6 mutant mouse generation and genotyping

All work with mice complied with protocols approved by the University of Utah Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Several correctly targeted cell lines were aggregated with C57Bl/6 morulae, cultured overnight and implanted into pseudopregnant females (Khillan and Bao, 1997). Three of these cell lines gave rise to chimeric males that transmitted the targeted allele (less the self-excising Neo cassette) to offspring. In subsequent crosses, the mutant and wild type alleles were distinguished in tail or yolk sac DNA using either of two 3-primer PCR mixes. The mix containing primers 344 (5′-CTGTGTCGCTTTCCCTAACC-3′), 309 (5′-ACGCTGCTGCTGTTGC-3′) and 315 (5′-GACCGACTCTCCACCAGTGT-3′) produced a wild type band of 499 bp and a mutant band of 363 bp. The mix containing primers 344 (as above), 357 (5′-CCAGGGTTTTCCCAGTCA-3′) and 430 (5′-CTAGCTCCCCTAAGCGCAAT-3′) produced a wild type band of 661 bp and a mutant band of 522 bp. No difference between intercross offspring produced from different targeted cell lines was immediately apparent; so one line was selected for all further analysis and backcrossing.

Mice carrying the Fgfr1α (Fgfr1tm1Cxd, MGI:2153353) and Fgfr2ΔIgIII (Fgfr2tm1Cxd, MGI:2153790) hypomorphic alleles were generously provided by Dr. Chuxia Deng and genotyped as described (Xu et al., 1998; Xu et al., 1999).

Northern blot hybridization

Total RNA was isolated from E11.5 embryos or adult brains, mRNA was purified and 3 μg of each genotype was analyzed by Northern blot hybridization according to standard protocols (Yang et al., 2001). The 448 bp 3′ UTR probe was generated by PCR amplification of mouse genomic DNA with primers 311 (5′-ACCCCTTGAGACACTGTAAGC-3′) and 329 (5′-GGGTATAGTGGAGCCAAAGAGA-3′). The 5′ UTR probe was the same as that used for in situ hybridization. The LacZ probe was generated by PCR amplification of plasmid DNA with primers 24 (5′-GGGTTGTTACTCGCTCACA-3′) and 25 (5′AAAGCGAGTGGCAACATGG-3′)

Skeleton preparation, computed tomography scanning and bone histology

To visualize the skeleton, animals were asphyxiated in CO2, skinned, fixed in 95% ethanol, defatted in acetone and then stained with Alcian Blue 8GX and Alizarin Red S and cleared as described (Mansour et al., 1993). MicroCT scans of pups sacrificed at P10 were performed as described (Keller et al., 2004). Cranial vault measurements were made using reconstructed mid-sagittal sections. For bone histology, the proximal tibial metaphyses were stained en bloc with Villanueva bone stain, dehydrated in graded concentrations of alcohol, defatted in acetone, and embedded in methyl methacrylate monomer. Longitudinal frontal sections of the tibia were cut at 4 μm. One set of sections was stained with 5% silver nitrate and counterstained with 0.5% basic fuchsin, another set of sections was stained with 0.1% toluidine blue O (Jee et al., 1997).

Auditory Brainstem Response threshold measurements

Mice were anesthetized using 0.02 ml/g Avertin. ABR thresholds for click (47 μsec), 8 kHz, 16 kHz, and 32 kHz tone pip stimuli (3000 μsec, Exact Blackman envelope) were determined according to Zheng et al. (1999), using high frequency transducers controlled and analyzed by SmartEP software (Intelligent Hearing Systems).

Results

Dusp6 is expressed in areas of active signaling through the FGFR/ERK pathway

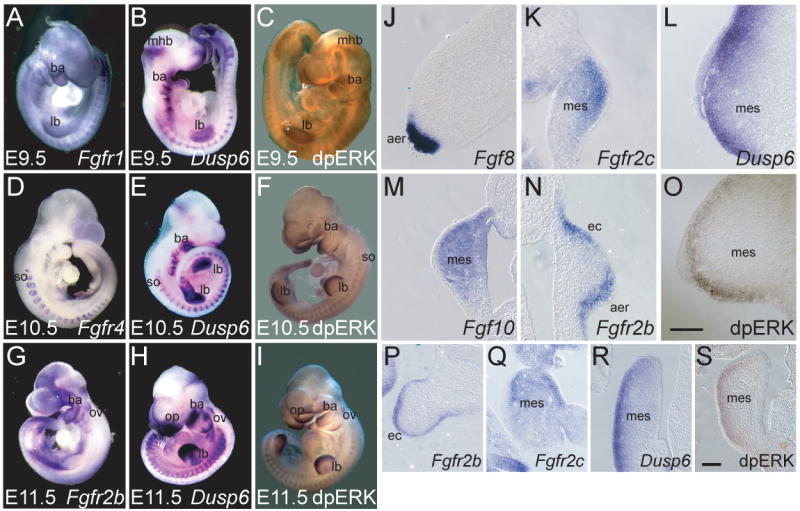

It has been noted previously that in mouse, chick and zebrafish embryos, Dusp6 (also known as Mkp3) is expressed in cells adjacent to those expressing Fgfs, particularly Fgf8, suggesting that transcription of Dusp6 is regulated by FGF signals (Dickinson et al., 2002a; Klock and Herrmann, 2002; Eblaghie et al., 2003; Kawakami et al., 2003; Tsang et al., 2004). Areas of the embryo potentially competent to respond to FGF signals can be recognized by their expression of FGF receptor genes (Fgfrs). If Dusp6 is a transcriptional target of FGF signaling, then it should be co-expressed with Fgfrs. We found that between E9.5 and E11.5, Dusp6 expression was highly correlated with several areas of Fgfr expression (Fig. 1). For example, Fgfr1 and Dusp6 were expressed in the branchial arches and limb buds at E9.5 (Fig. 1A,B), Fgfr4 and Dusp6 were expressed in the somites at E10.5 (Fig. 1D,E) and Fgfr2b and Dusp6 were expressed in the branchial arches and otic vesicle at E11.5 (Fig. 1G,H).

Figure 1.

Dusp6 expression correlates with particular Fgfrs and with most areas of dpERK expression. (A,D,G) Whole mount RNA in situ hybridization (WmISH) of mouse embryos with the Fgfr probes indicated at the bottom right of each panel. (B,E,H) WmISH of embryos with a Dusp6 probe. (C,F,I) Whole mount immunostaining of embryos with antibody directed against diphosphorylated ERK (dpERK). Embryo age is indicated at the bottom left of each panel. (J-R) Transverse sections of E10-E10.5 WmISH embryos illustrating potential FGF signaling pathways in the limb bud (J-O) and branchial arches (P-R). Probes are noted at the bottom left of each panel. Abbreviations: ba, branchial arches; lb, limb bud; mhb, mid-hindbrain junction; so, somites; ov, otic vesicle; op, olfactory pit; aer, apical ectodermal ridge; ec, ectoderm; mes, mesenchyme.

