Abstract

Combining immunotherapy with targeted therapy blocking oncogenic BRAFV600 may result in improved treatments for advanced melanoma. Here, we developed a BRAFV600E-driven murine model of melanoma, SM1, which is syngeneic to fully immunocompetent mice. SM1 cells exposed to the BRAF inhibitor vemurafenib (PLX4032) showed partial in vitro and in vivo sensitivity resulting from the inhibition of MAPK pathway signaling. Combined treatment of vemurafenib plus adoptive cell transfer (ACT) therapy with lymphocytes genetically modified with a T cell receptor (TCR) recognizing chicken ovalbumin (OVA) expressed by SM1-OVA tumors, or pmel-1 TCR transgenic lymphocytes recognizing gp100 endogenously expressed by SM1, resulted in superior antitumor responses compared with either therapy alone. T cell analysis demonstrated that vemurafenib did not significantly alter the expansion, distribution, or tumor accumulation of the adoptively transferred cells. However, vemurafenib paradoxically increased MAPK signaling, in vivo cytotoxic activity, and intratumoral cytokine secretion by adoptively transferred cells. Together, our findings, derived from two independent models combining BRAF-targeted therapy with immunotherapy, support the testing of this therapeutic combination in patients with BRAFV600 mutant metastatic melanoma.

Introduction

Targeted therapies that block driver oncogenic mutations in BRAFV600 result in unprecedentedly high response rates and improved overall survival in patients with advanced melanoma (1–4). However, these responses are usually of limited durability, which is a common feature of most oncogene-targeted therapies for cancer. Conversely, many tumor immunotherapy strategies induce low frequency but extremely durable tumor responses, frequently lasting years (5–7). The ability to combine both treatment approaches could merge the benefits of high response rates with targeted therapies and durable response rates with immunotherapies.

Combining immunotherapy with BRAF inhibitors like vemurafenib (formerly PLX4032 or RG7204) or dabrafenib (formerly GSK2118436), two highly active agents for the treatment of BRAFV600 mutant melanoma, is supported by conceptual advantages and emerging experiences (8–10) that warrant the testing of such combinations in animal models. It has been reported that BRAF inhibitors may synergize with tumor immunotherapy by the increased expression of melanosomal tumor associated antigens upon mitogen activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathway inhibition (8). There are also potential theoretical limitations to such a combination, since blocking signaling through the MAPK pathway may alter lymphocyte activation or effector functions. However, when tested at a wide range of concentrations in vitro and in vivo, BRAF inhibitors do not have significant adverse effects on human T lymphocyte functions (9, 11), and patients treated with BRAF inhibitors have increased intratumoral infiltrates by CD8+ T cells soon after therapy (10). Furthermore, RAF inhibitors can have a paradoxical effect of activating the MAPK pathway through the transactivation of CRAF by a partially blocked wild type CRAF-BRAF dimmer (12–14). This phenomenon of paradoxical MAPK activation is the molecular basis for the development of cutaneous squamous cell carcinomas in patients treated with BRAF inhibitors (15), and it could be evident in activated T cells since upstream activation of TCRs has a potent effect of activating RAS-GTP leading to enhanced CRAF-BRAF dimerization.

Previously, no implantable syngeneic BRAFV600E-driven murine melanoma model able to grow progressively in a fully immunocompetent and widely used mouse strain had been described. We derived such a cell line from mice transgenic for the BRAFV600E mutation with restricted expression in melanocytes, resulting in a murine melanoma model syngeneic to C57BL/6 mice. This model allowed us to test the concept of immunosensitization (16) by combining the vemurafenib-induced inhibition of driver oncogenic BRAFV600E signaling with adoptive cell transfer (ACT) immunotherapy. Vemurafenib meets most of the criteria as an immune sensitizing agent (16). In humans it selectively inhibits a driver oncogene in cancer cells (17), which is neither present nor required for the function of lymphocytes (9). It results in rapid melanoma cell death in humans as evidenced by a high frequency of early tumor responses in patients (1, 18). The antitumor activity may increase the expression of tumor antigens directly by tumor cells (8), or enhance the cross-presentation of tumor antigens from dying cells to antigen-presenting cells. In addition, the profound and selective antitumor effects of vemurafenib against BRAFV600 mutant melanoma cells may result in a more permissive tumor microenvironment allowing for an improved effector function of CTLs, which may be further enhanced by a direct effect of paradoxical MAPK activation. Using two different TCR transgenic cell ACT models we tested the concept of immunosensitization with vemurafenib, demonstrating an improvement of the antitumor effects using the combination over either single agent therapy alone.

