Abstract

Patients with squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck (SCCHN) have depressed antitumour immunity. The presence of CD4+CD25+ (Treg) cells in these patients might be, in part, responsible for downregulation of antitumour immune responses. To evaluate the frequency and characteristics of Treg in the peripheral circulation of patients with SCCHN, we used multicolour flow cytometry. Expression of CCR7, CD62L, ζ chain and Annexin V binding to Treg and non-Treg CD4+ lymphocyte populations were evaluated. Treg were confirmed to be Foxp3+ and GITR+. The Treg frequency was significantly elevated in patients with active disease and those with no evidence of disease (NED) following curative therapies. Both Treg and non-Treg CD4+ T cells in patients were significantly enriched in CCR7− and CD62L− cell subsets. Although Treg in patients contained a higher proportion of double negative (CCR7−CD62L−) cells, the majority of Tregs were CCR7−CD62L+. The proportion of Annexin V+CD4+ T cells was higher in patients (P<0.00005) than normal controls (NC), and Treg were significantly more sensitive to apoptosis than non-Treg in patients and NC. Expression of ζ was reduced in all subsets of CD4+ T cells obtained from patients vs NC. The data suggest that Treg in patients with SCCHN largely contain T cells with the ‘effector’ phenotype, which bind Annexin V and have low ζ expression, consistent with their activation state and a rapid turnover in the peripheral circulation.

Keywords: head and neck cancer, CD4+CD25+ T cells, regulatory T cells (Treg), CD4+ T-cell subsets

Immune tolerance to self-antigens is essential for the prevention of autoreactivity and autoimmune diseases. Currently, a subset of CD4+ T cells expressing CD25, the IL-2 receptor α-chain, and referred to as regulatory T cells (Treg), is considered to be responsible for the control of autoreactive lymphocytes (Shevach, 2000). Substantial experimental evidence supports the regulatory role of CD4+CD25+ T cells in animals and man. Thus, in rodents, depletion of Treg resulted in the development of autoimmune diseases and enhanced immune responses against alloantigens and tumour-antigens, leading to rejection of transplanted tumours by the host immune system (Shimizu et al, 1999; Sakaguchi et al, 2001; Sutmuller et al, 2001). This finding was not unexpected, as a majority of known tumour-associated antigens (TAA) are altered or overexpressed self-antigens. Therefore, CD4+CD25+ Treg are a likely candidate for downregulation of immune responses to these TAA. In man, Treg have been described to be present in increased proportions among tumour-infiltrating lymphocytes (TIL) and in the peripheral circulation of patients with various malignancies (Woo et al, 2001; Liyanage et al, 2002; Woo et al, 2002; Wolf et al, 2003). Based on phenotypic characteristics, this population of lymphocytes accounts for 5–10% of all CD4+ T cells in the peripheral circulation of healthy individuals (e.g., Wolf et al, 2003), but in patients with cancer, peripheral mononuclear cells (PBMC) may contain up to 25–30% of Treg (Woo et al, 2002).

Patients with squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck (SCCHN) have depressed antitumour immune responses, and tumour progression or recurrence is associated with particularly severe immune dysfunction (Whiteside, 2004). While several distinct mechanisms have been suggested to explain immune unresponsiveness in these patients, including the presence of tumour-derived inhibitory factors (e.g., PGE2), T-cell apoptosis, inhibitory cytokines (e.g., IL-10) or excess of suppressive macrophages, the presence of Treg at a high frequency could also contribute to lymphocyte dysfunction, which is characteristically and consistently observed in patients with SCCHN (Reichert et al, 1998; Hoffmann et al, 2002; Reichert et al, 2002).

The CD4+ T-cell subset of lymphocytes was previously studied by us in patients with SCCHN (Kuss et al, 2003; Kuss et al, 2004a). We found that the absolute count of circulating CD4+ T cells was significantly decreased in these patients (Kuss et al, 2004a). While the pool of naïve CD4+CD45RO-CD27+ T cells was significantly smaller in patients than in age-matched normal controls (NC), the pool of memory CD4+CD45RO+ T cells was significantly expanded (Kuss et al, 2003). Thus, based on the lymphocyte count, their phenotype and the T-cell receptor excision circle (TREC) analysis (Kuss et al, 2004b), it appears that the significant paucity of naïve and excess of memory CD4+ T cells characterises the subset of CD4+ T cells in SCCHN patients. However, phenotypic characteristics or distribution of CD4+CD25 Treg among these CD4+ cell subsets is not known.

In the present study, we investigated whether the circulating pool of CD4+CD25+ Treg in patients with SCCHN was expanded relative to that in NC and evaluated phenotypic and functional characterisitics of Treg. The hypothesis tested predicted that PBMC of these patients might be enriched in CD4+CD25+ Treg, which, by virtue of downregulating antitumour immune functions, could contribute to the progression or recurrence of head and neck cancer.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patients and controls

Patients with head and neck cancer (HNC) were seen at the Outpatient Otolaryngology Clinic, University of Pittsburgh Medical Center (UPMC) between February and December 2003. Blood samples were obtained from consecutive patients who signed an informed consent form approved by the Institutional Review Board. Normal healthy donors (NC), aged from 45 to 70 years, were recruited among the laboratory personnel and asked to sign the consent form prior to donating blood. The study included 24 patients with HNC and 17 NC. The clinicopathologic characteristics of the patients included in the study are shown in Table 1. The cohort included 16 male and eight female subjects aged from 46 to 84 years. All patients had histologically proven SCCHN, with six cancers originating in the larynx, nine in the oral cavity, two in the oropharynx and seven in the hypopharynx. Nine out of 24 patients had T3 or T4 disease, and 13 out of 24 had nodal metastases. At the time of the blood draw, 14 patients showed no evidence of disease (NED), having previously received curative therapies, and 10 patients had active disease (AD; presurgery).

Table 1. Clinicopathologic features of patients with SCCHN included in the study.

| n | |

|---|---|

| Age (years) mean (range) | 58 (46–84) |

| Sex | |

| Male | 16 |

| Female | 8 |

| Total | 24 |

| Tumour site | |

| Larynx | 6 |

| Oral cavity | 9 |

| Pharynx | 2 |

| Hypopharynx | 7 |

| Tumour stage | |

| T1 | 6 |

| T2 | 8 |

| T3 | 2 |

| T4 | 7 |

| TX | 1 |

| Nodal status | |

| N0 | 11 |

| N1 | 4 |

| N2 | 9 |

| Alcohol history | |

| Yes | 9 |

| No | 10 |

| Prior | 3 |

| Unknown | 2 |

| Smoking history | |

| Yes | 13 |

| No | 3 |

| Prior | 5 |

| Unknown | 3 |

| Status at day of blood draw | |

| No evidence of disease | 14 |

| Active disease (presurgery) | 10 |

SCCHN=squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck.