One of the intracellular pathways by which activated FGF receptors signal to the nucleus, is the ERK pathway, activation of which can be visualized by immunostaining for dpERK. Indeed, most expression domains of dpERK in E7.5-E10.5 mouse embryos depend on FGF signaling (Corson et al., 2003). If Dusp6 is a transcriptional target of FGF signaling through the ERK pathway, then it should be co-expressed with dpERK. We found that there was a striking correlation between the dpERK and Dusp6 expression domains between E9.5 and E11.5 (Fig. 1). For example, dpERK and Dusp6 were found in the limb buds, branchial arches and mid-hindbrain boundary at E9.5 (Fig. 1B,C), in the somites, limb buds and branchial arches at E10.5 (Fig. 1E,F) and in the limb buds, branchial arches, otic vesicles and olfactory pits at E11.5 (Fig. 1H,I).

Sections taken through the developing limb buds (Fig. 1J-O) and branchial arches (Fig. 1P-S) at E10-E10.5 illustrate potential FGF signaling pathways in more detail. In the limb, the genes encoding the ligands FGF8 (Fig. 1J) and FGF10 (Fig. 1M) were expressed in the apical ectodermal ridge (aer) and mesenchyme (mes) respectively. FGF8 and FGF10 could signal to their preferred receptors, mesenchymal FGFR2c (Fig. 1K) and ectodermal FGFR2b (Fig. 1N), respectively. Dusp6 and dpERK were primarily mesenchymal (Fig. 1L,O), suggesting that they may participate in the mesenchymal response to FGF signals. Similar FGF signaling pathways were present in the branchial arches. FGF8 and FGF10 were ectodermal and mesodermal, respectively (data not shown), whereas genes encoding their receptors, FGFR2c (Fig. 1Q) and FGFR2b (Fig. 1P), were expressed in the mesoderm and ectoderm, respectively. As in the limb bud, branchial arch Dusp6 and dpERK were primarily mesenchymal (Fig. 1R,S). Taken together, these data show that Dusp6 expression correlates with Fgfr expression domains and with sites of FGF-activated ERK signaling in the mesenchyme.

Dusp6 expression in mouse embryos depends on FGF signaling

Ectopic activation of FGF signaling in zebrafish and chick embryos or mouse neural tube explants is sufficient to induce ectopic Dusp6 expression (Eblaghie et al., 2003; Kawakami et al., 2003; Tsang et al., 2004; Echevarria et al., 2005; Smith et al., 2005). Furthermore, genetic or physical ablation of FGF4 and FGF8 signals from the apical ectodermal ridge in mouse, chick and zebrafish embryos (Eblaghie et al., 2003; Kawakami et al., 2003), application of the FGF receptor inhibitor SU5402 to developing chick somites or mouse neural tube explants (Smith et al., 2005; Vieira and Martinez, 2005), or expression of dominant negative FGF receptors in zebrafish embryos (Tsang et al., 2004) reduces endogenous Dusp6 expression in the target tissue. To determine whether FGF signaling is required globally for Dusp6 transcription in mouse embryos, we assayed Dusp6 expression by in situ hybridization of whole mouse embryos homozygous for hypomorphic mutations in either Fgfr1 or Fgfr2 (Xu et al., 1998; Xu et al., 1999). Dusp6 transcripts were severely reduced in both E9.5 Fgfr1α (Fig. 2A, B) and E8.5 Fgfr2ΔIgIII (Fig. 2C-H) homozygous embryos relative to similarly staged control embryos stained under identical conditions. These data show that Dusp6 expression requires signaling through FGFR1 or FGFR2.

Figure 2.

Dusp6 expression depends on signaling through FGF receptors. WmISH of wild type and homozygous Fgfr hypomorphic (h) mutant littermates with a Dusp6 probe (A,B) Fgfr1α, E9.5; (C-H) Fgfr2ΔIgIII, E8.5. Genotype of each embryo is indicated in the upper left of each panel.

Gene targeting at the Dusp6 locus

If Dusp6 is a transcriptional target of FGF-activated signaling through the ERK pathway and its biochemical function is to inactivate dpERK, then ablation of Dusp6 should lead to an increase in FGF-activated ERK signaling. Indeed, Dusp6 morpholino-injected zebrafish embryos exhibit axial patterning phenotypes similar to those induced by ectopic Fgf8 expression (Tsang et al., 2004). To determine the role of mouse Dusp6, its function was disrupted using standard gene targeting techniques to insert an in-frame LacZ cassette into the first coding exon and a stop codon in the third exon (Fig. 3A). Correctly targeted ES cell lines were identified by Southern blot hybridization analysis of Nde I-digested DNA using 3′ flanking and internal Cre probes (Fig. 3B). Additional digestions and probes confirmed the expected structure of the targeted allele (data not shown). Correctly targeted cell lines were further screened for the presence of the stop codon by PCR using primers flanking the newly introduced stop codon (Fig. 3C). During germline transmission of the correctly targeted, stop codon-containing allele, the Neo gene was automatically deleted and this was confirmed by Southern hybridization analysis (data not shown). The LacZ knock-in allele was designated Dusp6L. A 3-primer PCR assay was developed to distinguish the wild type (+) and mutant (-) alleles (Fig. 3D).

To determine the efficacy of the disruption strategy, we hybridized a Northern blot of E11.5 mRNAs with a Dusp6 exon 3 3′ UTR probe (Fig. 3E). The expected ∼3 kb Dusp6 transcript and an uncharacterized, weakly expressed ∼4 kb transcript were evident in wild type and heterozygous samples, but were absent from homozygous mutant mRNA, showing that the targeting strategy effectively disrupted production of Dusp6 mRNA. A novel, low-abundance transcript of ∼7.5 kb was apparent in heterozygous and mutant samples. This is the expected size for mutant transcripts initiated at the Dusp6 promoter and terminated at the Dusp6, rather than the SV40 polyadenylation signal, followed by removal of the Dusp6 introns (see Fig. 4G,I for further hybridization data supporting this interpretation). Even if translation of this ∼7.5 kb fusion mRNA could initiate at a Dusp6 AUG codon downstream of the DUSP6/βgal ORF, a functional DUSP6 protein could not be produced from the mutant allele, as portions of both the amino and carboxy-terminal regulatory domains required for DUSP6 activity would be absent (Camps et al., 1998; Zhou et al., 2001). Thus, the targeted allele is likely to be null.

Figure 4.