Materials and Methods

Mice, Cell Lines and Reagents

Breeding pairs of C57BL/6 (Thy1.2, Jackson Laboratories, Bar Harbor, ME), pmel-1 (Thy1.1) transgenic mice (kind gift from Dr. Nicholas Restifo, Surgery Branch, National Cancer Institute, Bethesda, MD), NOD/SCID/γ chainnull (NSG) mice (NOD.Cg-PrkdcscidIl2rgtm1Wjl/SzJ, Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, ME), and mice transgenic for BRAFV600E mutation expression in melanocytes (kind gift from Drs. Philip Hinds and Frank Haluska, Tufts Medical Center, Boston, MA), were bred and kept under defined-flora pathogen-free conditions at the AALAC-approved animal facility of the Division of Experimental Radiation Oncology, UCLA, and used under the UCLA Animal Research Committee protocol #2004-159. The SM1 murine melanoma was generated from a spontaneously arising tumor in BRAFV600E mutant transgenic mice. The tumor was minced and first implanted into NSG mice, and then serially implanted into C57BL/6 mice for in vivo experiments. Part of the minced tumor was plated under tissue culture conditions for deriving the SM1 cell line. When used in vitro, SM1 was maintained in RPMI (Mediatech, Herndon, VA) with 10% FCS (Omega Scientific, Tarzana, CA), 2 mM L-glutamine (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) and 1% (v/v) penicillin, streptomycin and amphotericin (Omega Scientific). Sequencing for BRAFV600E mutation was performed as previously described (19). SM1-OVA was generated by stable expression of OVA through lentiviral transduction as previously described (20). A plasmid expressing the two chains of an MHC I restricted TCR specific for OVA (OT-1) was a kind gift of David Baltimore (California Institute of Technology, Pasadena, CA) (21). The plasmid was recloned to express a F2A picornavirus sequence between the TCR chains for high expression upon transduction of murine splenocytes using a murine stem cell virus (MSCV) retroviral vector as previously described (22, 23). M202, M229 and M233 are previously described human melanoma cell lines (19). Vemurafenib (also known as PLX4032, RG7204 or RO5185426) was obtained under a materials transfer agreement (MTA) with Plexxikon Inc. (Berkeley, CA). Vemurafenib was dissolved in dimetylsulfoxic (DMSO, Fisher Scientific, Morristown, NJ) and used for in vitro studies as previously described (19). For in vivo studies, vemurafenib was dissolved in DMSO, followed by PBS (100 µL), which was then injected daily intraperitoneally into mice at 10 mg/kg. Since the original formulation of vemurafenib is poorly bioavailable (1, 15) we used an i.p. dosing regimen that has been demonstrated to have adequate pharmacokinetic parameters in blood (24).

SM1 Oncogenic Analysis

BRAFV600E sequencing was performed as previously described (19). Copy number analysis was performed using a mouse high-density genotyping array (The Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, Maine) and data was genotyped with the R MouseDivGeno (v1.03) software package (25). To detect regions of copy number alteration, we chose the subset of “chippable” invariant genomic probes (ie, exon 1 probes) (25). Normalized and log2 transformed data was segmented using circular binary segmentation algorithm in the R DNAcopy package (26). The minimum number of markers for a changed segment was set at 5, with a 0.0005 significance level to accept a change-point. The segmented data was visualized in the Integrative Genomics Viewer (27). For comparison to human melanoma, we compared this data to copy number alterations observed in 108 human melanoma short-term cultures and cell lines (28).

Cell Viability Assays

Murine and human melanoma cells, naïve C57BL/6 splenocytes or activated pmel-1 splenocytes were seeded in 96-well flat-bottom plates (5 × 103 cells/well) with 100 µL of 10% FCS media and incubated for 24 hours. Graded dilutions of vemurafenib or DMSO vehicle control, in culture medium, were added to each well in triplicate and analyzed following the MTS assay (Promega, Madison, WI).

Adoptive Cell Transfer (ACT) Therapy In Vivo Models

For the OVA model, SM1-OVA tumors were implanted s.c. in C57BL/6 mice. When tumors reached 5–8 mm in diameter, mice were conditioned for ACT with a lymphodepleting regimen of 500 cGy of total body irradiation (TBI) and then received 1 × 106 C57BL/6-derived splenocytes intranveously (i.v.) that had been genetically modified to express the OT-1 TCR by retroviral transduction as previously described (22, 23). For the pmel-1 model, C57BL/6 mice with previously implanted SM1 tumors were treated with lymphodepleting TBI, i.v. injection of 1 × 106 gp10025–33 peptide-activated pmel-1 splenocytes and subcutaneous vaccination with gp10025–33 peptide-pulsed dendritic cells (DC) when tumors reached 5–8 mm in diameter as previously described (29, 30). In both cases, the ACT was followed by three days of daily i.p. administration of 50,000 IU of IL-2. Tumors were followed by caliper measurements three times per week.

Flow Cytometry Analysis

SM1 tumors harvested from mice were digested with collagenase and DNase (Sigma-Aldrich). Splenocytes and tumor infiltrating lymphocytes (TIL), obtained from digested SM1 tumors were stained with antibodies to CD8α (CalTag, Carlsbad, CA), CD3, CD4, Thy1.1 (BD Biosciences), OVA/H-2Kb tetramer or gp10025–33/H-2Db tetramer (Beckman Coulter), and analyzed with a LSR-II or FACSCalibur flow cytometers (BD Biosciences), followed by Flow-Jo software (Tree-Star, Ashland, OR) analysis as previously described (30). Intracellular interferon gamma (IFN-γ) staining was done as previously described (30).

Immunofluorescence Imaging

Staining was performed as previously described (23). Briefly, sections of OCT (Sakura Finetek, Torrance, CA) cryopreserved tissues were blocked in donkey serum/ PBS and incubated with primary antibodies to CD8 or Thy1.1 (BD Biosciences), followed by secondary donkey anti-rat antibodies conjugated to DyLight 488 (Jackson Immunoresearch Laboratories, West Grove, PA) or streptavidin conjugated FITC (Invitrogen). Negative controls consisted of isotype matched rabbit or rat IgG in lieu of the primary antibodies listed above. DAPI (4,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole) was used for the visualization of nuclei. Immunofluorescence images were taken in a fluorescence microscope (Axioplan-2; Carl Zeiss Microimaging, Thornwood, NY).

In Vivo Cytotoxicity Assay

The assay was performed as previously described (30). In brief, splenocytes from naïve wild type C57BL/6 mice were pulsed with 50 µg/ml of gp10025–33 peptide or the same amount of control OVA257–264 peptide. After one hour incubation, gp10025–33-pulsed wild type splenocytes were labeled with 6 nM CFSE for 10 minutes at 37°C, while control OVA257–264-pulsed splenocytes were differentially labeled with a 10-fold dilution of CFSE (0.6 nM). Cells were injected i.v. into experimental mice at 16 days after pmel-1 adoptive cell transfer. After ten hours, three mice per group were sacrificed and their spleens examined for the presence of CFSE-labeled cells. Percent cytotoxic activity was calculated as number of live gp10025–33 pulsed splenocytes divided by the number of live OVA257–264 pulsed splenocytes, which were distinguished based on the 10-fold difference in CSFE fluorescence by flow cytometry.