Cell isolation

Venous blood obtained from patients or controls (20–30 ml) was delivered to the laboratory within 2 h of phlebotomy. Peripheral mononuclear cells were isolated from venous blood by density gradient sedimentation on Ficoll-Hypaque. Cells recovered from the gradient interface were washed twice in medium, counted and immediately used for staining.

Antibodies

The following monoclonal antibodies (mAbs): anti-CD3-ECD (UCHT1), anti-CD4-PE (13B8.2), anti-CD8-PC5 (SFCI21Thy2D3), anti-CD25-PC5 (B1.49.9), anti-CD62L-ECD (DREG56) and the respective isotypes used as negative controls for surface staining were all purchased from Beckmann Coulter (Miami, FL, USA). Anti-CCR7-FITC mAb was purchased from R&D Systems Inc., Minneapolis, MN USA. For intracellular detection of TCR ζ chain, anti-CD247-FITC (6B10.2) obtained from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc., CA, USA was used. Unlabelled polyclonal anti-Foxp3 Abs and the secondary labelled Abs were purchased from Abcam, Ltd., Cambridge, MA, USA. Carboxyfluorescein-conjugated mAb to glucocorticoid-induced TNF receptor (GITR) was purchased from R & D Systems.

Annexin V apoptosis detection kit

The Annexin V-FITC Apoptosis Detection Kit was purchased from BD PharMingen and used as recommended by the manufacturer.

Cell staining

Cells were resuspended in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), containing 0.1% BSA and 0.1% NaN3 to the final concentration of 2 × 106 ml−1. Cells were stained for flow cytometry as previously described (Kuss et al, 2003). Briefly, optimal working dilutions of all Abs used for staining were first determined by titrations with normal PBMC. Checkerboard titrations were used to determine optimal dilutions of primary and secondary Abs used for indirect staining (Foxp3). For surface staining, PBMC were incubated with the optimal dilution of each mAb for 25 min at 4°C in the dark, washed twice with PBS containing 0.1% (w v−1) bovine serum albumin (BSA) and 0.1% (w v−1) NaN3 and finally fixed by adding 2% (v v−1) paraformaldehyde (PFA) in PBS. For intracellular staining (TCR ζ chain and Foxp3), surface staining for T-cell markers was followed by two washes with the PBS/BSA/NaN3 buffer and by subsequent fixation of the PBMC in 2.5% PFA for 10 min at room temperature in the dark. After another wash with the same buffer, PBMC were permeabilised with saponin (0.1% v v−1 in BSA) and washed with cold saponin solution. Next, anti-ζ or anti-Foxp3 mAb or IgG1-FITC isotype was added to the cells. After incubation for 25 min at 4°C in the dark, the cell suspension was washed again with 0.1% saponin, followed by another wash with the PBS/BSA/NaN3 buffer or by a secondary Ab in the case of Foxp3. The cells were finally fixed with 2% PFA in PBS. Stained samples were immediately analysed by flow cytometry.

Flow cytometry analysis

Flow cytometry was performed on a Coulter Epics XL Flow-Cytometer. Gating strategy used to identify the Anx+PI- populations of lymphocytes was previously described (Bauernhofer et al, 2003). To identify Treg populations, the gate was set to acquire CD4+CD25high T cells. The subsequent data analysis was performed using the Coulter EXPO 32vl.2 analysis software.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using the Student's t-test, and P-values of <0.05 were considered significant.

RESULTS

Proportions of Treg in the circulation of patients with SCCHN and controls

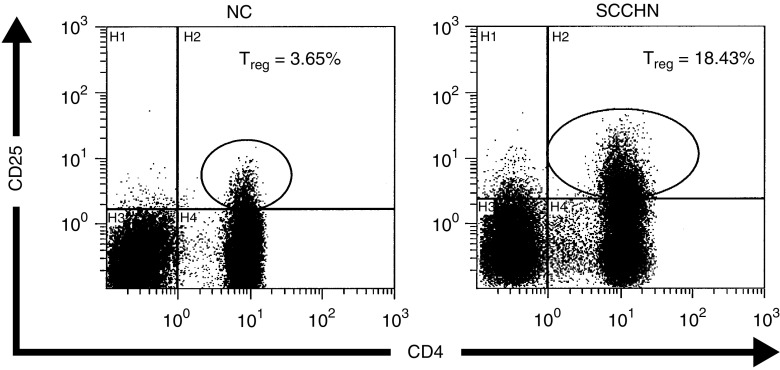

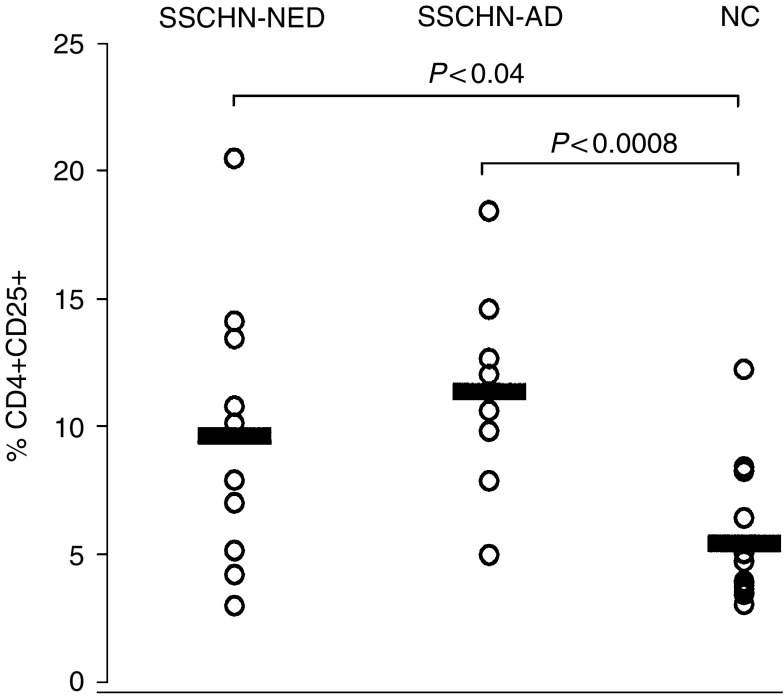

Flow cytometry analysis indicated that the patients had significantly higher percentages of CD4+CD25+ Treg in the circulation than NC (10.1±4.7 vs 5.4±2.7%). Representative flow cytometry results for one patient and one normal control are shown in Figure 1. This finding is consistent with the data reported for patients with other epithelial cancers (Woo et al, 2001; Liyanage et al, 2002). Among the cohort of 19 patients, eight had AD at the time of blood draws for this study, and 11 had NED following curative therapies (Table 1). No significant difference in the proportion of Treg was observed between these two patient cohorts, as illustrated in Figure 2. However, the percentage of Treg was significantly higher in patients with AD (P<0.0008) or NED (P<0.04) than that in NC.