DUSP6 is a negative feedback regulator of the ERK pathway. (A-C) Immunostaining of wild type and Dusp6-/- embryos with anti-dpERK. (A) An E9.5 Dusp6-/- embryo has increased levels of dpERK in the limb (black arrow) relative to that of a wild type embryo (white arrow). (B) Limb bud of wild type E10.5 embryo. (C) Limb bud of Dusp6-/- embryo with increased levels of dpERK. (D-F) RNA in situ hybridization of E10.5 embryos shows increasing levels of Erm transcripts as Dusp6 levels decrease. Genotype of each embryo is indicated in the lower left of each panel. Northern blot hybridization of mRNA isolated from pooled E11.5 embryos (G) or individual adult brains (H) of the indicated genotypes and probed sequentially with a Dusp6 5′ UTR probe, a LacZ probe, and Gapdh, shows that embryos lacking Dusp6 have increased levels of transcripts initiated from the Dusp6 promoter. Note that the embryonic Gapdh panel is identical to the one shown in Figure 3E, because it comes from the same blot. (I) Diagrams of the transcripts produced by wild type (Dusp6+) and mutant (Dusp6L) alleles and the locations of the probes (bars above transcripts) used for hybridization. Open boxes, untranslated Dusp6 sequence; black boxes, DUSP6 coding sequence; grey box, LacZ cassette.

One objective of the LacZ knock-in strategy was to enable a simple reporter assay for Dusp6 expression. Surprisingly, we found that heterozygous embryos exhibited little or no βgal activity, whereas homozygous E10.5-E16.5 embryos produced readily detectable βgal in a pattern that largely, though not perfectly, mimicked that of transcripts detected by whole mount in situ hybridization in embryos of both genotypes by using either Dusp6 5′ UTR or LacZ probes (data not shown, but see Fig. 4G for Northern data). This apparently post-transcriptional phenomenon is under investigation.

Dusp6 is not required for embryonic development, but has incompletely penetrant effects on dpERK, Erm and Dusp6 levels

To assess the role of Dusp6 in embryonic development, the F1 Dusp6+/L offspring of germline chimeras were intercrossed and embryos were collected and genotyped between E8.5 and E17.5. Of 1160 intercross offspring, 244 were wild type, 459 were heterozygous, 226 were homozygous mutant and 11 genotypes could not be determined. These results are consistent with a normal Mendelian distribution of wild type and mutant alleles. No obvious abnormalities were seen in embryos of any genotype, indicating that Dusp6 does not have a unique and visibly evident function during embryonic mouse development.

DUSP6 has a high degree of substrate specificity in vitro, dephosphorylating dpERK in preference to other MAP kinases (Groom et al., 1996; Muda et al., 1996b). To determine whether ERK signaling was perturbed in homozygous mutants, we stained whole embryos at E9.5 and E10.5 with antibodies directed against dpERK in parallel with wild type littermate control embryos. In 4 out of 8 homozygotes analyzed, the extent of dpERK staining was increased, particularly in the limb (Fig. 4A-C). In the remaining cases, no differences in dpERK staining between wild type and homozygous mutant embryos could be discerned (data not shown). Thus, as predicted, DUSP6 dephosphorylates dpERK in vivo.

One of the responses to activation of the ERK pathway is an increase in Erm transcripts (Raible and Brand, 2001; Roehl and Nüsslein-Volhard, 2001; Firnberg and Neubüser, 2002; Liu et al., 2003). To determine whether Erm expression was affected in Dusp6 mutants, we subjected E10.5 embryos (9 of each genotype) to RNA in situ hybridization analysis with an Erm probe. After an identical staining reaction, stopped when Erm transcripts were just becoming evident in wild type embryos (Fig. 4D), 3 out of 9 heterozygous embryos had greater Erm expression (Fig. 4E) and 3 out of 9 homozygotes had even more Erm signal (Fig. 4F). No differences from wild type controls were apparent in the remaining heterozygous or homozygous embryos. These results confirm that inactivation of Dusp6 can increase signaling through the ERK pathway. Furthermore, the intermediate phenotype seen in heterozygotes suggests that signaling through the ERK pathway to induce Erm is sensitive to the level of Dusp6.

If DUSP6 has a negative feedback role in ERK signaling, transcription from its promoter should be increased in Dusp6 mutants. Northern hybridization analysis of E11.5 mRNA samples using a Dusp6 5′ UTR probe located upstream of the LacZ insertion showed a small increase in Dusp6-initiated transcripts present in homozygous mutant mRNA relative to wild type and heterozygous samples (Fig. 4G, note levels of the Gapdh control hybridization). A second, independent comparison between genotypes showed equivalent levels of Dusp6 5′UTR-containing transcripts (data not shown), presumably because multiple embryos of the same genotype were pooled to prepare the mRNA samples and the phenotype was variable. More strikingly, a similar hybridization analysis of mRNA prepared from individual adult brain samples showed a notable increase in Dusp6 5′ UTR-containing transcripts in homozygous mutant samples relative to wild type and heterozygous samples (n=2 out of 4, Fig. 4H). Also as expected, in both embryonic and adult sources of mRNA, the LacZ probe detected transcripts from the mutant allele of ∼5 kb and ∼7.5 kb, reflecting production of Dusp6/LacZ fusion transcripts with polyadenylation likely occurring at the SV40 or Dusp6 polyadenylation sites, respectively (Fig. 4G-I). This result shows that Dusp6 transcription is subject to negative autoregulation.

Loss of Dusp6 results in dominant, incompletely penetrant postnatal lethality

To determine whether Dusp6 is required for any aspect of postnatal development, Dusp6+/L offspring of chimeric males and C57Bl/6 females were produced and offspring of these F1 Dusp6+/L intercrosses were genotyped at weaning (∼4 weeks postnatal). The numbers of wild type and heterozygous F1 progeny of the chimeras did not deviate significantly from those expected (Table 1). In contrast, of 580 F1 intercross offspring genotyped, 168 were wild type, 287 were heterozygotes and only 125 were homozygotes (Table1), all of which appeared normal. This genotypic distribution deviated slightly, but significantly from the Mendelian expectation (P = 0.04) and suggested reduced viability of homozygotes and possibly even heterozygotes. Increasing the C57Bl/6 contribution to the genetic background by crossing F1 heterozygotes to C57Bl/6 animals caused a significant reduction in the observed numbers of heterozygous offspring relative to wild type. Of 540 F1 × C57Bl/6 offspring, 309 were wild type and only 231 were heterozygous (P = 0.00078, Table 1). The genotypic distribution of the F2 Dusp6+/L intercross offspring was even more significantly distorted than that of the F1 intercross. Among 505 total offspring, 142 were wild type, 269 were heterozygous and 94 were homozygous mutant (P = 0.0036, Table 1). The very mixed genetic background of this intercross may explain why the heterozygous lethality seen in the backcross was not obvious. Taken together, these breeding results suggest that the Dusp6 mutation is associated with dominant, but incompletely penetrant postnatal lethality that is exacerbated on the C57Bl/6 background.