Bioluminescence imaging (BLI)

Pmel-1 splenocytes were retrovirally-transduced to express firefly luciferase as previously described (29), and used for ACT. BLI was performed with a Xenogen IVIS 200 Imaging System (Xenogen/Caliper Life Sciences, Hopkinton, MA) as previously described (22, 23).

Micro-PET/computed tomography imaging

Mice were anesthetized with 2% isoflurane. PET was performed one hour after intravenous administration of 200 µCi of [18F]FDG, [18F]D-FAC or [18F]FHBG and mice were scanned using a FOCUS 220 micro-PET scanner (Siemens, Knoxville, TN) (energy window of 350–750 keV and timing window of 6 ns) as previously described (23).

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed with GraphPad Prism (version 5) software (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA). A Mann-Whitney test or ANOVA with Bonferroni post-test was used to analyze experimental data. Survival curves were generated by actuarial Kaplan-Meier method and analyzed with the Jump-In software (SAS, Cary, NC) with log-rank test for comparisons from the time from tumor challenge to when mice were sacrificed due to tumors reaching 14 mm in maximum diameter, or the end of the study period had been reached.

Results

Derivation of a BRAFV600E mutated murine melanoma syngeneic to C57BL/6 mice

The cell line SM1 was derived from a spontaneously arising melanoma from a mouse with the BRAFV600E oncogene specifically expressed by melanocytes. These mice had been generated by germline insertion of the BRAFV600E gene downstream of the murine tyrosinase locus control region (promoter enhancer) as described (31). These melanocytes-specific BRAFV600E transgenic mice had been backcrossed for over 20 generations with C57BL/6 mice. It has been previously described that mice carrying transgenic BRAFV600E develop melanocytic hyperplasia histologically reminiscent of human nevi, and develop spontaneous melanomas with low penetrance due to the dominant oncogenic senescence effect of BRAFV600E (31). Cross-breading them with CDKN2A or p53 deficient mice increases the frequency of melanoma development (31), but we found that the resulting tumors could not be grown in C57BL/6 mice (data not shown) likely due to innate responses against mixed background minor antigens from the two transgenic strains. To optimize the chances of establishing a progressively growing tumor, we first passaged the original SM1 cells in deeply immune deficient NSG mice, and from there we were able to implant and develop progressively growing tumors in fully immunocompetent C57BL/6 mice.

SM1 is a vemurafenib-moderately sensitive BRAFV600E mutant melanoma

Sequencing of the hotspot T1799A mutation in BRAF demonstrated the presence of the BRAFV600E transversion in SM1 cells (Figure 1a). Whole genome copy number analysis demonstrated multiple genomic aberrations in SM1, with frequent deletions and amplifications (Supplemental Figure 1a), which is a common finding in human melanomas. Among target genes of interest, SM1 has deletion of CDKN2A and amplification of BRAF and MITF genes (Supplemental Figure 1b), events which are also frequently observed in human melanoma (Supplemental Figure 1c). We tested the antitumor effects of single agent vemurafenib against SM1 by in vitro MTS cell proliferation assay after 72 hours of treatment. The 50% inhibition concentration (IC50) of vemurafenib was 14 µM, which is approximately one log higher than the sensitivity of M229 (IC50 of 0.5 µM), a BRAFV600E mutant human melanoma cell line highly sensitive to vemurafenib, and at a similar range as the relatively resistant BRAFV600E mutant human melanoma cell line M233 (IC50 of 15 µM). SM1 was more sensitive to vemurafenib than the NRASQ61L mutant (and BRAF wild type) M202 and M207 cell lines (IC50 > 200 µM, Figure 1b). Despite its relative resistance in MTS assays, SM1 responded to vemurafenib in vitro as demonstrated by a profound G1 arrest effect (Figure 1c), and evidence of apoptotic cell death with increasing concentrations (Figure 1d). Furthermore, the exposure of SM1 to vemurafenib resulted in the expected effects of inhibiting downstream MAPK pathway signaling with additional inhibition of the PI3K/AKT signaling (Figure 1e), similar to previously described in BRAFV600E mutant human melanoma cell lines (19, 32). SM1 tumors established subcutaneously in C57BL/6 mice responded to single agent vemurafenib with a growth delay compared to the progressive tumor growth in mice treated with vehicle control (Figure 1f). As with our prior results testing human lymphocytes (9), increasing concentrations of vemurafenib did not negatively alter the viability of murine lymphocytes (Figure 2a). Furthermore, analysis for pERK demonstrated paradoxical MAPK activation, demonstrated by increase in pERK most notably at 1 and 5 µM, when murine splenocytes were exposed to vemurafenib and assayed 24 hours later (Figure 2b). Since the response to single agent vemurafenib was not complete and this BRAF inhibitor did not negatively affect murine splenocytes, we reasoned that SM1 would be a useful model to test the potential beneficial effects of adding an immunotherapy strategy to the treatment with vemurafenib.

Figure 1.

Effects of vemurafenib in the murine SM1 BRAFV600E mutant melanoma cell line. A) Detection of BRAFV600E mutation (T1799A) in SM1 by DNA sequencing. B) Human melanoma cell-lines and murine SM1 melanoma cells were exposed to increasing concentrations of vemurafenib for IC50 determination using an MTS assay. C) Cell cycle arrest in SM1 cells induced by vemurafenib (15 µM) after a 72 hour exposure analyzed by flow cytometry. D) Apoptosis marker analysis of SM1 cells exposed to vemurafenib for 72 hours at 15 µM analyzed by flow cytometry. E) Immunoblotting for analysis of signaling molecules after vemurafenib exposure of SM1 cells at increasing concentrations for 1 or 24 hours. F) SM1 tumor implanted mice were injected i.p. daily with 10 mg/kg of vemurafenib or vehicle control and followed for tumor size changes over time.