Figure 1.

Enrichment in CD4+CD25+ Treg in PBMC of a patient with SCCHN relative to a normal control. Flow cytometry was performed as described in Materials and Methods. The gate was set to acquire bright CD4+CD25+ T cells. Isotype controls were used to set the cut-off for CD25+ vs CD25− cells.

Figure 2.

Frequencies of CD4+CD25+ Treg in the circulation of patients with SCCHN and NC. The patients with AD at the time of phlebotomy were not different from those with NED (P>0.2). However, the NED and AD patient cohorts were significantly different from NC (P<0.04 and P<0.0008, respectively).

Although we gated on CD4+CD25+high T cells, which is considered to be the phenotype of Treg, it was necessary to confirm their identity through expression of Foxp3 or GITR markers (Ramsdell, 2003; Ronchetti et al, 2004). To this end, we developed a flow-cytometry-based method with commercially available Abs to measure expression of these markers on CD4+CD25high T cells. In five patients with SCCHN, PBMC were found to contain an average of 7±1.5% of CD4+CD25+ T cells, 5±1.0% of CD4+CD25+ GITR+ T cells and 6.0±1.3% of CD4+CD25+Foxp3+ T cells (Table 2). These data confirm that the large majority of CD4+CD25high T cells express Foxp3 or GITR, the markers associated with Tregs.

Table 2. Percentages of Treg in PBMC of selected patients with SCCHN by expression of Foxp3 or GITR.

| Patient | CD4+CD25high (%) | CD4+CD25highGITR+ (%) | CD4+CD25highFoxp3+ (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | 9a | 4a | 6b |

| 2. | 5 | 5 | 5 |

| 3. | 8.5 | 5 | 7.5 |

| 4. | 6.5 | 3 | 6 |

| 5. | 7.0 | 5 | 5 |

| Mean±s.d. | 7.0±1.5 | 5.0±1.0 | 6.0±1.3 |

The percentages of Treg were determined upon backgating on CD3+CD4+CD25high cells following staining from surface markers, as described in Materials and Methods.

The percentages of Foxp3+ cells were determined as indicated above but following cell permeabilisation and intracytoplasma staining.

SCCHN=squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck; GITR=glucocorticord-induced TNF receptor; PBMC=peripheral mononuclear cells.

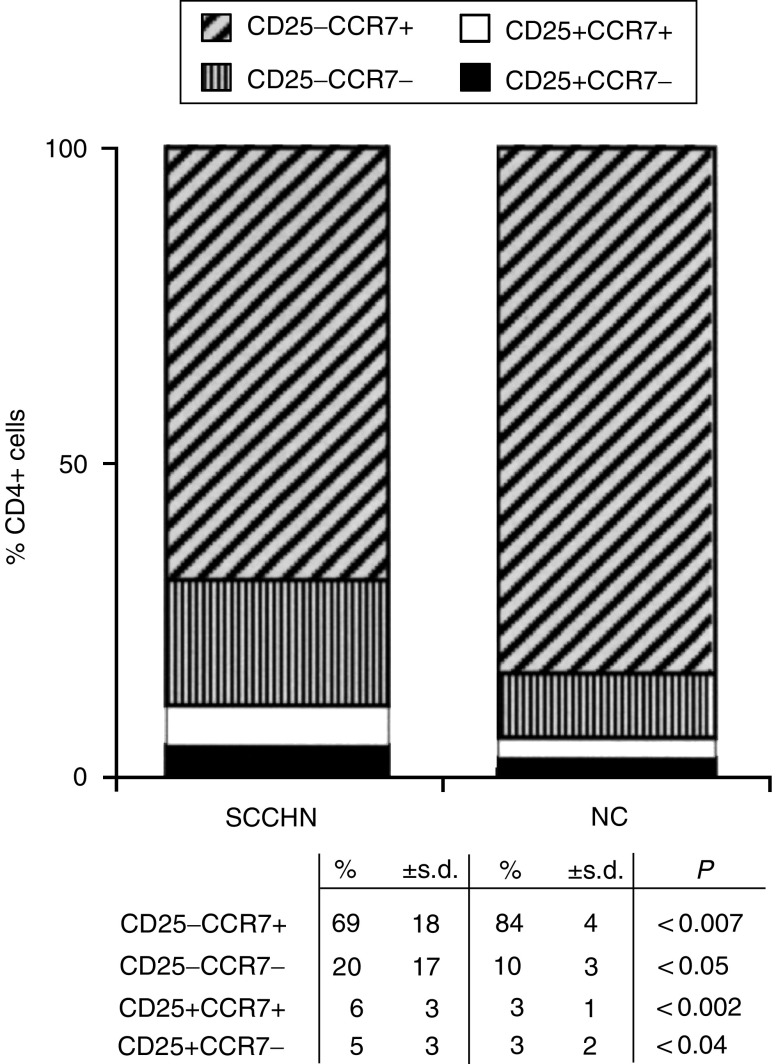

Expression of CCR7 on CD4+ T-cell subsets

Expression of the chemokine receptor CCR7 on the surface of lymphocytes is associated with the acquisition of a migratory phenotype (Sallusto et al, 1999; Campbell et al, 2001). Thus, mature CD4+ T cells expressing CCR7 are able to migrate to secondary lymphoid organs, while those lacking CCR7 are effector cells. We, therefore, studied expression of this receptor on CD4+ T cells of patients and NC, with special attention focused on the subset of Treg. The expectation was that the percent of CD4+CD25+CCR7+ cells would be lower in patients than NC, based on our report documenting an enrichment in Treg at tumour sites and tumour-involved lymph nodes relative to the peripheral circulation (Albers et al, 2004). Instead, as shown in Figure 3, the percentages of both CCR7+ and CCR7− Treg were significantly increased (P<0.002 and P<0.04) in the circulation of patients vs NC. Conversely, among non-Treg CD25−CD4+ cells, CCR7+ cells were significantly lower in patients than NC (P<0.007), and significant expansion of the CCR7− subset was evident (Figure 3). These expanded CCR7− cells are presumably terminally differentiated effector T cells (Sallusto et al, 1999). The significant shifts observed in the content of CCR7− and CCR7+ cells among the CD4+ subsets of lymphocytes in patients with SCCHN are suggestive of their distinct distribution between blood vs tissues and perhaps of differences in the activation state or turnover rate among functionally distinct subsets of lymphocytes.