Table 1.

Dusp6 backcross and intercross genotypes.

| Genotype at Weaning | Chimera X Bl/6 | F1 X Bl/6 |

|---|---|---|

| +/+ | 177 | 309 |

| +/- | 169 | 231 |

| Total | 346 | 540 |

| P value | 0.67 | 0.00078 |

| F1 intercross | F2 intercross | |

| +/+ | 168 | 142 |

| +/- | 287 | 269 |

| -/- | 125 | 94 |

| Total | 580 | 505 |

| P value | 0.04 | 0.0036 |

Offspring of the indicated crosses were genotyped at weaning. P values were determined using the method of X2. Significant P values are bolded.

Loss of Dusp6 causes skeletal dwarfism

Observations of F1 intercross litters prior to weaning indicated that most litters had pups that appeared smaller than their littermates after about P5. Therefore, we collected and genotyped intercross pups between P5 and P16. Pups were scored as small if their weight was less than 75% of the littermate average. An example of a small P10 heterozygote and its normally sized wild type littermate is shown in Figure 5A. Of 115 intercross offspring (predominantly from the F1 intercross, but including some litters from the F2 intercross), 31 were wild type (3 small), 60 were heterozygous (4 small), 23 were homozygous mutant (10 small) and 1 could not be genotyped because it was cannibalized after initial observation. This genotypic distribution was not significantly different from the Mendelian expectation, but about 40% of the P5-P16 homozygotes were small. Small homozygous or heterozygous animals were not routinely observed prenatally or at weaning, suggesting that pre-weaning lethality of the subset of small heterozygous or homozygous individuals can account for the reduced number of these animals genotyped at weaning.

Figure 5.

Reduction or loss of Dusp6 can result in skeletal dwarfism, altered growth plates, coronal craniosynostosis, and delayed ossification of the phalanges. (A) Small Dusp6+/L P10 pup (+/L) and wild type (+/+) littermate. (B-E) 4 μm frontal sections of undecalcified P14 proximal tibia from wild type and small Dusp6L/L pups stained with silver nitrate and basic fuchsin. (B,C) The ossification (oz), hypertrophic (hz), and proliferation (pz) zones are indicated. Scale bar: 0.5 mm. Higher magnification views of toluidine blue-stained sections of wild type (D) and mutant (E) growth plates. Scale bar: 0.2 mm (F-I) Dorsal views (anterior is to the left) of alizarin red (bone) and alcian blue (cartilage)-stained skulls of P5 and P10 pups. Black arrows in F and H indicate the open coronal sutures in wild type skulls and white arrows in G and I indicate the fused coronal sutures in small homozygous and heterozygous mutant pups, respectively. (J-M) Dorsal views of P0 and P5 control and small heterozygous or homozygous mutant autopod skeletons. (J,K) Right hands, black and grey arrows indicate the presence and absence, respectively of the primary ossification center of the middle phalanx of the fifth digit. (L,M) Right feet, black and grey arrows indicate the presence and absence, respectively of the primary ossification centers of the middle phalangeal ossification centers for digits 2-4. Age and genotype are indicted to the lower left and lower right of each panel, respectively.

Since small Dusp6 mutants did not appear to have any physical impediments to feeding, such as malocclusion or cleft palate (data not shown), we examined their long bones for disturbances of the growth plate. The proximal tibia of a P14 wild type animal had typical histology, with well-ordered chondrocytes proceeding through proliferative, hypertrophic and ossification stages (Fig. 5B,D). In contrast, the proximal tibia of a small P14 Dusp6-/- pup had severely reduced hypertrophic and ossification zones (Fig. 5C). In addition, chondrocytes in the mutant proliferating zone were disorganized; they did not form typical long straight columns of cells (Fig. 5E). This phenotype was observed in all three small mutants examined and is very similar to that of mice bearing activating mutations in FGFR3 (Brodie and Deng, 2003).

Loss of Dusp6 causes craniosynostosis

Mildly activating mutations in FGFR1 and FGFR2 typically cause craniosynostoses (premature fusions of the cranial sutures) in humans and mice, and hand and foot malformations in humans. In addition, the P250R substitution in FGFR3 causes “non-syndromic” craniosynostosis in humans (Zhou et al., 2000; Brodie and Deng, 2003; Chen et al., 2003; Wang et al., 2005; Wilkie, 2005). Therefore, we examined small Dusp6+/L and Dusp6L/L animals for additional phenotypes associated with activation of FGF signaling. Staining the carcasses of small P5-P15 animals to reveal cartilage and bone showed coronal craniosynostosis in small heterozygous and homozygous individuals (Fig. 5G,I), but not in wild type (Fig. 5F,H) or normally sized Dusp6+/L or Dusp6L/L pups (data not shown). Furthermore, microCT scanning of small P10 Dusp6+/L and Dusp6L/L skeletons showed that the skull vault height:length and height:width ratios were significantly larger than those of the corresponding wild type control ratios, which is consistent with mild craniosynostosis (Table 2).

Table 2.

MicroCT scanning measurements of wild type and small heterozygous or homozygous mutant P10 skulls

| Genotype | Length

(mm) |

Height

(mm) |

Width

(mm) |

H:L | H:W | W:L |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| +/+

n=4 |

12.75

+/- 0.80 |

6.00

+/- 0.25 |

9.25

+/- 0.15 |

0.47

+/- 0.02 |

0.65

+/- 0.02 |

0.73

+/- 0.01 |

| small +/L | 11.40 | 6.22 | 8.70 | 0.55 | 0.72 | 0.76 |

| small L/L | 12.16 | 6.39 | 8.52 | 0.53 | 0.75 | 0.70 |

The wild type control measurements for cranial vault measurements are presented as an average in mm +/- 1 standard deviation. H, height; L, length; W, width.

In contrast, no obvious hand or foot malformations were apparent (data not shown), but the ossification sequence of the phalanges was slightly delayed in small animals. For example, at P0, the primary ossification center of the middle phalanx of the fifth digit of the hand was clearly visible in a wild type pup, but had not yet ossified in its small heterozygous littermate (Fig. 5J,K). In addition, all of the middle phalangeal ossification centers for digits 2-4 could be seen in wild type feet, but were not yet ossified in a small heterozygous littermate (Fig. 5L,M). By P5, ossification in small heterozygotes or homozygotes resembled that of wild type littermates (data not shown). Thus, reduction or loss of Dusp6 caused at least two phenotypes, skeletal dwarfism and craniosynostosis, which are also consequences of activated FGF signaling, but this mutation was not associated with significant distal limb malformations.