Figure 2.

A) Effects of vemurafenib on murine splenocyte viability. Cell viability assay (MTS) at different time points and doses of vemurafenib in ex vivo activated pmel-1 splenocytes. B) Immunoblotting for analysis of phosphorylated ERK (pERK) and total ERK after vemurafenib exposure of ex vivo gp-100 peptide activated pmel-1 splenocytes at increasing concentrations for 24 hours.

Combined therapy with vemurafenib and ACT immunotherapy improves antitumor responses against SM1 tumors

We generated a mouse model targeting the model tumor antigen OVA. We stably expressed OVA in SM1 cells to generate SM1-OVA for studies of ACT with splenocytes expressing a TCR specific for OVA (Figure 3a and b). Lymphodepleted C57BL/6 mice with established subcutaneously SM1-OVA tumors received ACT of splenocytes obtained from C57BL/6 mice genetically modified with a retroviral vector expressing the two chains of the OVA-specific TCR (Figure 3c and d). We titrated the conditions of this immunotherapy to provide a suboptimal antitumor activity (similar in range to single agent vemurafenib) to allow the testing of the benefits of the combination. In two replicate experiments, the combined therapy of vemurafenib and OT-1 TCR engineered splenocyte ACT was consistently superior to either therapy alone (Figure 3e), and it improved survival (Figure 3f, p = 0.0004 by log rank test).

Figure 3.

Combined antitumor activity of TCR engineered adoptive cell adoptive cell transfer (ACT) immunotherapy and vemurafenib in the ovalbumin (OVA) model. A) Schematic of the OT-1 TCR engineered ACT model based on adoptively transferring C57BL/6 splenocytes, stably transduced to express a TCR specific for OVA using retroviral transduction, into lymphodepleted mice with previously established flank SM1 cells stably expressing OVA (SM1-OVA). Vemurafenib, or DMSO vehicle control, was started on day +2 from the tumor, and on day +7 mice received the ACT of OVA-specific TCR transduced splenocytes with lymphodepleting radiation therapy the day before, followed by three days of systemic IL-2 therapy. B). Western blot analysis for OVA expression in parental SM1 cells (line 1), SM1-OVA cells (line 2) and SM1-OVA tumor graft (line 3). C) Schematic of the MSCV-based retroviral vector co-expressing the alpha and beta chains of the OT-1 TCR linked by a F2A picornavirus sequence. D) Tetramer analysis for OVA-specific surface TCR expression on splenocytes from C57BL/6 untransduced (left panel) or transduced with the OT-1 TCR-expressing retrovirus. E) Tumor growth curves in C57BL/6 mice with established SM1-OVA tumors. F) Kaplan-Meier actuarial plot of time to mouse sacrifice due to large tumor burden, or to study termination when tumor size was less than 14 mm in maximum diameter, combining results from two replicate experiments in the OVA TCR engineered ACT model.