Figure 3.

Altered distribution within the CD4+ T-cell subset of cells expressing CD25 and CCR7 markers in patients with SCCHN relative to NC. Note a significant decrease in CD4+CD25−CCR7+ and an enrichment in CD4+CD25−CCR7−, CD4+CD25+CCR7+ and CD4+CD25+CCR7− T cells in the circulation of patients with SCCHN relative to NC.

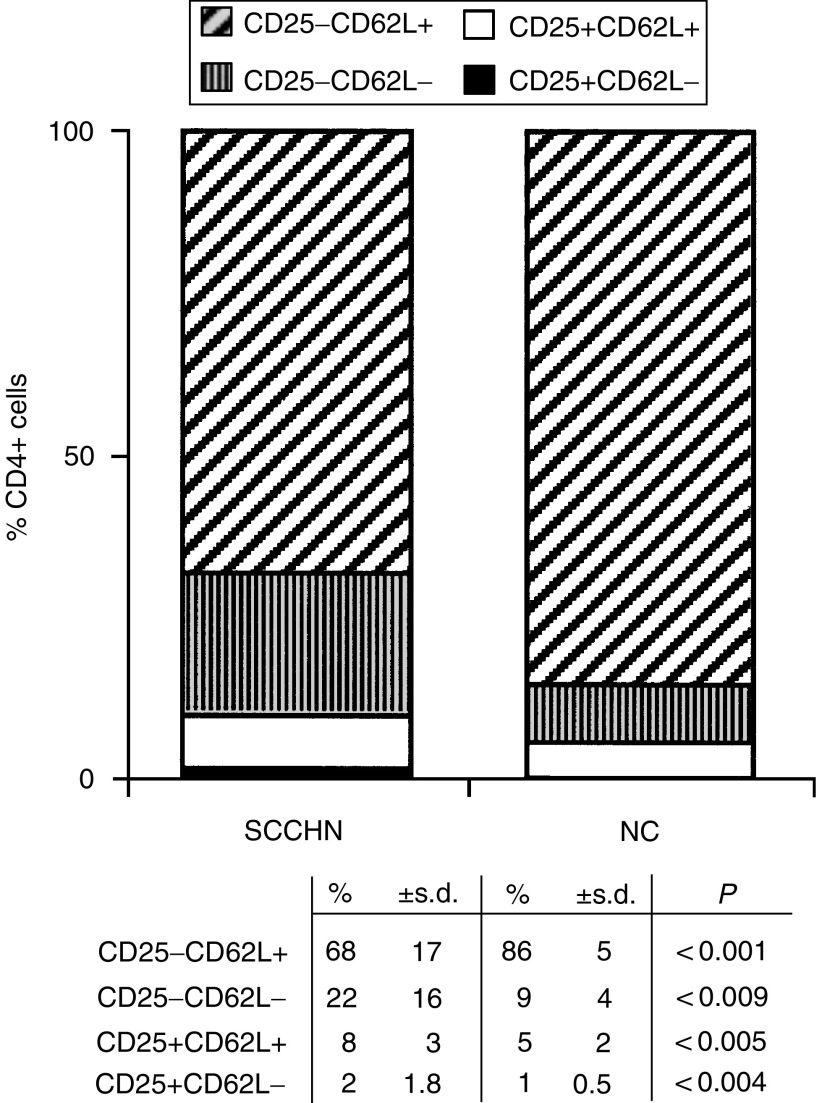

Expression of CD62L on CD4+ T-cell subsets

Like CD27 antigen, L-selectin (CD62L) expression is lost on mature, more differentiated T cells, which are responsible for helper/suppressor functions performed by CD4+ T cells. For this reason, we expected to find an increased percentage of CD4+ T cells with the CD62L− phenotype in the peripheral circulation of patients with SCCHN. As seen in Figure 4, this indeed was the case, and the expansion of CD62L− non-Treg CD4+ T in patients with SCCHN was accompanied by a significant concomitant decrease in the percent of CD4+CD25−CD62L+ cells. In contrast, among CD25+CD4+ Treg, enrichment in CD62L+ cells (P<0.005 relative to NC) exceeded that of CD62L− cells. These observations imply that Treg in the circulation of patients might be at a different maturation or activation stage than their normal counterparts. Further, the proportion of CD4+CD25− T cells that are CD62L+, that is, belong to the naive pool, is decreased in the patients with a concomitant enrichment in effector CD4+ T cells.

Figure 4.

Changes in the distribution within the CD4+ T-cell subset of cells expressing CD25 and CD62L markers. Note a significant decrease in CD4+CD25−CD62L+ and an enrichment in CD4+CD25−CD62L−, CD4+CD25+CD62L+ and CD4+CD25+CD62L− T cells in the circulation of patients relative to NC.