Loss of Dusp6 causes hearing loss

Clinical descriptions of patients with dominant, activating FGFR mutations often include reports of sensorineural and/or conductive deafness (Gorlin, 2004). Therefore, we measured auditory brainstem response (ABR) thresholds at about 6 weeks of age in normally sized animals of all three Dusp6 genotypes, but no significant differences between genotypes were observed (data not shown). In addition, five small intercross offspring survived to 21-28 days and could be evaluated for an ABR. Four of the five small animals had ABR thresholds that were significantly elevated in one or both ears relative to wild type littermate and other similarly aged control mice (Table 3). Examination of inner ear histology from a small heterozygote (I607) with bilaterally increased ABR thresholds did not reveal any obvious abnormalities relative to a normal hearing control littermate, whereas in another small bilaterally affected heterozygote (I1034), the opening of the middle ear cavity, to which the tympanic membrane attaches, was distorted (Fig. 6A,B). That animal had ossicles that appeared normal (data not shown). Similar results were obtained for the left (affected) ear of the unilaterally affected heterozygote, I1008. Another unilaterally affected homozygote (I919) died unattended before any tissues could be recovered for analysis.

Table 3.

Auditory brainstem response threshold measurements for small Dusp6 mutant pups.

| Stimulus |

Dusp6+/+ controls, mean Db +/- SD

(n=13) |

I607 Dusp6+/- | I642 Dusp6-/- | I919 Dusp6-/- | I1034 Dusp6+/- | I1008 Dusp6+/- |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| L click | 35.4 +/- 3.2 | 70* | 40 | 60* | NR* | 50* |

| R click | 35.0 +/- 3.5 | 55* | 40 | 35 | NR* | 25 |

NR=No response at maximum test level (90 dB); *=significant difference (> 2 SD above mean).

Figure 6.

Staining for bone and cartilage reveals abnormalities of the otic capsule and ossicles in mature and developing small Dusp6-deficient animals. (A, B) Lateral views of left temporal bones of control (A) and small heterozygous hearing impaired (B) P22 animals. The shape of the opening to the middle ear cavity is emphasized with a black line and an abnormal notch in the heterozygote is indicated with an arrow. (C, D) Lateral views of left ears of P0 control (C) and small heterozygous (D) P0 animals are shown with some of the cochlea dissected away to enable better visualization of the ossicles. The malleus (m) and stapes (s) and incus (i) are indicated. (E, F) Lateral views of right inner ears of P5 wild type (E) and small Dusp6L/L (F) pups. Black arrow in E indicates a normal dorsal otic capsule, and grey arrow in F indicates failure of the corresponding region of the mutant otic capsule to form Alican blue-positive cartilage. (G, H) Right ossicles dissected from P5 wild type (G) and small Dusp6L/L (H) pups. All three mutant ossicles have regions in which cartilage (blue) is missing or weakly staining. (I, J) Lateral views of left temporal bones from wild type (I) and small, Dusp6L/L (J) P10 pups. Black arrow in I indicates normal development of the dorsal otic capsule, whereas grey arrow in J indicates that the corresponding region of the mutant capsule has failed to form Alizarin red-positive bone. (K, L) Left middle ears from wild type (K) and small Dusp6L/L (L) P10 pups. The mutant malleus (m) is malformed.

Further examination of the small homozygous or heterozygous Dusp6 mutant skeletons revealed that in comparison with wild type littermates, they had variable abnormalities of the middle ear bones and otic capsule. For example, the only small pup (a heterozygote) observed and collected at P0 lacked the left incus (Fig. 6 C,D). A small P5 homozygote lacked cartilage staining in the developing right otic capsule surrounding the semicircular canals (Fig. 6 E,F). The right ossicles of the same P5 homozygous mutant ear were missing tissue and/or stained weakly for cartilage (Fig. 6 G,H). Finally, there was a large dorsolateral hole in the left otic capsule of a small P10 homozygote (Fig. 6 I,J) and the malleus from that ear was misshapen. These data suggest that the hearing loss found in the small surviving Dusp6-deficient pups was likely to be conductive and could be caused by developmental delays and/or malformations of the middle ear components.

Discussion

To address the hypothesis that DUSP6 functions in vivo as a negative feedback regulator of MAPK signaling, we used gene targeting to disrupt mouse Dusp6. Homozygous mutant embryos showed variably penetrant increased levels of dpERK, the proposed DUSP6 substrate, in the limb bud, globally increased levels of Erm, a transcriptional target of the ERK pathway, as well as increased transcripts initiated from the Dusp6 promoter itself. Taken together, these molecular data are consistent with a pathway in which signals that activate ERK lead to increased transcription of Dusp6. The resulting DUSP6 protein then feeds back to dampen the signal by inactivating ERK.

One signal that initiates the negative feedback loop is likely to be FGF because we found that Dusp6 transcription depends on signaling through FGFR1 or FGFR2. Furthermore, we found that abrogation of Dusp6 function in mice leads to variably penetrant and expressive postnatal phenotypes that are similar to some of the features of ectopic FGF ligand expression or dominant activating mutations in FGFRs, which are major inputs into the ERK pathway (Powers et al., 2000; Tsang and Dawid, 2004; Eswarakumar et al., 2005). Beginning around P5, affected Dusp6 mutants were small, exhibited coronal craniosynostosis, middle ear and otic capsule malformations, and affected individuals that survived past P21 frequently had uni- or bilateral hearing loss.

Skeletal dwarfism manifesting in the early postnatal period is also characteristic to various extents of mice carrying Fgf2- or Fgf9-expressing transgenes (reviewed in Ornitz and Marie, 2002), and of knock-in mice carrying the Apert syndrome equivalent mutation (FGFR2S252W, Chen et al., 2003; Wang et al., 2005), and all of the characterized FGFR3 syndromic gain-of-function mutations (Brodie and Deng, 2003). In addition, osteoglophonic dysplasia, which can be caused by any of several activating mutations in FGFR1 (White et al., 2005) is characterized by short stature. In general, the more strongly activating receptor mutations lead to the strongest dwarfing phenotypes (Ornitz and Marie, 2002; Chen and Deng, 2005). This is consistent with the idea that FGF signaling limits endochondral bone growth and that inactivating mutations in negative regulators of FGF signaling, such as Spred2 (Bundschu et al., 2005) or Dusp6 lead to increases in FGF signaling and decreased bone growth. The bone histology of small Dusp6 mutants (reduced hypertrophic and ossification zones, disorganized proliferation zone) is more similar to that of mice with Fgfr3 gain-of-function mutations (e.g., Li et al., 1999) than to the Apert knock-in models, which in one case, showed a slightly reduced proliferation zone (Chen et al., 2003) and in the other, subtle irregularity of the hypertrophic zone (Wang et al., 2005). This suggests that DUSP6 is more likely to regulate signaling downstream of FGFR3 than of FGFR2 in the growth plate. It would be interesting to make similar comparisons of growth plate histology when a mouse model of osteoglophonic dysplasia is produced.