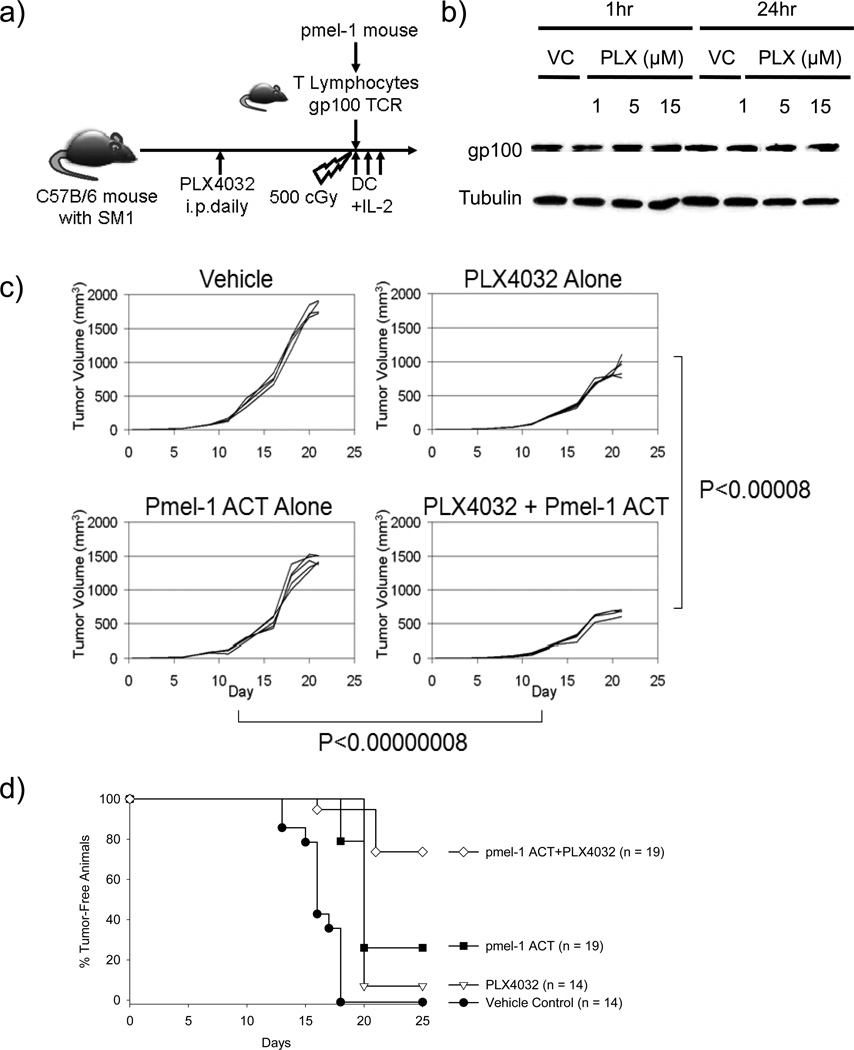

Since the OVA model is based on the recognition of a foreign antigen, we decided to confirm the results in the pmel-1 ACT model (Figure 4a). The pmel-1 model is based on T cells transgenic for a TCR recognizing the murine melanosomal antigen gp100 (33), which is endogenously expressed by SM1 (Figure 4b). In three replicate experiments, the combined therapy with pmel-1 ACT and vemurafenib provided superior antitumor activity compared to either therapy alone which had been titrated to provide a suboptimal response against established SM1 tumors (Figure 4c). As with the OVA model, Kaplan-Meier analysis of actuarial survival curves generated with the combined data from three replicate experiments demonstrated that the combined therapy improved survival compared to single therapies (Figure 4d, p < 0.0001 by log rank test).

Figure 4.

Combined antitumor activity of TCR engineered adoptive cell adoptive cell transfer (ACT) immunotherapy and vemurafenib in the pmel-1 model. A) Schematic of the pmel-1 model, where C57BL/6 mice with established SM1 tumors received vemurafenib, or DMSO vehicle control, from day +2 after tumor implantation, lymphodepleting radiation therapy on day +7 and the adoptive transfer of pmel-1 splenocytes activated in vitro with gp100 peptide on day +7. This was followed with three days of systemic IL-2 therapy and gp100 peptide pulsed dendritic cell (DC) vaccines on day +7. B). Western blot analysis for gp100 expression in parental SM1 cells exposed to DMSO vehicle control or vemurafenib (PLX4032) at three different concentrations for 1 or 24 hours. Protein loading was normalized to tubulin. C) Tumor growth curves in C57BL/6 mice with established SM1 tumors. D) Kaplan-Meier actuarial plot of time to mouse sacrifice due to large tumor burden, or to study termination when tumor size was less than 14 mm in maximum diameter, combining results from two replicate experiments in the pmel-1 ACT model.

Vemurafenib does not alter the tumor antigen or MHC expression by SM1 cells

A hypothesized mechanism of improved antitumor activity of combining BRAF targeted therapy with immunotherapy is an increase in tumor antigen or MHC expression by cancer cells (8). Therefore, we tested if exposure to vemurafenib increased the expression of the gp100 melanoma tumor antigen or the expression of surface MHC molecules, as well as the recognition by TCR transgenic cells specific for gp100. However, vemurafenib did not significantly alter gp100 tumor antigen expression by SM1 cells (Figure 4b). The baseline expression of the MHC molecule H2-Db was very low in cultured SM1 cells, and it did not significantly change upon exposure to vemurafenib (Supplemental Figure 2).

No difference in T cell number, distribution and tumor targeting of ACT therapy when combined with vemurafenib

It has been reported that biopsies of some patients treated with BRAF inhibitors have increased CD8 infiltrates (10). To analyze if vemurafenib expanded or changed the distribution of adoptively transferred cells in vivo with higher accumulation in tumors, we analyzed their presence in spleens, tumor-draining lymph nodes and tumors. However, in our model there was no evidence of either a systemic (spleen or lymph nodes) or local (tumor) increase in the quantity of adoptively transferred antitumor T cells with treatment with vemurafenib (Figure 5a and b, and Supplemental Figure 3a and b). To rule out that we were missing an effect by not analyzing the whole animal, we genetically labeled the adoptively transferred cells with the firefly luciferase transgene to allow their in vivo tracking using BLI. Again, there was no evidence of a differential expansion or in vivo distribution and tumor targeting by the adoptively transferred pmel-1 cells when mice were treated with vemurafenib (Figure 5c). The quantitative analysis of luciferase activity over time in mice treated with pmel-1 ACT alone or pmel-1 ACT combined with vemurafenib demonstrated similar in vivo distribution to lymphoid organs and to the antigen-matched tumors (Figure 5d). Furthermore, we employed a higher resolution method to visualize a differential systemic immune response using the PET probe [18F]FAC, which has preferential uptake by activated murine lymphocytes (34). Again, there was no difference in the PET scan images with or without systemic treatment with vemurafenib (Supplemental Figure 4).

Figure 5.

Effects of vemurafenib on the number or distribution of adoptively transferred lymphocytes. A) pmel-1 transgenic T cells were used for ACT in the pmel-1 combined therapy model. Tumors were harvested on day +5 after ACT and representative H&E (left panel) and immunofluorescence for pmel-1 cells stained with anti-Thy1.1-FITC (green, right panels), and nuclei stained with DAPI (blue, right panels). B) Splenocytes and tumor infiltrating lymphocytes harvested at day 5 were counted and analyzed by flow cytometry for gp100 tetramer/Thy1.1/CD3/CD8 staining. C) In vivo bioluminescence imaging of TCR transgenic T cell distribution. Pmel-1 transgenic T cells were transduced with a retrovirus-firefly luciferase and used for ACT. Representative figure at day 5 depicting three replicate mice per group. D) Quantitation of bioluminescence imaging of serial images obtained through day 14 post-ACT of pmel-1 transgenic cells expressing firefly luciferase with 3 mice per group.