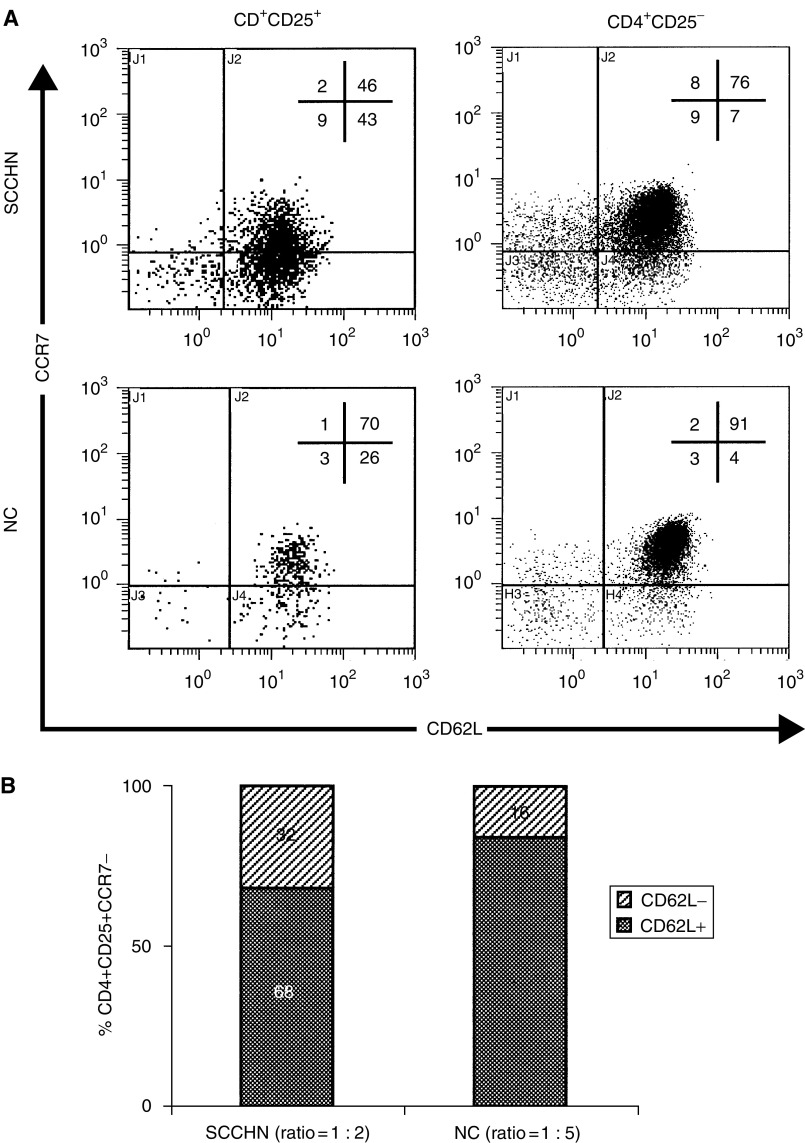

Concomitant expression of CCR7 and CD62L on Treg

Treg in patients with SCCHN contained a higher proportion of CCR7− and CD62L− cells than NC (Figures 3 and 4). A loss of CCR7 and/or CD62L markers accompanies maturation, activation or terminal differentiation of T cells (Sallusto et al, 1999; Campbell et al, 2001). We were, therefore, especially interested in a concomitant loss of expression of both these markers on Treg in the peripheral circulation of patients vs controls. Figure 5A is an example of the four-colour flow cytometry analysis performed with cells of a representative patient and a normal control. It shows that the percentage of Treg is higher in the patient than in NC and that substantially more Treg are CCR7−CD62L+ in the patient (43%) vs NC (26%). Concomitantly, the patient has fewer Treg that are CCR7+CD62L+ than NC. Thus, T cells with the CCR7−CD62L+ phenotype are the major Treg subset in patients with SCCHN. To further focus on this subset, we next examined CD62L expression on CD4+CD25+CCR7− cells in patients and NC. As shown in Figure 5B, a significant difference (P<0.03) was observed in the ratio of double negative (CCR7−CD62L−)/(CCR7−CD62L+) Treg between the patients (1 : 2) and NC (1 : 5).

Figure 5.

In (A), multicolour flow cytometry of PBMC obtained from a representative patient with SCCHN shows an increased proportion of CCR7−CD62L+ Treg relative to non-Treg CD4+CD25− cells and to NC. In (B), expansion of CD62L− T cells within the subset of CCR7-CD25+CD4+ Treg in patients with SCCHN relative to NC. The gate was set on CD4+ T cells and subsets of CD25+CCR7−CD62L− vs CD25+CCR7−CD62L+ were quantitated by four-colour flow cytometry.

In aggregate, these data are consistent with the conclusion that among Treg those with CCR7−CD62L+ and CCR7−CD62L− phenotypes are enriched in the circulation of patients with SCCHN relative to NC. This finding implies that more Treg in the circulation of patients with SCCHN than in NC are terminally differentiated and are undergoing rapid maturation and turnover.