The craniosynostosis seen in Dusp6 mutants is also likely to be FGF-mediated, as similar phenotypes are seen consequent to ectopic Fgf2 expression or retroviral-mediated increases in Fgf3 and Fgf4 expression. In addition, many of the models of FGF receptor activation have more severe craniosynostoses, in some instances involving the coronal as well as the interfrontal and sagittal sutures (reviewed in Ornitz and Marie, 2002; Chen and Deng, 2005), than do affected Dusp6 mutants, in which only the coronal suture is affected. Suture formation is regulated by opposing FGF signaling pathways that control the balance of cellular proliferation (through FGFR2) and differentiation (through FGFR1) (Iseki et al., 1999). Thus, it is conceivable that Dusp6 has differential effects on the two pathways, perhaps regulating signaling through FGFR1 rather than through FGFR2 in the developing calvarium.

No information on middle ear or otic capsule morphology or auditory status is available for any of the mouse Fgf or Fgfr gain-of-function mutations, but the common findings of hearing loss and otopathology in Apert, Pfeiffer, Crouzon and Muenke syndrome patients (Gorlin, 2004) and the mouse Dusp6 mutant phenotype suggests that these pathologies may yet be found in the mouse models as well. Apert and Pfeiffer syndromes are characterized by limb malformations (syndactyly and broad first digits, respectively, Muenke and Wilkie, 2000; Wilkie, 2005), but no such malformations were apparent in the small Dusp6 mutants. This may not be surprising as none of the mouse models for these FGFR1 and FGFR2 syndromes have limb findings, potentially reflecting slight differences in the regulation of FGF signaling between the mice and humans.

Taken together, the Dusp6 mutant phenotypes we observed do not precisely mimic any particular mouse Fgfr gain-of-function mutation, suggesting the possibility that Dusp6 is downstream of more than one FGFR, but that it does not serve as a negative feedback regulator of all FGF signaling events. Our finding that hypomorphic mutations in either Fgfr1 or Fgfr2 reduce, but do not entirely eliminate Dusp6 expression at early embryonic stages further supports this idea. Genetic interaction studies between the Dusp6 mutant allele and various Fgf or Fgfr mutations could be used to address this hypothesis and learn which specific FGF signaling events are subject to regulation by DUSP6. Indeed, our preliminary studies suggest that loss of Dusp6 exacerbates the small size and lethality of the Fgfr1P250R allele. Whether this effect is a result of changes to craniofacial or limb skeletal elements or both is currently under investigation.

The variable penetrance of the embryonic molecular and postnatal morphologic phenotypes resulting from Dusp6 loss, and the absence of discernable morphologic changes in the mutant embryos, suggest that there could be redundant ERK phosphatases that compensate to some extent for Dusp6. These may or may not be part of a negative feedback loop regulating ERK. DUSP7 and DUSP9 are both relatively ERK-specific in vitro (Dowd et al., 1998; Dickinson et al., 2002b) and their transcripts have some areas of overlap with Dusp6, particularly in the developing limb buds and branchial arches (Dickinson et al., 2002b, and data not shown). The Dusp7 mutant phenotype has not yet been reported, but mutation of the X-linked Dusp9 gene leads to failure of placental development and consequent lethality. Tetraploid rescued embryos develop normally, however (Christie et al., 2005). Thus, conditional Dusp9 (and Dusp7) alleles will have to be generated in order to assess potential redundancy with Dusp6.

Finally, the similarity between the Dusp6 mutant phenotypes and those of humans with activating FGFR mutations suggests that mutations in DUSP6 or other negative regulators of FGF signaling, such as SPROUTY, SEF, or SPRED, or indeed other DUSP genes, are good candidates for molecularly unexplained cases of FGFR-like syndromes. Furthermore, the increasing lethality of the Dusp6 mutation as the allele was backcrossed to C57Bl/6, shows that there are likely to be genes that interact with Dusp6 and suggests that genetic variation among negative regulators of FGF signaling is a potential source of modifiers of the variable expressivity of human FGFR mutations.

Acknowledgments

We are very grateful to Drs. Mario Capecchi for providing an aliquot of R1-45 ES cells and the TK1+TK2 vector, Chuxia Deng for providing mice carrying the Fgfr1α and Fgfr2ΔIgIII alleles, Charles Keller for carrying out the microCT scans, Webster Jee for assistance with the bone histology and Lisa Urness for critiquing the manuscript. Xiaofen Wang provided excellent technical assistance with mouse production, Albert Noyes generously provided the dpERK data for Figure 1C and Samantha Covington generated the plasmid bearing the Fgfr1 5′ UTR fragment. This work was supported by grants from the NIH/NIDCD: R01DC02043 and R01DC04185, from the Deafness Research Foundation, and from the Children's Health Research Center. Daryl Scott was a Primary Children's Medical Foundation Scholar.

References

- Alonso A, Sasin J, Bottini N, Friedberg I, Friedberg I, Osterman A, Godzik A, Hunter T, Dixon J, Mustelin T. Protein tyrosine phosphatases in the human genome. Cell. 2004;117:699–711. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.05.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brodie SG, Deng CX. Mouse models orthologous to FGFR3-related skeletal dysplasias. Pediatr Pathol Mol Med. 2003;22:87–103. doi: 10.1080/pdp.22.1.87.103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bundschu K, Knobeloch KP, Ullrich M, Schinke T, Amling M, Engelhardt CM, Renné T, Walter U, Schuh K. Gene disruption of Spred-2 causes dwarfism. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:28572–28580. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M503640200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bunting M, Bernstein KE, Greer JM, Capecchi MR, Thomas KR. Targeting genes for self-excision in the germ line. Genes Dev. 1999;13:1524–1528. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.12.1524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Camps M, Nichols A, Arkinstall S. Dual specificity phosphatases: a gene family for control of MAP kinase function. Faseb J. 2000;14:6–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Camps M, Nichols A, Gillieron C, Antonsson B, Muda M, Chabert C, Boschert U, Arkinstall S. Catalytic activation of the phosphatase MKP-3 by ERK2 mitogen-activated protein kinase. Science. 1998;280:1262–1265. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5367.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen L, Deng CX. Roles of FGF signaling in skeletal development and human genetic diseases. Front Biosci. 2005;10:1961–1976. doi: 10.2741/1671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen L, Li D, Li C, Engel A, Deng CX. A Ser250Trp substitution in mouse fibroblast growth factor receptor 2 (Fgfr2) results in craniosynostosis. Bone. 2003;33:169–178. doi: 10.1016/s8756-3282(03)00222-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Z, Gibson TB, Robinson F, Silvestro L, Pearson G, Xu B, Wright A, Vanderbilt C, Cobb MH. MAP kinases. Chem Rev. 2001;101:2449–2476. doi: 10.1021/cr000241p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christie GR, Williams DJ, MacIsaac F, Dickinson RJ, Rosewell I, Keyse SM. The dual-specificity protein phosphatase DUSP9/MKP-4 is essential for placental function but is not required for normal embryonic development. Mol Cell Biol. 2005;25:8323–8333. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.18.8323-8333.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen JMM. FGFs/FGFRs and associated disorders. In: Epstein CJ, Erickson JD, Wynshaw-Boris A, editors. Inborn Errors of Development. New York: Oxford University Press; 2004. pp. 380–400. [Google Scholar]