Increased functional activation of intratumoral lymphocytes with exposure to vemurafenib

The in vivo cytotoxicity assay allowed testing if vemurafenib had a direct effect of enhancing lymphocyte cytotoxicity in vivo, independent of its effects on SM1 tumor cells, since the targets are syngeneic splenocytes devoid of the BRAFV600E mutation. In three replicate experiments the ACT of pmel-1 cells induced potent cytotoxic effects against splenocytes pulsed with the gp100 peptide, but not against the control OVA peptide. The cytotoxicity increased with systemic treatment with vemurafenib when analyzed at limiting numbers of adoptively transferred pmel-1 cells (Figure 6a), but not when the number of pmel-1 cells adoptively transferred was one log higher and the pmel-1 cells already had a very high lytic activity against gp100 peptide pulsed splenocytes (Supplemental Figure 5). We then analyzed the activation state of TILs by detecting cytokine production. In two replicate experiments, TIL collected from mice treated with the combination showed a higher ability to respond to short term ex vivo restimulation with the gp100 antigen, as assessed by interferon-γ secretion (Figure 6b and Supplemental Figure 6). Therefore, the addition of vemurafenib increased the functionality of adoptively transferred pmel-1 cells in terms of their ability to release an immune stimulating cytokine and intrinsic antigen-specific lytic activity.

Figure 6.

Effects of vemurafenib on the cytotoxic and cytokine producing functions of adoptively transferred lymphocytes. A) Effects on cytotoxicity with the in vivo cytotoxic T cell assay. C57BL/6 mice received ACT of 5 × 104 pmel-1 splenocytes and daily vemurafenib or vehicle administered intraperitoneally. On day 16 mice received an intravenous challenge with CFSE-labeled target cells (splenocytes pulsed with gp100 peptide or control OVA peptide). Ten hours later splenocytes were harvested and analyzed by flow cytometry. B) Effects on cytokine production upon antigen re-stimulation. SM1 tumor-bearing C57BL/6 mice received pmel-1 ACT with or without vemurafenib. At day 5 post-ACT, tumors were harvested and TILs isolated for intracellular IFN-γ staining analyzed by intracellular staining by flow cytometry upon 5 hour ex vivo exposure to the gp10025–33 peptide.

Discussion

Two approaches with high response rates for the treatment of patients with metastatic melanoma are BRAF inhibitors and lymphocyte ACT therapies with ex vivo expanded melanoma-specific T cells (1, 18, 35). However, in both cases, tumors frequently relapse after an initial response (18, 36). Our data supporting the combination of ACT with vemurafenib provides a strong rationale to translate combined immunotherapy and targeted therapy for patients with BRAFV600 mutant metastatic melanoma. The scientific rationale for combinations of targeted therapies and immunotherapy is based on the notion that pharmacological interventions with specific inhibitors of oncogenic events in cancer cells could sensitize cancer cells to immune attack, which has been termed immunosensitization (16). An immune sensitizing agent should ideally block key oncogenic events in cancer cells, resulting in an increase in cell surface ligands for immune effector cells, and induce an intracellular pro-apoptotic cancer cell milieu, which would enhance the ability of immune effector cells like CTLs and natural killer (NK) cells to recognize and kill cancer cells. At the same time, immune sensitizing agents should not impair the viability or function of immune effector cells (16). Most of these desired features could be fulfilled by specific BRAF inhibitors currently used in patients with BRAFV600 mutant metastatic melanoma (8–10).

We explored the potential mechanisms by which vemurafenib could improve the antitumor activity of adoptively transferred T cells in two animal models. Our studies demonstrate that this BRAF inhibitor does not change the cell expansion or distribution of adoptively transferred cells by morphological and molecular imaging studies. However, lymphocytes exposed to vemurafenib have higher pERK, which is a key feature of an activated MAPK signaling pathway. Furthermore, we noted an immune cell-intrinsic ability to increase the cytotoxic function of antigen-specific T cells, and TILs from vemurafenib-treated mice had higher functional activation with increased ability to release the immune stimulating cytokine IFN-γ upon antigen re-exposure. These immune activating effects of vemurafenib can be explained by the ability of RAF inhibitors to paradoxically activate the MAPK pathway in cells that are wild type for BRAF but have strong upstream signaling (12–15). Therefore, it is possible that in this model with a moderately sensitive tumor target the main beneficial effects of vemurafenib are derived from the ability of this agent to directly improve immune effector functions independent of the effects against the BRAFV600E mutant tumor.

One of the potential mechanisms of combinatorial activity of tumor-damaging agents and immunotherapy, leading to increased TIL activation, is an increased antigen presentation by the tumor cells themselves (8). However, in our studies we could not readily detect an increase in tumor antigen or MHC molecule expression by SM1 cells exposed to vemurafenib. An alternative approach leading to increased antigen presentation would be an increased tumor antigen cross-presentation by host antigen presenting cells picking up antigen released by dying cancer cells. However, it is hard to develop direct evidence of tumor antigen cross-presentation in these animal models, which may be further explored. It is also possible that vemurafenib could alter the tumor microenviroment inhibiting the production of immune suppressive factors by the melanoma cells, leading to increased adoptively transferred lymphocyte activation without increasing antigen cross-presentation. A slower tumor growth and blocking the oncogenic MAPK pathway signaling would favorably modulate the tumor microenviroment allowing antitumor lymphocytes to be better activated and produce interferon gamma as we have detected.

It is possible that the mechanism of improved combinatorial effects may be different in a BRAFV600 mutant tumor with higher sensitivity to vemurafenib. In our models based on the SM1 cell line, single agent vemurafenib had mainly an anti-proliferative effect in vivo, as opposed to the induction of rapid tumor regression. SM1 is relatively resistant to single agent vemurafenib in vitro and in vivo, likely because of the multiple genomic alterations in this cell line including deletion of CDKN2A and amplification of BRAF and MITF. In fact, amplification of BRAFV600E is a bona fide mechanism of resistance to BRAF inhibitors in the clinic (37), and likely the main reason why SM1 established tumors in mice do not regress with the treatment with vemurafenib. If new murine melanoma cell lines driven by BRAFV600E are developed in the future with higher in vitro and in vivo sensitivity to BRAF inhibitors, it is possible that even more synergistic effects of BRAF inhibitors with immunotherapy may be detected. A rapid tumor response may be more likely to induce tumor antigen-specific T cell activation by antigen cross-presentation, or inhibition of the immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment, and the responding tumor may enlist inflammatory cells producing chemokine attractants for lymphocytes, resulting in increased intratumoral infiltration.