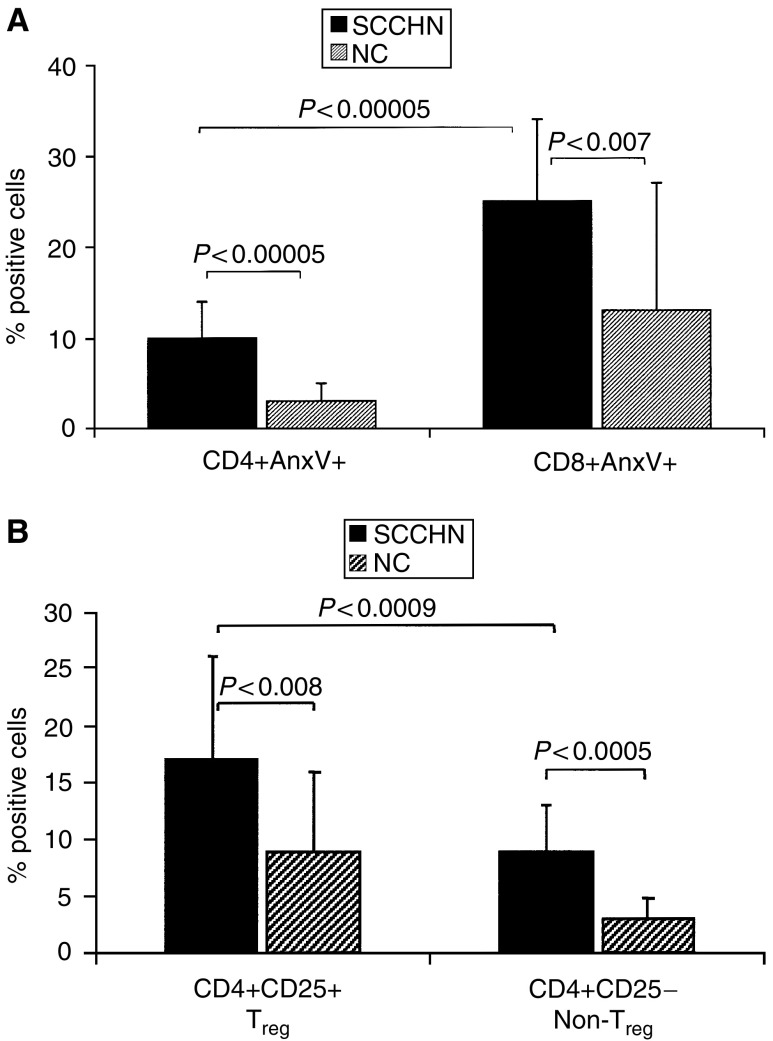

Annexin V binding to the subsets of CD4+ T cells

We have previously reported a decrease in absolute CD4+ T-cell counts in patients with SCCHN relative to age-matched NC (Kuss et al, 2004a). In the cohort of patients studied here, the mean absolute CD4+ T-cell count was 610±350 mm−3, which is significantly lower than the normal mean count of 1005±360 mm3 (Kuss et al, 2004a). It was, therefore, important to determine whether the low absolute counts of circulating CD4+ T cells could be explained by their apoptosis. To this end, Annexin V (Anx V) binding to CD8+ and CD4+ circulating T cells was evaluated by flow cytometry. In agreement with previously published results (Hoffmann et al, 2002), we observed significantly lower percentage of Anx V+CD4+ than CD8+ T cells in SCCHN patients and in NC (Figure 6A). Although Annexin binding to CD4+ T cells was significantly higher (P<0.00005) in patients than in NC (Figure 6A), the overall proportion of CD4+ T cells undergoing apoptosis was low, not exceeding 10% in the patients’ circulation.

Figure 6.

Annexin V (Anx V) binding to T cells. In (A), binding of Anx V to CD4+ and CD8+ T-cell subsets in patients with SCCHN and in NC. In (B), Anx V binding to Treg (CD4+CD25+) vs non-Treg (CD4+CD25−) T cells in patients with SCCHN and NC.

We next examined Anx V binding to the CD4+ T-cell subsets, including CD4+CD25+ and CD4+CD25− cells, to determine whether Treg are more or less sensitive to apoptosis than non-Treg. As shown in Figure 6B, Anx V bound to 17.4% of Treg and 9% of non-Treg in patients with SCCHN. In NC, 8.6% of Treg vs 3% of non-Treg bound Anx V. Anx V binding was significantly higher among Treg than non-Treg in the circulation of patients as well as NC (P<0.0009). This observation suggests that Treg are more rapidly cleared from the peripheral circulation than other CD4+ cells, perhaps as a result of their activation and migration to tissues to be utilised in regulatory activities. This rapid turnover of Treg relative to non-Treg among CD4+ T cells might be a manifestation of activation induced cell death (AICD).

Expression of ζ in Treg of patients with SCCHN

Expression of ζ chain in CD3+ T cells or their subsets is considered to be a measure of their functional status, as it determines the ability of T cells to signal upon TCR engagement (Whiteside, 2004). Using flow cytometry, we initially determined that CD8+ T cells in our cohort of patients with SCCHN had lower expression of ζ (log MFI=2.8±0.6) than CD4+ T cells (log MFI=3.4±0.7) as shown in Table 3. Although not statistically significant, this difference in the MFI was consistent with higher levels of Anx V binding to CD8+ T cells, as indicated above (Figure 6A). Among CD4+ T cells, no difference was observed in MFI for ζ expression between Treg and non-Treg (Table 3). However, consistent with a higher percentage of Treg in the peripheral circulation of SCCHN patients, ζ expression was found to be lower in all T-cell subsets (CD4+, CD8+, non-Treg) in these patients as compared to NC (Table 3). Thus, we hypothesise that Treg, which are more numerous in patients than in NC, are responsible for downregulation of TCR-mediated signalling in CD8+ and non-Treg CD4+ T cells.

Table 3. Expression of the TCR-ζ chain in T-cell subsets of patients with SCCHN and normal controlsa.

| CD4+CD25+ | CD4+CD25− | CD8+ | CD4+ | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TCR-ζ chain expression (log MFI) | ||||

| NC | 3.7±1.7 | 4.2±1.8 | 3.5±1.5 | 4.3±1.9 |

| SCCHN | 3.2±0.7 | 3.4±0.7 | 2.8±0.6 | 3.4±0.7 |

Expression of ζ was measured in the various T-cell subsets by flow cytometry as described in Materials and Methods. The data are means±s.d.

DISCUSSION

The Treg subset of CD4+ lymphocytes (CD4+CD25high cells) has assumed a considerable importance within the immunoregulatory network both in health and disease. These cells exert suppressive activity upon CD8+ effector and CD4+ helper T cells, and their effects appear to be dose dependent, cell-contact dependent, cytokine independent and antigen-nonspecific (Shevach, 2000; Dieckmann et al, 2001; Jonuleit et al, 2001; Ng et al, 2001; Taams et al, 2001;). However, more recent studies suggest that subpopulations of Treg endowed with different regulatory functions, including suppression of TAA-specific immune responses, exist in the circulation and/or tissues of patients with cancer (Woo et al, 2002; Shevach, 2004). Given the emerging heterogeneity of this cell population, it is important to consider how subsets of CD4+CD25+ cells relate to other helper T cells and to disease in individuals with cancer.

The percentage and absolute numbers of CD4+CD25+ T cells were reported to be increased in the peripheral circulation of patients with various malignancies (Woo et al, 2001; Liyanage et al, 2002). In patients with SCCHN, we have recently described a significant enrichment in CD4+CD25+ T cells in the peripheral blood and particularly among tumour-infiltrating lymphocytes (Albers et al, 2004). However, it now appears that Treg are a heterogenous population within CD4+ T cells, and that a subset of CD4+CD25+ T cells could be subdivided into different functional subsets based on expression of novel markers such as GITR, Foxp3 or neurophilin-1 (Cosmi et al, 2003; Ramsdell, 2003; Bruder et al, 2004; Ronchetti et al, 2004). Further, a subset of these cells could represent activated CD4 cells expressing the CD25+ receptor. Taking advantage of newly available Abs to GITR and Foxp3, we performed multiparameter flow cytometry to demonstrate that most CD4+CD25high T cells in the circulation of patients with HNC express Foxp3 or glucocorticord-induced TNF receptor (GITR). While this analysis was performed in only a small subset of our patients, it offers support for the phenotypic analysis of Treg subsets presented here.