- Corson LB, Yamanaka Y, Lai KM, Rossant J. Spatial and temporal patterns of ERK signaling during mouse embryogenesis. Development. 2003;130:4527–4537. doi: 10.1242/dev.00669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickinson RJ, Eblaghie MC, Keyse SM, Morriss-Kay GM. Expression of the ERK-specific MAP kinase phosphatase PYST1/MKP3 in mouse embryos during morphogenesis and early organogenesis. Mech Dev. 2002a;113:193–196. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4773(02)00024-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickinson RJ, Williams DJ, Slack DN, Williamson J, Seternes OM, Keyse SM. Characterization of a murine gene encoding a developmentally regulated cytoplasmic dual-specificity mitogen-activated protein kinase phosphatase. Biochem J. 2002b;364:145–155. doi: 10.1042/bj3640145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dowd S, Sneddon AA, Keyse SM. Isolation of the human genes encoding the Pyst1 and Pyst2 phosphatases: characterisation of Pyst2 as a cytosolic dual-specificity MAP kinase phosphatase and its catalytic activation by both MAP and SAP kinases. J Cell Sci. 1998;111(Pt 22):3389–3399. doi: 10.1242/jcs.111.22.3389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eblaghie MC, Lunn JS, Dickinson RJ, Münsterberg AE, Sanz-Ezquerro JJ, Farrell ER, Mathers J, Keyse SM, Storey K, Tickle C. Negative feedback regulation of FGF signaling levels by Pyst1/MKP3 in chick embryos. Curr Biol. 2003;13:1009–1018. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(03)00381-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Echevarria D, Martinez S, Marques S, Lucas-Teixeira V, Belo JA. Mkp3 is a negative feedback modulator of Fgf8 signaling in the mammalian isthmic organizer. Dev Biol. 2005;277:114–128. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2004.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eswarakumar VP, Lax I, Schlessinger J. Cellular signaling by fibroblast growth factor receptors. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2005;16:139–149. doi: 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2005.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Firnberg N, Neubüser A. FGF signaling regulates expression of Tbx2, Erm, Pea3, and Pax3 in the early nasal region. Dev Biol. 2002;247:237–250. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2002.0696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorlin RJ. Genetic Hearing Loss Associated with Musculoskeltal Disorders. In: Toriello HV, Reardon W, Gorlin RJ, editors. Hereditary Hearing Loss and Its Syndromes. New York: Oxford University Press; 2004. pp. 166–266. [Google Scholar]

- Groom LA, Sneddon AA, Alessi DR, Dowd S, Keyse SM. Differential regulation of the MAP, SAP and RK/p38 kinases by Pyst1, a novel cytosolic dual-specificity phosphatase. EMBO J. 1996;15:3621–3632. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gómez AR, López-Varea A, Molnar C, de la Calle-Mustienes E, Ruiz-Gómez M, Gómez-Skarmeta JL, de Celis JF. Conserved cross-interactions in Drosophila and Xenopus between Ras/MAPK signaling and the dual-specificity phosphatase MKP3. Dev Dyn. 2005;232:695–708. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.20227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henrique D, Adam J, Myat A, Chitnis A, Lewis J, Ish-Horowicz D. Expression of a Delta homologue in prospective neurons in the chick. Nature. 1995;375:787–790. doi: 10.1038/375787a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iseki S, Wilkie AO, Morriss-Kay GM. Fgfr1 and Fgfr2 have distinct differentiation- and proliferation-related roles in the developing mouse skull vault. Development. 1999;126:5611–5620. doi: 10.1242/dev.126.24.5611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Itoh N, Ornitz DM. Evolution of the Fgf and Fgfr gene families. Trends Genet. 2004;20:563–569. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2004.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jee WSS, Li XJ, Inoue J, Jee KW, Haba T, Ke HZ, Setterberg RB, Ma YF. Histomorphometric assay of the growing bone. In: Takahashi HE, editor. Handbook of bone morphology. Niigata, Japan: Nishimura; 1997. pp. 87–112. [Google Scholar]

- Kawakami Y, Rodriguez-León J, Koth CM, Büscher D, Itoh T, Raya A, Ng JK, Esteban CR, Takahashi S, Henrique D, et al. MKP3 mediates the cellular response to FGF8 signalling in the vertebrate limb. Nat Cell Biol. 2003;5:513–519. doi: 10.1038/ncb989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keller C, Arenkiel BR, Coffin CM, El-Bardeesy N, DePinho RA, Capecchi MR. Alveolar rhabdomyosarcomas in conditional Pax3:Fkhr mice: cooperativity of Ink4a/ARF and Trp53 loss of function. Genes Dev. 2004;18:2614–2626. doi: 10.1101/gad.1244004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keyse SM. Protein phosphatases and the regulation of mitogen-activated protein kinase signalling. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2000;12:186–192. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(99)00075-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khillan JS, Bao Y. Preparation of animals with a high degree of chimerism by one-step coculture of embryonic stem cells and preimplantation embryos. Biotechniques. 1997;22:544–549. doi: 10.2144/97223rr06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klock A, Herrmann BG. Cloning and expression of the mouse dual-specificity mitogen-activated protein (MAP) kinase phosphatase Mkp3 during mouse embryogenesis. Mech Dev. 2002;116:243–247. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4773(02)00153-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ladher RK, Wright TJ, Moon AM, Mansour SL, Schoenwolf GC. FGF8 initiates inner ear induction in chick and mouse. Genes Dev. 2005;19:603–613. doi: 10.1101/gad.1273605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li C, Chen L, Iwata T, Kitagawa M, Fu XY, Deng CX. A Lys644Glu substitution in fibroblast growth factor receptor 3 (FGFR3) causes dwarfism in mice by activation of STATs and ink4 cell cycle inhibitors. Hum Mol Genet. 1999;8:35–44. doi: 10.1093/hmg/8.1.35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y, Jiang H, Crawford HC, Hogan BL. Role for ETS domain transcription factors Pea3/Erm in mouse lung development. Dev Biol. 2003;261:10–24. doi: 10.1016/s0012-1606(03)00359-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mansour SL, Goddard JM, Capecchi MR. Mice homozygous for a targeted disruption of the proto-oncogene int-2 have developmental defects in the tail and inner ear. Development. 1993;117:13–28. doi: 10.1242/dev.117.1.13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin-Blanco E, Gampel A, Ring J, Virdee K, Kirov N, Tolkovsky AM, Martinez-Arias A. puckered encodes a phosphatase that mediates a feedback loop regulating JNK activity during dorsal closure in Drosophila. Genes Dev. 1998;12:557–570. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.4.557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mourey RJ, Vega QC, Campbell JS, Wenderoth MP, Hauschka SD, Krebs EG, Dixon JE. A novel cytoplasmic dual specificity protein tyrosine phosphatase implicated in muscle and neuronal differentiation. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:3795–3802. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.7.3795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muda M, Boschert U, Dickinson R, Martinou JC, Martinou I, Camps M, Schlegel W, Arkinstall S. MKP-3, a novel cytosolic protein-tyrosine phosphatase that exemplifies a new class of mitogen-activated protein kinase phosphatase. J Biol Chem. 1996a;271:4319–4326. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.8.4319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muda M, Theodosiou A, Rodrigues N, Boschert U, Camps M, Gillieron C, Davies K, Ashworth A, Arkinstall S. The dual specificity phosphatases M3/6 and MKP-3 are highly selective for inactivation of distinct mitogen-activated protein kinases. J Biol Chem. 1996b;271:27205–27208. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.44.27205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muenke M, Wilkie AOM. Craniosynostosis Syndromes. In: Scriver CR, Beaudet AL, Valle D, Sly WS, editors. The Metabolic and Molecular Bases of Inherited Disease. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2000. pp. 6117–6146. [Google Scholar]