In conclusion, combined therapy with the BRAFV600-specific inhibitor vemurafenib and TCR engineered ACT resulted in superior antitumor effects against a fully syngeineic BRAFV600E mutant melanoma. Although the absolute number of T cells infiltrating the tumor was not increased by vemurafenib, the combination increased the functionality of antigen-specific T lymphocytes. Therefore, our studies support the clinical testing of combinations of BRAF targeted therapy and immunotherapy for patients with advanced melanoma.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank Ashley Cass for assistance with bioinformatic analyses. Vemurafenib (PLX4032) was generously provided by Dr. Gideon Bollag from Plexxikon Inc. This work was funded by the NIH grants P50 CA086306 and P01 CA132681, The Seaver Institute, the Louise Belley and Richard Schnarr Fund, the Wesley Coyle Memorial Fund, the Garcia-Corsini Family Fund, the Fred L. Hartley Family Foundation, the Ruby Family Foundation, the Jonsson Cancer Center Foundation, and the Caltech-UCLA Joint Center for Translational Medicine (all to A.R.). N.A.G. was supported by the UCLA Tumor Biology Program, US Department of Health and Human Services, Ruth L. Kirschstein Institutional National Research Service Award T32 CA009056. A.M. was supported by Eugene V. Cota-Robles Fellowship and The Competitive Edge Fellowship funded by NSF AGEP. P.C.T. was supported by K08 AI091663.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: Antoni Ribas has received honoraria from consulting with Roche-Genentech, which is the maker of vemurafenib.