The present study confirmed the enrichment in Treg among PBMC of HNC patients and offered us an opportunity to determine whether patients with AD had more circulating CD4+CD25+ T cells than those with NED. Surprisingly, both cohorts had a higher frequency of Treg than NC, and patients presumably cured of their disease following therapy were not different from those with tumours in respect to the proportions of Treg in the periphery. This observation supports our hypothesis that lymphocyte homeostasis disrupted by the presence of tumour fails to normalise following successful therapy. Immune abnormalities, including depressed absolute lymphocyte counts (Kuss et al, 2004a), elevated percentages of CD8+ cells undergoing early apoptosis (Hoffmann et al, 2002), and signalling defects (Kuss et al, 2003), persist for weeks or years after curative therapies in patients with NED. It appears that the enrichment in circulating Treg is also a persistent immune alteration that does not normalise following therapy. Nevertheless, it is apparent from the data (Figure 2) that as a group, SCCHN patients with AD differ most significantly from NC in the percentage of circulating CD4+CD25+ Treg.

The maturation status of Treg and their ability to home to lymph nodes are attributes that determine their biologic activity. We have previously shown that the majority of CD4+ T cells in the circulation of patients with SCCHN have a memory phenotype (Kuss et al, 2003). Thus, it was not unexpected to find that CD4+ T cells in patients with SCCHN were characterised by the loss of CCR7 and L-selectin surface molecules, which are functionally associated with cell migration into tissues and serve as phenotypic markers for distinct stages of lymphocyte differentiation, respectively. The implication of this finding is that in patients, CCR7+ and L-selectin+ CD4+ T cells tend to localise to tissues. We have previously reported a significant and sometimes striking enrichment in CD4+CD25+ T cells among tumour-infiltrating lymphocytes in patients with SCCHN (Albers et al, 2004), and thus we hypothesise that these cells may preferentially localise to tumour sites. If so, then Treg present in the circulation of SCCHN patients might be a mix of less mature (CCR7+CD62L+) lymphocytes being recruited from the naïve lymphocyte pool and of activated or terminally differentiated Treg, which have lost either CCR7 or CCR7 and CD62L markers. In fact, subsets of CCR7− and CD62L− Treg are expanded in the circulation of SCCHN patients relative to NC. In addition, the ratio of more differentiated (CCR7−CD62L−) to less differentiated (CCR7−CD62L+) Treg is altered in patients vs NC, because of an increase in absolute and relative numbers of more differentiated Treg in patients with SCCHN. This shift in Treg subsets could be a result of selective migration to tissues and accumulation at the tumour site or in tumour involved lymph nodes (Albers et al, 2004). Alternatively, it implies that activated Treg in the patients’ circulation undergo a rapid turnover. The observed increased binding of Anx V by Treg is consistent with this hypothesis and with previous reports indicating that CD4+CD25+ T cells are more susceptible to apoptosis than other CD4+ T cells (Salmon et al, 1994; Akbar et al, 1996; Taams et al, 2001). Such rapid turnover of Treg in patients with SCCHN and other cancers (i.e., entry from the naïve pool, maturation and migration into tissues) explains their enrichment in lymphoid and tumour tissues, and the phenotype of Treg remaining in the circulation. Based on the principle that lymphocyte activation is accompanied by their migration into tissues and/or AICD, reconstitution of the lymphocyte pool from naïve precursors must be quite efficient. However, even this rapid replacement does not seem to correct absolute CD4+ T lymphocyte count in patients with SCCHN, which ranged from 120 to 1227 mm−3, with a mean of 610±350 (s.d.) mm−3 in our patient cohort, and was significantly lower from the normal mean of 1005±360 mm−3 (P<0.001).

The expansion of Treg in the circulation and tissues of patients with cancer suggests that these cells downregulate antitumour responses, guarding from overly vigorous responses to self-antigens. Functional evaluations of Treg require their isolation and titration into functionally active tumour-specific T cells. The latter are not easily available, in humans, and are particularly difficult to generate in patients with SCCHN, where few immunogenic tumour-specific epitopes are available. For this reason, we resorted to an alternative approach dependent on the analysis of ζ expression, which is a signalling component of TCR in CD4+ and CD8+ T-cell subsets. The rationale for measurements of ζ expression was based on our previous data linking T-cell dysfunction in patients with SCCHN with the absence or low expression of the ζ chain (Kuss et al, 1999; Whiteside, 2004). In the presence of Treg, which presumably downregulate functions of other T cells, the level of ζ expression in these T cells is expected to be low, thus providing some indication about activity of Treg. It was interesting to observe that in patients with SCCHN, various circulating T-cell subsets had lower expression of ζ, as compared to their counterparts in NC. This observation is consistent with previous reports from our laboratory (Kuss et al, 1999). It suggests that signalling, and therefore effector or helper functions of T cells obtained from the circulation of patients with SCCHN are compromised in signalling via TCR, possibly because of the presence of Treg.

Finally, it has to be conceded that further analysis of the functional potential of Treg will be necessary to elucidate their impact on disease progression. The current study, performed largely by using multicolour flow cytometry with a small number of blood samples obtained from patients with SCCHN is obviously limited by the availability of cells. Nevertheless, it illustrates the importance of Treg in defining the immune profile of patients with cancer and emphasises the role of these cells in downregulating functions of other T-cell subsets.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported in part by NIH Grants PO-1 DE12321 (TLW), P60-DE13059 (ENM) and RO-1 DE13918 (TLW).