- Ornitz DM, Marie PJ. FGF signaling pathways in endochondral and intramembranous bone development and human genetic disease. Genes Dev. 2002;16:1446–1465. doi: 10.1101/gad.990702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powers CJ, McLeskey SW, Wellstein A. Fibroblast growth factors, their receptors and signaling. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2000;7:165–197. doi: 10.1677/erc.0.0070165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raible F, Brand M. Tight transcriptional control of the ETS domain factors Erm and Pea3 by Fgf signaling during early zebrafish development. Mech Dev. 2001;107:105–117. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4773(01)00456-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roehl H, Nüsslein-Volhard C. Zebrafish pea3 and erm are general targets of FGF8 signaling. Curr Biol. 2001;11:503–507. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(01)00143-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith TG, Sweetman D, Patterson M, Keyse SM, Münsterberg A. Feedback interactions between MKP3 and ERK MAP kinase control scleraxis expression and the specification of rib progenitors in the developing chick somite. Development. 2005;132:1305–1314. doi: 10.1242/dev.01699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Theodosiou A, Ashworth A. MAP kinase phosphatases. Genome Biol. 2002;3 doi: 10.1186/gb-2002-3-7-reviews3009. REVIEWS3009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thisse B, Thisse C. Functions and regulations of fibroblast growth factor signaling during embryonic development. Dev Biol. 2005;287:390–402. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2005.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsang M, Dawid IB. Promotion and attenuation of FGF signaling through the Ras-MAPK pathway. Sci STKE. 2004;2004:pe17. doi: 10.1126/stke.2282004pe17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsang M, Maegawa S, Kiang A, Habas R, Weinberg E, Dawid IB. A role for MKP3 in axial patterning of the zebrafish embryo. Development. 2004;131:2769–2779. doi: 10.1242/dev.01157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vieira C, Martinez S. Experimental study of MAP kinase phosphatase-3 (Mkp3) expression in the chick neural tube in relation to Fgf8 activity. Brain Res Brain Res Rev. 2005;49:158–166. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresrev.2004.12.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Xiao R, Yang F, Karim BO, Iacovelli AJ, Cai J, Lerner CP, Richtsmeier JT, Leszl JM, Hill CA, et al. Abnormalities in cartilage and bone development in the Apert syndrome FGFR2(+/S252W) mouse. Development. 2005;132:3537–3548. doi: 10.1242/dev.01914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White KE, Cabral JM, Davis SI, Fishburn T, Evans WE, Ichikawa S, Fields J, Yu X, Shaw NJ, McLellan NJ, et al. Mutations that cause osteoglophonic dysplasia define novel roles for FGFR1 in bone elongation. Am J Hum Genet. 2005;76:361–367. doi: 10.1086/427956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkie AO. Bad bones, absent smell, selfish testes: the pleiotropic consequences of human FGF receptor mutations. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2005;16:187–203. doi: 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2005.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright TJ, Mansour SL. Fgf3 and Fgf10 are required for mouse otic placode induction. Development. 2003;130:3379–3390. doi: 10.1242/dev.00555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright TJ, Hatch EP, Karabagli H, Karabagli P, Schoenwolf GC, Mansour SL. Expression of mouse fibroblast growth factor and fibroblast growth factor receptor genes during early inner ear development. Dev Dyn. 2003;228:267–272. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.10362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu X, Li C, Takahashi K, Slavkin HC, Shum L, Deng CX. Murine fibroblast growth factor receptor 1alpha isoforms mediate node regression and are essential for posterior mesoderm development. Dev Biol. 1999;208:293–306. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1999.9227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu X, Weinstein M, Li C, Naski M, Cohen RI, Ornitz DM, Leder P, Deng C. Fibroblast growth factor receptor 2 (FGFR2)-mediated reciprocal regulation loop between FGF8 and FGF10 is essential for limb induction. Development. 1998;125:753–765. doi: 10.1242/dev.125.4.753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang W, Musci TS, Mansour SL. Trapping genes expressed in the developing mouse inner ear. Hear Res. 1997;114:53–61. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5955(97)00146-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang W, Li C, Mansour SL. Impaired motor coordination in mice that lack punc. Mol Cell Biol. 2001;21:6031–6043. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.17.6031-6043.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhan XL, Deschenes RJ, Guan KL. Differential regulation of FUS3 MAP kinase by tyrosine-specific phosphatases PTP2/PTP3 and dual-specificity phosphatase MSG5 in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genes Dev. 1997;11:1690–1702. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.13.1690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng QY, Johnson KR, Erway LC. Assessment of hearing in 80 inbred strains of mice by ABR threshold analyses. Hear Res. 1999;130:94–107. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5955(99)00003-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou B, Wu L, Shen K, Zhang J, Lawrence DS, Zhang ZY. Multiple regions of MAP kinase phosphatase 3 are involved in its recognition and activation by ERK2. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:6506–6515. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M009753200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou YX, Xu X, Chen L, Li C, Brodie SG, Deng CX. A Pro250Arg substitution in mouse Fgfr1 causes increased expression of Cbfa1 and premature fusion of calvarial sutures. Hum Mol Genet. 2000;9:2001–2008. doi: 10.1093/hmg/9.13.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]