References

- 1.Flaherty KT, Puzanov I, Kim KB, Ribas A, McArthur GA, Sosman JA, et al. Inhibition of mutated, activated BRAF in metastatic melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:809–819. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1002011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kefford R, Arkenau H, Brown MP, Millward M, Infante JR, Long GV, et al. Phase I/II study of GSK2118436, a selective inhibitor of oncogenic mutant BRAF kinase, in patients with metastatic melanoma and other solid tumors. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2010;28:611s. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chapman PB, Hauschild A, Robert C, Haanen JB, Ascierto P, Larkin J, et al. Improved survival with vemurafenib in melanoma with BRAF V600E mutation. The New England journal of medicine. 2011;364:2507–2516. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1103782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sosman JA, Kim KB, Schuchter L, Gonzalez R, Pavlick AC, Weber JS, et al. Survival in BRAF V600-mutant advanced melanoma treated with vemurafenib. The New England journal of medicine. 2012;366:707–714. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1112302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Atkins MB, Lotze MT, Dutcher JP, Fisher RI, Weiss G, Margolin K, et al. High-dose recombinant interleukin 2 therapy for patients with metastatic melanoma: analysis of 270 patients treated between 1985 and 1993. J Clin Oncol. 1999;17:2105–2116. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1999.17.7.2105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hodi FS, O'Day SJ, McDermott DF, Weber RW, Sosman JA, Haanen JB, et al. Improved survival with ipilimumab in patients with metastatic melanoma. The New England journal of medicine. 2010;363:711–723. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1003466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Robert C, Thomas L, Bondarenko I, O'Day S, M DJ, Garbe C, et al. Ipilimumab plus dacarbazine for previously untreated metastatic melanoma. The New England journal of medicine. 2011;364:2517–2526. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1104621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Boni A, Cogdill AP, Dang P, Udayakumar D, Njauw CN, Sloss CM, et al. Selective BRAFV600E inhibition enhances T-cell recognition of melanoma without affecting lymphocyte function. Cancer research. 2010;70:5213–5219. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-0118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Comin-Anduix B, Chodon T, Sazegar H, Matsunaga D, Mock S, Jalil J, et al. The oncogenic BRAF kinase inhibitor PLX4032/RG7204 does not affect the viability or function of human lymphocytes across a wide range of concentrations. Clin Cancer Res. 2010;16:6040–6048. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-1911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wilmott JS, Long GV, Howle JR, Haydu LE, Sharma RN, Thompson JF, et al. Selective BRAF inhibitors induce marked T-cell infiltration into human metastatic melanoma. Clinical cancer research : an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research. 2012;18:1386–1394. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-2479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hong DS, Vence L, Falchook G, Radvanyi LG, Liu C, Goodman V, et al. BRAF(V600) Inhibitor GSK2118436 Targeted Inhibition of Mutant BRAF in Cancer Patients Does Not Impair Overall Immune Competency. Clinical cancer research : an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research. 2012;18:2326–2335. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-2515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Heidorn SJ, Milagre C, Whittaker S, Nourry A, Niculescu-Duvas I, Dhomen N, et al. Kinase-dead BRAF and oncogenic RAS cooperate to drive tumor progression through CRAF. Cell. 2010;140:209–221. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.12.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Poulikakos PI, Zhang C, Bollag G, Shokat KM, Rosen N. RAF inhibitors transactivate RAF dimers and ERK signalling in cells with wild-type BRAF. Nature. 2010;464:427–430. doi: 10.1038/nature08902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Halaban R, Zhang W, Bacchiocchi A, Cheng E, Parisi F, Ariyan S, et al. PLX4032, a selective BRAF(V600E) kinase inhibitor, activates the ERK pathway and enhances cell migration and proliferation of BRAF melanoma cells. Pigment Cell Melanoma Res. 2010;23:190–200. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-148X.2010.00685.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Su F, Viros A, Milagre C, Trunzer K, Bollag G, Spleiss O, et al. RAS mutations in cutaneous squamous-cell carcinomas in patients treated with BRAF inhibitors. The New England journal of medicine. 2012;366:207–215. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1105358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Begley J, Ribas A. Targeted therapies to improve tumor immunotherapy. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:4385–4391. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-4804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bollag G, Hirth P, Tsai J, Zhang J, Ibrahim PN, Cho H, et al. Clinical efficacy of a RAF inhibitor needs broad target blockade in BRAF-mutant melanoma. Nature. 2010;467:596–599. doi: 10.1038/nature09454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ribas A, Kim K, Schuchter L, Gonzalez R, Pavlick AC, Weber J, et al. BRIM-2: An Open-label, multicenter Phase II study of RG7204 (PLX4032) in previously treated patients with BRAF V600E mutation-positive metastatic melanoma. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2011;29 Abstr 8509. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sondergaard JN, Nazarian R, Wang Q, Guo D, Hsueh T, Mok S, et al. Differential sensitivity of melanoma cell lines with BRAFV600E mutation to the specific raf inhibitor PLX4032. J Transl Med. 2010;8:39. doi: 10.1186/1479-5876-8-39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Koya RC, Kasahara N, Pullarkat V, Levine AM, Stripecke R. Transduction of acute myeloid leukemia cells with third generation self-inactivating lentiviral vectors expressing CD80 and GM-CSF: effects on proliferation, differentiation, and stimulation of allogeneic and autologous anti-leukemia immune responses. Leukemia. 2002;16:1645–1654. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2402582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yang L, Baltimore D. Long-term in vivo provision of antigen-specific T cell immunity by programming hematopoietic stem cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:4518–4523. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0500600102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Brusko TM, Koya RC, Zhu S, Lee MR, Putnam AL, McClymont SA, et al. Human antigen-specific regulatory T cells generated by T cell receptor gene transfer. PLoS One. 2010;5:e11726. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0011726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Koya RC, Mok S, Comin-Anduix B, Chodon T, Radu CG, Nishimura MI, et al. Kinetic phases of distribution and tumor targeting by T cell receptor engineered lymphocytes inducing robust antitumor responses. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:14286–14291. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1008300107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lee JT, Li L, Brafford PA, van den Eijnden M, Halloran MB, Sproesser K, et al. PLX4032, a potent inhibitor of the B-Raf V600E oncogene, selectively inhibits V600E-positive melanomas. Pigment cell & melanoma research. 2010;23:820–827. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-148X.2010.00763.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yang H, Ding Y, Hutchins LN, Szatkiewicz J, Bell TA, Paigen BJ, et al. A customized and versatile high-density genotyping array for the mouse. Nature methods. 2009;6:663–666. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Olshen AB, Venkatraman ES, Lucito R, Wigler M. Circular binary segmentation for the analysis of array-based DNA copy number data. Biostatistics. 2004;5:557–572. doi: 10.1093/biostatistics/kxh008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Robinson JT, Thorvaldsdottir H, Winckler W, Guttman M, Lander ES, Getz G, et al. Integrative genomics viewer. Nature biotechnology. 2011;29:24–26. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Beroukhim R, Mermel CH, Porter D, Wei G, Raychaudhuri S, Donovan J, et al. The landscape of somatic copy-number alteration across human cancers. Nature. 2010;463:899–905. doi: 10.1038/nature08822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Prins RM, Shu CJ, Radu CG, Vo DD, Khan-Farooqi H, Soto H, et al. Anti-tumor activity and trafficking of self, tumor-specific T cells against tumors located in the brain. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2008;57:1279–1289. doi: 10.1007/s00262-008-0461-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vo DD, Prins RM, Begley JL, Donahue TR, Morris LF, Bruhn KW, et al. Enhanced antitumor activity induced by adoptive T-cell transfer and adjunctive use of the histone deacetylase inhibitor LAQ824. Cancer research. 2009;69:8693–8699. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-1456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Goel VK, Ibrahim N, Jiang G, Singhal M, Fee S, Flotte T, et al. Melanocytic nevus-like hyperplasia and melanoma in transgenic BRAFV600E mice. Oncogene. 2009;28:2289–2298. doi: 10.1038/onc.2009.95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nazarian R, Shi H, Wang Q, Kong X, Koya RC, Lee H, et al. Melanomas acquire resistance to B-RAF(V600E) inhibition by RTK or N-RAS upregulation. Nature. 2010;468:973–977. doi: 10.1038/nature09626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Overwijk WW, Theoret MR, Finkelstein SE, Surman DR, de Jong LA, Vyth-Dreese FA, et al. Tumor regression and autoimmunity after reversal of a functionally tolerant state of self-reactive CD8+ T cells. J Exp Med. 2003;198:569–580. doi: 10.1084/jem.20030590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Radu CG, Shu CJ, Nair-Gill E, Shelly SM, Barrio JR, Satyamurthy N, et al. Molecular imaging of lymphoid organs and immune activation by positron emission tomography with a new [18F]-labeled 2'-deoxycytidine analog. Nat Med. 2008;14:783–788. doi: 10.1038/nm1724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rosenberg SA, Restifo NP, Yang JC, Morgan RA, Dudley ME. Adoptive cell transfer: a clinical path to effective cancer immunotherapy. Nat Rev Cancer. 2008;8:299–308. doi: 10.1038/nrc2355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Johnson LA, Morgan RA, Dudley ME, Cassard L, Yang JC, Hughes MS, et al. Gene therapy with human and mouse T-cell receptors mediates cancer regression and targets normal tissues expressing cognate antigen. Blood. 2009;114:535–546. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-03-211714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shi H, Moriceau G, Kong X, Lee MK, Lee H, Koya RC, et al. Melanoma whole-exome sequencing identifies (V600E)B-RAF amplification-mediated acquired B-RAF inhibitor resistance. Nature communications. 2012;3:724. doi: 10.1038/ncomms1727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.