References

- Akbar AN, Borthwick NJ, Wickremasinghe RG, Panayoitidis P, Pilling D, Bofill M, Krajewski S, Reed JC, Salmon M (1996) Interleukin-2 receptor common gamma-chain signaling cytokines regulate activated T cell apoptosis in response to growth factor withdrawal: selective induction of anti-apoptotic (bcl-2, bcl-xL) but not pro-apoptotic (bax, bcl-xS) gene expression. Eur J Immunol 26: 294–299 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albers AE, Kim GG, Ferris RL, DeLeo AB, Whiteside TL (2004) Immune responses to p53 in patients with cancer: enrichment in tetramer+ p53 peptide-specific T cells and regulatory CD4+CD25+ cells at tumor sites. Cancer Immunol Immunother (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Bauernhofer T, Kuss I, Henderson B, Baum AS, Whiteside TL (2003) Preferential apoptosis of CD56dim natural killer cell subset in patients with cancer. Eur J Immunol 33: 119–124 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruder D, Probst-Kepper M, Westendorf AM, Geffers R, Beissert S, Loser K, von Boehmer H, Buer J, Hansen W (2004) Neuropilin-1: a surface marker of regulatory T cells. Eur J Immunol 34: 623–630 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell JJ, Murphy KE, Kunkel EJ, Brightling CE, Soler D, Shen Z, Boisvert J, Greenberg HB, Vierra MA, Goodman SB, Genovese MC, Wardlaw AJ, Butcher EC, Wu L (2001) CCR7 expression and memory T cell diversity in humans. J Immunol 166: 877–884 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cosmi L, Liotta F, Lazzeri E, Francalanci M, Angeli R, Mazzinghi B, Santarlasci V, Manetti R, Vanini V, Romagnani P, Maggi E, Romagnani S, Annunziato F (2003) Human CD8+CD25+ thymocytes share phenotypic and functional features with CD4+CD25+ regulatory thymocytes. Blood 102: 4107–4114 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dieckmann D, Plottner H, Berchtold S, Berger T, Schuler G (2001) Ex vivo isolation and characterization of CD4+CD25+ T cells with regulatory properties from human blood. J Exp Med 193: 1303–1310 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffmann TK, Dworacki G, Meidenbauer N, Gooding W, Johnson JT, Whiteside TL (2002) Spontaneous apoptosis of circulating T lymphocytes in patients with head and neck cancer and its clinical importance. Clin Cancer Res 8: 2553–2562 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jonuleit H, Schmitt E, Stassen M, Tuettenberg A, Knop J, Enk AH (2001) Identification and functional characterization of human CD4+CD25+ T cells with regulatory properties isolated from peripheral blood. J Exp Med 193: 1285–1294 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuss I, Donnenberg A, Gooding W, Whiteside TL (2003) Effector CD8+CD45RO−CD27− T cells have signaling defects in patients with head and neck cancer. Br J Cancer 88: 223–230 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuss I, Hathaway B, Ferris RL, Gooding W, Whiteside TL (2004a) Decreased absolute counts of T lymphocyte subsets and their relation to disease in squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck. Clin Cancer Res 10: 3755–3762 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuss I, Saito T, Johnson JT, Whiteside TL (1999) Clinical significance of decreased ζ chain expression in peripheral blood lymphocytes of patients with head and neck cancer. Clin Cancer Res 5: 329–334 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuss I, Schaefer C, Godfrey TE, Ferris RL, Harris JM, Gooding W, Whiteside TL (2004b) Recent thymic emigrants and subsets of naïve and memory T cells in the circulation of patients with head and neck cancer. Clin Immunol (in press) [DOI] [PubMed]

- Liyanage UK, Moore TT, Joo HG, Tanaka Y, Herrmann V, Doherty G, Drebin JA, Strasberg SM, Eberlein TJ, Goedegebuure PS, Linehan DC (2002) Prevalence of regulatory T cells is increased in peripheral blood and tumor microenvironment of patients with pancreas or breast adenocarcinoma. J Immunol 169: 2756–2761 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ng WF, Duggan PJ, Ponchel F, Matarese G, Lombardi G, Edwards AD, Isaacs JD, Lechler RI (2001) Human CD4+CD25+ cells: a naturally occurring population of regulatory T cells. Blood 98: 2736–2744 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramsdell F (2003) Foxp3 and natural regulatory T cells: key to a cell lineage? Immunity 19: 165–168 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reichert TE, Rabinowich H, Johnson JT, Whiteside TL (1998) Human immune cells in the tumor microenvironment: mechanisms responsible for signaling and functional defects. J Immunother 21: 295–306 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reichert TE, Strauss L, Wagner EM, Gooding W, Whiteside TL (2002) Signaling abnormalities and reduced proliferation of circulating and tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes in patients with oral carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res 8: 3137–3145 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ronchetti S, Zollo O, Bruscoll S, Agostini M, Bianchini R, Nocentini G, Ayroldi E, Riccardi C (2004) GITR, a member of the TNF receptor superfamily, is costimulatory to mouse T lymphocyte subpopulations. Eur J Immunol 34: 613–622 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakaguchi S, Sakaguchi N, Shimizu J, Yamazaki S, Sakihama T, Itoh M, Kuniyasu Y, Normura T, Toda M, Takahashi T (2001) Immunologic tolerance maintained by CD25+CD4+ regulatory T cells: their common role in controlling autoimmunity, tumor immunity, and transplantation tolerance. Immunol Rev 182: 18–32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sallusto F, Lenig D, Forster R, Lipp M, Lanzavecchia A (1999) Two subsets of memory T lymphocytes with distinct homing potentials and effector functions. Nature 401: 708–712 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salmon M, Pilling D, Borthwick NJ, Viner N, Janossy G, Bacon PA, Akbar AN (1994) The progressive differentiation of primed T cells is associated with an increasing susceptibility to apoptosis. Eur J Immunol 24: 892–899 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shevach EM (2000) Regulatory T cells in autoimmunity. Annu Rev Immunol 18: 423–449 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shevach EM (2004) Fatal attraction: tumors becon regulatory T cells. Nat Med 10: 900–901 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimizu J, Yamazaki S, Sakaguchi S (1999) Induction of tumor immunity by removing CD25+CD4+ T cells: a common basis between tumor immunity and autoimmunity. J Immunol 163: 5211–5218 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sutmuller RP, van Duivenvoorde LM, van Elsas A, Schumacher TN, Wildenberg ME, Allison JP, Toes RE, Offringa R, Melief CJ (2001) Synergism of cytotoxic T lymphocyte-associated antigen 4 blockade and depletion of CD25+ regulatory T cells in antitumor therapy reveals alternative pathways for suppression of autoreactive cytotoxic T lymphocytes responses. J Exp Med 194: 823–832 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taams LS, Smith J, Rustin MH, Salmon M, Poulter LW, Akbar AN (2001) Human anergic/suppressive CD4+CD25+ T cells: a highly differentiated and apoptosis-prone population. Eur J Immunol 31: 1122–1131 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whiteside TL (2004) Down-regulation of ζ chain expression in T cells: a biomarker of prognosis in cancer? Cancer Immunol Immunother 53: 865–876 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolf AM, Wolf D, Steurer M, Gasti G, Gunsilius E, Grubeck-loebenstein B (2003) Increase in regulatory T cells in the peripheral blood of cancer patients. Clin Cancer Res 9: 606–612 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woo EY, Chu CS, Goletz TJ, Schlienger K, Yeh H, Coukos G, Rubin SC, Kaiser LR, June CH (2001) Regulatory CD4+CD25+ T cells in tumors from patients with early-stage non-small cell lung cancer and late-stage ovarian cancer. Cancer Res 61: 4766–4772 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woo EY, Yeh H, Chu CS, Schlienger K, Carroll RG, Riley JL, Kaiser LR, June CH (2002) Cutting edge: regulatory T cells from lung cancer patients directly inhibit autologous T cell proliferation. J Immunol 168: 4272–4276 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]